Book Cover

I started researching family history a long time ago. I was driven by a desire to find out what kind of people my great-grandparents were, how they lived and what they did. When I was born, almost none of them were alive. I did catch my grandmothers, but they died early. My parents were the youngest in the family and also grew up without grandparents. My father and mother were reluctant to tell me about their parents, and probably knew little about their grandparents. That was the time.

I wanted to reconnect with my ancestors. I didn't look for heroes or personalities, I didn't want to gloss over their successes or hide their failures and mistakes, least of all to find their noble roots. What I found was more important to me. I began to see my life as a link in a chain of successive generations of people, who suddenly became dear to me. The choice of the profession, that I had always thought was random, was rather predestined. It turned out that my great-grandfather and I graduated from the same department of Moscow University, only in his time it had a different name. It turned out that my great-grandfather, grandfather and grandmother had worked as teachers all their lives, just like me. Not to mention some traits of their characters and interests in which I recognised myself.

This book tells the story of three generations of my ancestors, starting with my great-grandparents. Chronologically, the biographical sketches cover the period from the first half of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twenty-first century. I was able to find the names of my ancestors, starting from the middle of the XVII century, in some family lines.

page5

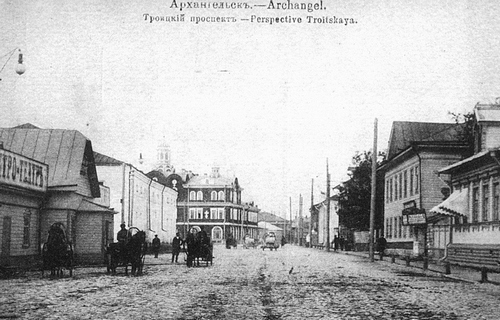

All of them are included in the genealogical tree, but it has not yet been possible to reconstruct their life history.The biographical sketches are based on information collected from documents and letters preserved in my home archives, found in various state archives in Moscow, Arkhangelsk, Vilnius, Tver, Kishinev and St. Petersburg, as well as personal memories, mine and those of relatives. In order not to overload the text with footnotes, I left only those that contain additions and explanations. Inaccuracies and mistakes are inevitable in both documents and memoirs, but I have not made anything up and in all cases stipulated my assumptions.

The most subjective essays are about the people who I have known and been associated with for most of my life. They were my parents and my mother's sisters. I couldn't resist telling you about the apartment on Glazovsky Lane where our family lived for more than 40 years and where I spent my childhood. The search for materials was fascinating and took many years intermittently. It would hardly have ended with the writing of these essays if I had not found relatives who were engaged, as I was, in family history. I am grateful to my second cousin David Kinna for setting up the site and sharing his materials with me. An invaluable find for me were the letters his grandmother Rachel received from his siblings in Moscow. The two years of correspondence between David and I served as a stimulus to keep working.

I received tremendous help and support from Olga Ivankova, my grand-niece, who shared materials collected on her behalf by researcher Alexander Vorobyov. Olga's opinion, having read the first drafts of some of my biographical sketches, was very important to me.

My niece Iryna Dadykina-Rabinovich has been engaged in family history for many years, and she shared with me her documents.

page6

The results of Irina's searches in the lineage of Slytinovskys are reflected in publications as well as in the work to commemorate the memory of martyr Konstantin Pereslavsky (Slytinov).I am grateful to my cousins Olga Demitrovich for memories about my father, my uncle Ivan Petrovich and our grandmother Glafira Ivanovna, and Lyudmila Chernyavskaya, who shared the documents and photos of my father, my uncle Ivan Vasilyevich.

Special thanks to Mikhail Gershzon, a graduate of Moscow State University, a professional in the field of genealogy, for his valuable advice and assistance in the collection of archival documents.

Thank you to my family, Nikolay, Leonid and Anna Zezin, for their support and help.

page7

The number of ancestors increases exponentially as I go further back in time: two parents, four grandparents, and eight great-grandparents. Here we will talk about only four of my father's side of the family whose lives I have been able to find out about.

On my mother's side I only know the names of my great-grandfathers - Panfil Ivanovich and Yegor. The serfs had no surnames. I managed to restore Panfil Ivanovich's genealogy from the end of the XVII century. Since neither my mother nor her sisters knew the patronymic of their grandfather Yegor, it was impossible to find the names of his ancestors. Unfortunately, the names of his great-grandmothers remained unknown.

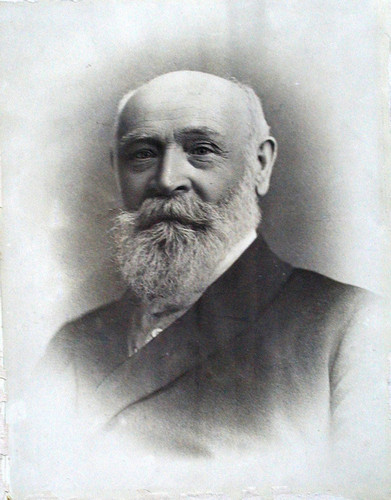

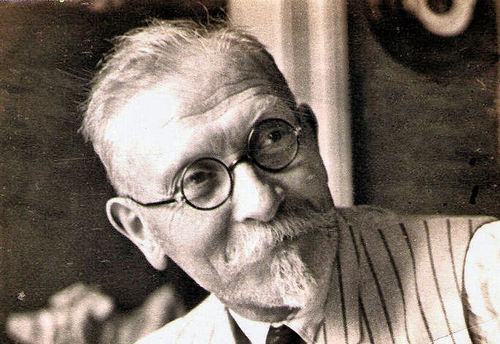

I first heard my great-grandfather's name when, as a child, I came across a booklet of religious sermons published in Kishinev in the late 19th century that I had kept in my bookcase. It was so different from the books in my parents' library that I approached my father. My father answered that Joseph Davidovich Rabinovitz was his grandfather, but did not tell me anything more about him. I later learned that Joseph Rabinowitz was a famous religious figure of his time, preaching Christianity among the Jews of Bessarabia, and that his teachings have followers in modern Russia. There is an article about him on Wikipedia, and the Danish researcher Kaj Kier-Hansen wrote a monograph about him

page8

The story I am about to tell is based on information from Kier-Hansen's book, Joseph Rabinowitz's autobiography, the Internet, and information received from newfound relatives, Olga Ivankova, Joseph's great-granddaughter, and David Kinna, his great-grandson.

Joseph Rabinovitz was born on September 23, 1837 in Rezina, a small town that was part of Orhei district, and in the middle of the 19th century had a population of about 1,000 people (now Rezina is the capital of Rezina district of the Republic of Moldova). His father David Efroimovich was the grandson of the Orhei rabbi Wolf Rabinovitz. His mother, Esther-Sara, came from a Hasidic family. Esther-Sara died early and David married again. According to the register sheets for 1848, 1854 and 1859 the family had sons Abram (1835), Yankl (1839-1897), Meer (1841), Wolf-Aizik (1848), Goshey (1850), Shabs (1852), Itzik (1857) and daughters Beila (1843) and Maryam (1854) from both marriages of the father.

page9

Joseph spent his early childhood after his mother's death in the home of his maternal grandfather, Rebbe Natan Net (a student of the Hasidic tzaddik. In his grandfather's house he received a religious education, studying the Mishnah, the Gemara, and Rashi's commentaries. In 1848, when his grandfather became old and weak, and could no longer be engaged in the upbringing of his grandson, his father took the boy to Orgeev to his mother, Grandmother Rivka, who by this time had become a widow. For the next five years Joseph continued his study under the tutelage of Joseph Kivovitch, a private teacher and follower of the Rabbi Rafael of Bershid, a Hasidic tzaddik, and studied medieval Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah). Remembering this time many years later, Joseph Davidovich wrote in his autobiography “ I found no pleasure in the amusements and activities of my young companions." Playing with his peers was hindered by his lameness due to a congenital deformity of the foot.

page10

It is unlikely that Joseph was interested in girls and making plans for a future family life. According to Hasidic tradition, his parents decided everything. In July 1853 Joseph was betrothed to fourteen-year-old Golda Goldenberg before he was sixteen. The wedding was to take place three years later. In the meantime he continued his studies. According to tradition young men did not work before marriage and for the first year after, but devoted all their time to the study of sacred books. As he grew older, so did the times. The ideas of the Jewish Enlightenment were penetrating Russia from Europe. Joseph began to read the works of Moses Mendelssohn and modern Jewish literature. The circle of his interests extended beyond Hasidism. Joseph's views were greatly influenced by his friendship with Girsh (Ikhil-Tzvi) Gershenzon, who planted doubts about the absolute truthfulness of Hasidic interpretations of Holy Scripture. Gershenzon gave Joseph a Hebrew translation of the New Testament, saying: "Perhaps this was the real Messiah about whom Moses and the prophets prophesied.

page11

In December 1854 Joseph married Golda. According to tradition, for the first 18 months after the wedding the young family was to live with the wife's parents. On September 13, 1856 they had their first child, Haim-Volke, and in 1857 their daughter Sarah. A year and a half after the wedding Joseph established a small shop in Orhei, and rented a house for the family, using the 800 silver roubles he had received as a dowry. Joseph frequently saw Gershenzon, who, following his marriage to Joseph's sister, became not only a friend but also a relative.

In 1859 a misfortune befell the young family. A fire broke out in the town and everything was burned - the shop, the house, the books.

"The next ten years", Joseph wrote in his autobiography, "were filled with bitter suffering and anxiety. I had to find a livelihood". A young man immersed in philosophical and religious books, with no practical training, how was he to make a living? He began diligently studying the Russian language and the law in order to provide legal advice to Orhei Jews, most of whom spoke only Yiddish.

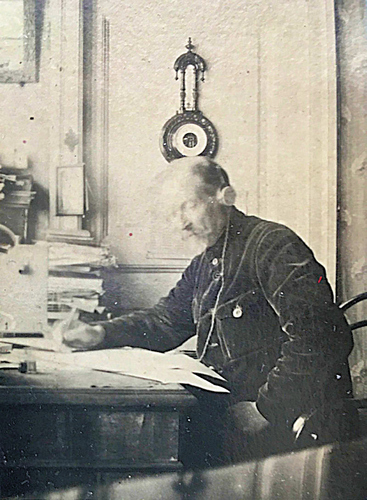

Joseph was a gifted man with a thirst for knowledge. Without having a degree in law, he obtained a formal license to practice law and became a respected lawyer in town and a well-known journalist in Jewish circles. He was often addressed as "doctor" or "rabbi" although there was no formal reason to do so. His correspondence began to appear in the Odessa paper Ha-Melitz.

page12

Joseph received the title of chartered solicitor (attorney). It is not clear how he managed to do it. The prerequisite for obtaining the rank was a higher legal education, which Joseph did not have, and service in the judicial office. He had only a private practice.

Having accumulated the necessary funds, in 1866 Joseph Rabinowitz opened a wholesale trade of tea and sugar in Orhei county. Three years later he was elected to the county council and became the only Jew on it. The family was growing. Rebecca was born in 1868, Rachel in 1869 and Tikva in 1870.

Joseph opened a community elementary school in Orhei, teaching Talmud and Torah, Hebrew and Russian, and became a member of the Russian language "Society for the Dissemination of Education among the Jews in Russia” He believed that education and enlightenment would make Jews equal members of society and that European countries would see that "their Jewish brother is also a man." The Pale of Settlement was abolished for merchants of the First Guild and university graduates. Craftsmen and artisans are allowed to register as tradesmen and to reside outside the Pale of Settlement. Jews received a right to open printing houses for Jewish books, and to acquire land and properties belonging to landlords. The reform of public education in 1864 opened access to secondary education for all children regardless of rank and religion.

The liberal reforms, however, affected only a small part of the Jewish population. The bulk continued to live in their closed world, in poverty, ignorance and fear of pogroms. The Odessa pogrom of 1871, which continued for

page13

three days with the connivance of the police, made a strong impression on Joseph. He saw that "education and enlightenment could not protect the Jews from the fury of their neighbors" or save them from contempt, reproach and threats. The work in the county council was also disappointing.Joseph sold his business and property in Orhei, and on November 9, 1871 he moved with his entire family to Kishinev. Settlement in the new place was overshadowed by family tragedy. A cholera epidemic which broke out in 1872 claimed the life of the youngest daughter, two year old Tikva. The family moved into the new house which was constructed in 1873 without her. Joyous events soon followed: David was born in 1874 and Nathan in 1876.

Kishinev opened wide opportunities for an active and enterprising person. In 1873, after the Bessarabian region was transformed into a province, Kishinev became a provincial city. The city grew rapidly. By the end of the century, the population reached 108.5 thousand people, 46 per cent of whom were Jews, 27 per cent Russians and 17 per cent Moldovans. But progress hardly touched most of the townspeople. Samuel Wilkinson, who visited the Rabinowitz family several times, called the Jewish quarter of Kishinev "an Asian city." It was, he said, a veritable ghetto that had not been reached by any of the new trends already evident in the city.

On moving to the capital of Bessarabia, Joseph had intended to continue the wholesale trade in tea and sugar, but quickly abandoned the venture. He sensed that his vocation lay elsewhere. He decided to become a Counsellor and Advocate of the Jews. He had a large circle of friends and acquaintances who would go to him for legal advice.

page14

He also began giving private lessons in Hebrew and Russian. Zederbaum, publisher of Ha-Melitz, which had moved to St. Petersburg after the Jewish pogrom in Odessa, invited him to become the permanent Kishinev correspondent. As a correspondent, Joseph saw his task as drawing public attention to the plight of the Jews. However, this did not seem to him sufficient as he strove for practical work. In his opinion, the Jews should cultivate what he saw as the most profitable and useful occupations. Rabinowitz published articles in the press on the improvement of the rabbinate and Jewish education, and called for the general engagement of Jews from an early age in agriculture. Leading by example, he himself began to work daily in his garden, engaging his young sons David and Nathan.

In 1878, together with Dr. Levinzon, he organized. The idea of involving the Jewish population in farming was not new. The tsarist government attempted to do this back in the early 19th century by introducing privileges for Jews who had joined the peasant estate. The government was not very successful. By the mid-nineteenth century only 3 per cent of the Jewish population of the Russian Empire worked as farmers. In Bessarabskaya Province the situation was slightly better - Jews-agriculturalists amounted to about 16%.

The government's policy on the Jewish question changed dramatically in 1881 after the assassination of Alexander II. Rumors of Jewish involvement in the assassination of the tsar provoked a wave of Jewish pogroms, which lasted about a year. Fortunately, there were no victims in Kishinev. In May 1881 the Government introduced Temporary Regulations, which severely restricted the rights of the Jewish population. Jews were forbidden to settle in the countryside, except in agricultural colonies,

page15

to acquire immovable property outside towns and cities and to rent land. The pogroms and the denial of rights gave rise to the spread of the idea of Zionism and the emigration of Jews to Palestine.

In November 1881 Joseph attempted to realize his plan to introduce Jews to agriculture. He petitioned the Governor of Bessarabia together with his brothers Yankel and Meir for permission to establish a Jewish agricultural colony. Having received a refusal in February 1882, he resolved to find a place for the colony in his historical homeland. Joseph went to Palestine.

He arrived in Jaffa, a port of entry for Jewish immigrants from many countries, and was deeply disillusioned. The city seemed to him the poorest, most squalid place he had ever seen. An émigré committee, consisting of only two people, was not to be trusted. In their efforts to bring immigrants to the Promised Land, Rabinowitz saw only self-interest. In Jerusalem, he witnessed the contemptuous treatment of Jews by Muslims and the mockery and oppression of worshippers at the Wailing Wall. His tales of Palestine upon his return to Kishinev caused some of his fellow countrymen to reject emigration, or to opt for America. But the main result was something else.

page16

The trip to Palestine was a turning point in the life of Joseph Rabinowitz. The transformation happened instantly. Joseph said that while standing on the Mount of Olives, he suddenly realized that the Messiah, about whom Moses and the prophets had written, was Jesus and that all the suffering of the Jews stemmed from the fact that they denied it. As he descended the mountain, he felt his soul being reborn to a new life. He returned to Kishinev a changed man. "The road to the Promised Land for the Jews does not lie across the Mediterranean Sea, but across the Jordan", he told his relatives.

How and why was there such a rapid change in the views of a man who was brought up in a Hasidic family and who studied Jewish literature in depth? There is no answer to this question, there is only speculation and conjecture. You can read about it in detail in Kaj Kjar-Hansen's book. For us it is more important to know how his life was after his return from Palestine.

For almost a year-and-a-half Joseph disappeared from public life and there is no reliable information about this period. The result of his secluded thoughts were thirteen theses, in which Joseph set out his views on how to improve the plight of the Jews in Russia. He wrote that neither emigration to the historical homeland nor assimilation with the native Russian population would help. The only way to salvation lies through the recognition of Jesus as the brother of all Jews. At the end of 1883

page17

the theses, written in Hebrew, were given to Rudolf Faltin, pastor of the Kishinev Lutheran community. Faltin sent them to Germany, where they were translated into German and printed. An abstract in Swedish was soon published in Sweden, followed by translations into English and French.

In March 1884 three representatives of the British Missionary Society came to Kishinev to become acquainted with the new movement. A small conference in Kishinev resulted in new publications. Discussion took place in both the Jewish and Christian press. There was a lot of interest in the ideas of Joseph Rabinowitz, but not overwhelming interest. It has been noted that Joseph misunderstood the mission of Christ, who came into the world to atone for men's sins rather than to grant Jews equal rights with other nations. Joseph later acknowledged this. He described the evolution of his ideas: "In the beginning I saw Jesus as a great man with a heart full of compassion; later as someone who wanted to bring good to my people; and finally as someone who atoned for my sins".

Joseph Rabinowitz was not the first Jew to adopt Christianity and to preserve his Jewish identity but he was the first to raise the question in public. He met with both supporters and opponents. In Russia, most Jews took a negative view of Joseph Rabinowitz's ideas. The newspaper Ha-Melitz, of which Rabinowitz was a regular correspondent for many years, characterized him as an old man who had forgotten everything he knew and lost his mind, claiming that none of the Jews except the brother of Joseph followed him. The Jewish press attributed Rabinowitz's conversion to direct bribery by the Lutheran mission.

page18

PreacherRussian authorities, both secular and spiritual, were favorably disposed toward the new religious trend. On Christmas Eve 1885, Rabinovitz received permission from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to hold public meetings. The first meeting, held at the home of Joseph's brother Ephraim Yaakov, attracted about two hundred people, Jews and Christians alike. The name of the community, suggested by Rabinowitz, "Israelites of the New Covenant," reflected the essence of the movement, which united Jews who believed that the God of Israel, through His Messiah, Christ, had given Israel a New Covenant. According to Russian law, the new community's house of prayer was called a Jewish synagogue, because Jews who believed in Christ remained Jewish. Up to the end of his life Joseph considered himself a Jew. He was convinced that a Jew who believed in Christ did not lose his national identity. An Englishman who accepted Christianity remained an Englishman, as did a German, a Frenchman or any other nationality.

However, the majority of Kishinev's Jewish population considered him a traitor. Crowds gathered around the community prayer house to express their outrage. On several occasions, the police had to be called in to shield Joseph from attacks. On one occasion in February, he was attacked by a street demonstration which threw snowballs at him as he travelled in a carriage with his daughter. There were rumours of his imminent assassination. At the same time, the number of his supporters was growing. The prayer house could not accommodate all those who wished to attend. Joseph received many letters from all over Russia and abroad.

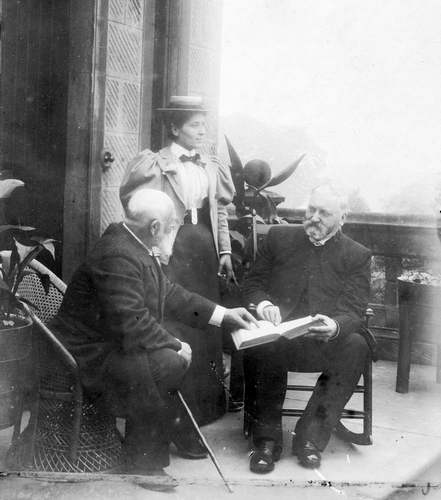

The interest of the Messianic congregations abroad in Joseph Rabinowitz's activities was mutual. Joseph, too, was eager to meet his fellow believers. In the spring of 1885 he went to Germany.

page19

This trip was financed by the most influential of the European Messianic groups, the British Mildmay Mission, whose representatives also travelled to Germany to meet Joseph. The trip proved remarkably successful. Mildmay Mission supported the Kishinev community financially. There were no conditions attached to the financing. The money went directly to Joseph Rabinovitz and he had complete freedom in his activities, both in doctrinal matters and in the practice of worship.

Joseph did not want to associate himself with any of the Christian churches, so he decided to be baptized in the Evangelical Church in Berlin. He was to be baptized by an American priest, Professor C.M. Mead, who later described in detail the events leading up to his baptism. It is customary to choose a new Christian name for the Jews when they are baptized. At first Joseph agreed to take the name "Paul", but then said that according to Russian law he could not change his name.

page20

Joseph's German friends tried to persuade him of the need for the new name, but Joseph was adamant.

It is difficult to understand his stubbornness. I doubt if there was a law in Russia forbidding a new name when a non-Christian was baptised. After all, all of Joseph's sons changed their names, Haim-Volke became Vladimir, Nathan became Peter, David became Ivan. Anyway, the Germans had to agree with Joseph when the priest showed evidence that such a baptism with the preservation of the name had already been in his practice.

There was another circumstance that could have spoiled the procedure. In the Evangelical Church, the sacrament of baptism involved the use of the Apostles' Creed. Rabinowitz had nothing against the Apostles' Creed, but he wanted to express his faith in his own words. Mead found the text written by Rabinowitz quite satisfactory and did not object. Many others, however, and in particular the pastor of the church where the rite was to be held, insisted on the Apostles' Creed. Despite Mead's pleas, Rabinowitz stood his ground. It was a matter of principle for him to be allowed to express his faith in whatever form he chose. Eventually Mead and others involved in the upcoming baptism agreed to dispense with the rite and honor Rabinowitz's wishes. This most important event in his life took place on March 24, 1885. Only a few people attended the ceremony, as it was decided to keep the news secret until Rabinovitch returned to Kishinev.

Despite his disagreement with Joseph, Pastor Meade had no hard feelings or irritation at his behaviour. On the contrary, Rabinovitch made a most favourable impression on him as a man of strong convictions and serious goals.

page21

Mead noted that Joseph was grateful for the help and support of his Christian friends, and readily accepted their advice, but was adamant when it came to subjects he knew better than his advisors.

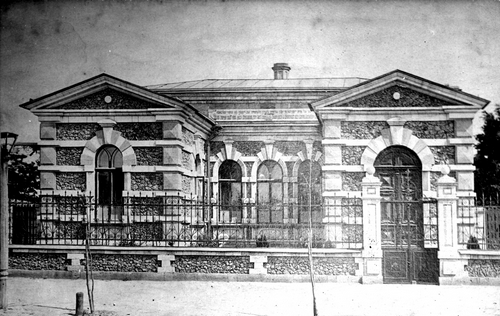

Joseph was anxious to return home and begin his work. He believed that, knowing the situation of the Jews in the South of Russia, he could find a way to convince them to abandon their prejudices and accept Christ. His plan was to found a Jewish-Christian church, different from the other Christian churches, like the Anglican, Swedish or French churches. He informed the authorities of his baptism, expecting to receive an official clergyman's certificate. However, he was refused. The Israelites of the New Covenant community established by Rabinovitz was not recognized as an independent church with the right to perform baptisms, marriages, and funerals. Nor was he recognized as a priest. This placed his followers in a ambiguous position. Regardless of which church the Israelites of the New Testament were baptized in, they were no longer considered Jewish, but had become Lutheran, Catholic or Orthodox. For this reason, Joseph himself refused to be baptized in the Kishinev Lutheran Church, and chose the Evangelical Church in Germany, which united the various Reformed streams in Christianity. This choice spoiled his relationship with the Lutheran pastor, Faltin, who supported his early steps toward Christianity, but allowed him to remain a Jew. From 1885 until the end of 1890, Joseph Rabinowitz held services at the home of his brother Ephraim Jakob. In December 1890, a new building was completed next to the house where Rabinovich's family lived, and it was named Somerville Hall. after the Scottish churchman A.N. Somerville.

page22

Somerville supported the activities of Joseph Rabinovitch and visited Kishinev in 1888, shortly before his death.

Funds for the building "Somerville Hall", were obtained from a group of Scotsmen. It looked a little like a church, became the venue for the service of the "Israelites of the New Testament ". The advent of a permanent building for Rabinowitz to preach sparked a new surge of interest in his teachings. How many people came to hear Joseph Rabinovich? The auditorium was designed for 200 people, and at first there were not enough seats, people were standing. But it wasn't always like that. The congregation did not have the means used by many other religious missions to attract people- dispensaries for poor .

page23

There was no organ and no choir. People came only to listen to the preacher, who spoke Yiddish. Many came out of curiosity, some to gather information against Rabinovich. The number of his followers cannot be judged by the number of visitors. Obviously, they were few, and their number was not growing, but shrinking. But the popularity of Joseph Rabinovich in Russia and abroad was much higher than that of other Jewish preachers. He received a large number of letters both supportive and critical. Jewish newspapers all over the world reported on him. Russian intelligentsia cared about the Jewish question, as testified by V.S. S. Sologuev, V.V. Rozanov and L.N. Tolstoy.

Joseph's activities were mainly confined within the walls of the house of prayer. He rarely visited his parishioners, but there were occasional visits. In 1888 he conducted Bible studies in his house, and in 1891 Bible reading was held on Tuesdays

page24

. Joseph planned to open a school in the community, but did not get permission from the authorities. He had a small printing press donated by Scottish brethren, through which he and his associates distributed the New Testament in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian, as well as Rabinowitz's sermons. He was assisted by one of his parishioners, R.F. Feinzilber, who from 1890 became his constant intercessor. Joseph's children also helped out. In 1894, together with his son Ivan, they visited the poor people who came to his service. Upon hearing of Rabinovitz's coming, the neighbors gathered, and Joseph prayed with them. In the same year together with his son Peter they went to Kherson, Kiev and Kremenchug to preach among the Jews. The youngest daughter Rachel and eldest son Vladimir helped the most. In 1892-93, on the recommendation of Rabinovich, Mission Mildmay hired his son-in-law Joseph Axelrood to distribute religious literature in Odessa and southwestern Russia. Axelrood's work was short-lived, and he died in 1893. According to the philosopher V. S. Solovyov, "One should not be surprised that Rabinowitz's preaching was not a great success, but that it was nevertheless a success ". Most Jews find it difficult to betray their ancestral faith and to acknowledge Christ. The attitude of the Christian world towards them - restrictions on their rights, anti-Semitism in everyday life, and pogroms - was psychologically and morally unforgivable. Those who were ready for Christian forgiveness and came to the community of "Israelites of the New Testament" faced an insoluble dilemma: they could not receive baptism with Rabinowitz, but after baptism in a Lutheran mission or any other Christian church, they had to leave the community and became parishioners of those churches.

page25

Joseph Rabinovitz's opponents accused him of being bribed by foreign Christian missions. V.S. Soloviev, who met Rabinovich many times and dedicated his work "New Testament Israel " to him, had no doubts about his perfect sincerity. Rabinovich's biographer K. Kier-Hansen also refutes accusations of Joseph's mercenary motives. Before converting to Christianity, Joseph's financial situation was much better than that of the majority of the Jewish population in Russia. His income from the practice of law allowed him to build a house with six spacious rooms in Kishinev in 1873. In 1884, when he publicly announced a change of faith, his practice was reduced. From then on, he began receiving help from abroad. The first funds came from England, from the Mildmay Mission, followed by support from Jewish missionary organizations and private sponsors from other countries. From 1887, when the London Council for Rabinowitz was formed, all money collected from organizations and individuals passed through the Council. In addition to the London Society, committees appeared in Edinburgh and Glasgow, to raise funds from private donors. The annual budget, which included maintenance costs, the money for Joseph Rabinowitz's family, paying his assistants, printing and distributing his sermons and pamphlets, amounted to about £500. After Joseph's death, the London Society used the remaining money to help his orphaned family.

page26

After converting to Christianity, Joseph traveled frequently abroad, where there were many Jewish-Christian communities. In the winter of 1886-1887, he spent a month and a half in England as a guest of the Mildmay Mission. He attended many meetings, met people and gave presentations on his work. He was not always well received. The meetings of 8 and 15 January were on the verge of a riot, so Joseph left them under police guard. From London he went to Scotland, where he addressed several meetings in Glasgow and Edinburgh. During his time in Britain, he made a most favourable impression on all Christian-Jews in contact with him. Modesty, gentleness and childlike openness mingled with energy and inner fire as he spoke of Jesus and quoted from the Gospels. A key outcome of his talks was the creation in Scotland of a committee to support Rabinowitz's work and the London Society for Rabinowitz.

On the way home, Joseph spoke in Leipzig at the Institute of Jewish Studies.

On his second trip to England and Scotland, in the autumn of 1889, Joseph did not return empty-handed. Scottish sponsors had promised to provide funds for the construction of a house of worship for the Kishinev congregation. As early as 1887 Joseph Rabinowitz purchased a parcel of land adjacent to his home in order to have it built. In May 1890, the first stone was laid and by the end of the year, Somerville Hall was completed.

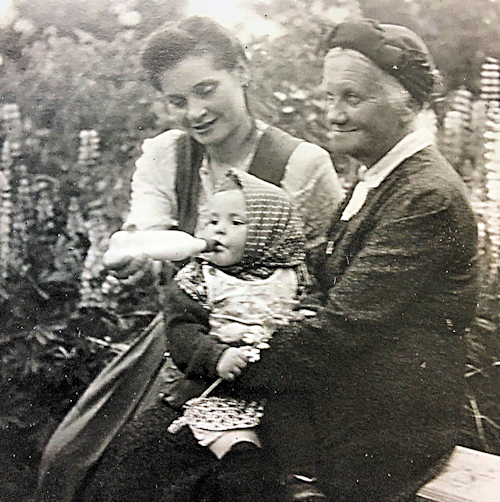

Accompanying Joseph on this journey was his youngest daughter Rachel, who stayed in Edinburgh for two years at the Deaconess School. On the way back from London, Rabinowitz stopped in Paris where he attended two meetings.

A special event for the whole family took place in October 1891, Golda was to be baptised. By this time all of Joseph and Golda's children had already been baptised, the daughters, in the Hungarian city of Budapest in 1887.

page27

Golda was baptised on 5 October 1891 by a pastor of the Free Church of Scotland, working in Budapest.

The third trip to England and Scotland, the shortest, just two weeks, took place in early 1893, when Joseph came to negotiate with the London Society. He surprised everyone by speaking for the first time without an interpreter. He had attempted to speak English before, but unsuccessfully. Now he had mastered the language well enough to read letters and speak.

In the summer of 1893, Joseph spent 35 days in the USA at the invitation of the renowned evangelist Dwight Moody and with financial support from the London Society The purpose of the trip was to pray with the Jews during the Chicago International Exposition. He also wished to see how the Jews immigrated to America. His impressions were most unfortunate.

He last went to England and Scotland in 1896 and spent about a month and a half there from May 18 to the end of June. He was accompanied by Rachel. Joseph spoke at the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland and other church meetings. On his way back, he and his daughter stopped in Berlin to see the Berlin Exhibition.

page28

Editions of the Bible in various Yiddish dialects were being prepared. Rabinowitz had to edit the text of the Bible translated into Yiddish according to the dialect spoken by the unsaved Jews. This work took several years.

On March 6, 1899 Joseph wrote of his illness, indicating that editing was nearly complete. While receiving medical treatment in Merano and later in a sanatorium in Odessa, he continued to work two hours per day but did not finish the editing. The book was only published after Joseph's death in January 1901.

In 1896, Joseph announced a project to move his work to Jerusalem to establish a school or youth work center there, free from the dominance of any of the existing Christian churches. He argued that the spread of the Messianic movement in Jerusalem would convert the Jewish nation into a Christian nation, preserving its national identity. The project found no support and was shelved. All the more so because Joseph had been given other work to do at the time. A project proposed by Joseph in 1897 to use the railroad for the spread of the Messianic movement remained unrealized. The plan was to build a special wagon to house the preacher and store religious literature, and, with permission from the authorities, travel in it through southwestern Russia, stopping on reserve tracks, distributing the Bible, and preaching to the Jewish population. The idea was not new. American Baptists had already equipped three "evangelical" trains and were about to build a fourth. The approximate budget for the construction of such a car, calculated by Joseph's eldest son Vladimir, an engineer,amounted to £540 .

page29

Rabinovitch's project was supported. Fundraising began. But the leadership of the Mildmay Mission decided to postpone it until the Bible publication was completed.

Joseph was only 60 years old. There were many plans, but as he grew older he thought more and more about death. He had a large family in his care: a wife, younger sons who were students, and three daughters, two of whom were unmarried and one was widowed. Their future had to be taken care of. On 1 December 1897 Joseph Davidovich drew up a will, which detailed how to divide the inheritance. The cash remaining after the funeral and the installation of the monument, was to be received by the female half of the family: the wife and married daughter Sara, 500 rubles each, and unmarried daughters Rebecca and Rachel, 1,000 rubles each. Thereafter, all seven heirs, including the three sons, divided the movable and immovable property in equal shares. In the event of disagreement, the heirs were to settle disputes by a vote, in which the sons each had a vote and the wife and daughters each had half a vote.

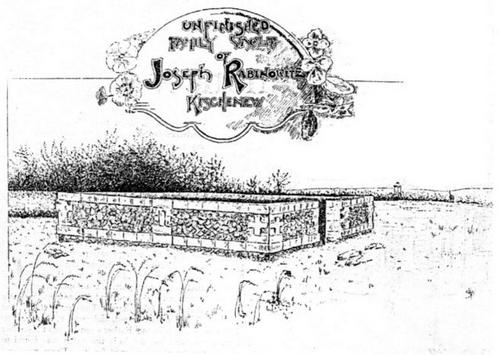

It was particularly important to give instructions on the order of paperwork and funerals. In pre-revolutionary Russia, the registration of births, marriages and deaths was handled by the church. But after his baptism Joseph left the rabbinate but did not join any of the Christian churches. In this case a death certificate could be issued by the police. The will stated that immediately after death one had to go to the local police station. The funeral was to be carried out according to local Christian procedures. Joseph did not want unnecessary ceremonies and asked that only his children attend the funeral. The coffin was to be placed in one of the niches of the family vault he had built in the cemetery of the New Testament Israelites, a niche in which he had placed the Hebrew Gospel during his lifetime.

page30

It was only a year and a half before his will was fulfilled. In the autumn of 1898 Joseph suffered from malaria, which made him very weak. On 23 January 1899 he held his last service at Somerville Hall. In March he became worse and on the advice of doctors he went to Merano, for treatment, to a spa town in South Tyrol, accompanied by his daughter Sarah. He had no hope of returning and before he left he gathered the whole family together, blessed everyone and told them where his will was. The air of Merano briefly improved his condition. On 22 April Joseph returned to Kishi. As his son Ivan later wrote, returning to a city where malaria was rampant was a fatal mistake. His father became worse and Sarah and Peter took him to a sanatorium in Odessa, where he died at one o'clock on 17 May 1899.

page31

The next morning, the coffin containing Joseph Rabinowitz's body, accompanied by Pastor Kornman of the Reformed Church, was transported to Kishinev and placed in Somerville Hall, where a memorial service was held. In accordance with his will, Joseph was buried in the family crypt built during his lifetime in the cemetery reserved for the New Covenant Israelites outside of town, next to the Karaites' Jewish and Armenian cemeteries. The crypt consisted of eight compartments, with Joseph’s occupying the first. On the tomb was inscribed

"An Israelite who believed in JehovahThe grave has not been preserved.

and his anointed one,

Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

Joseph, son of David, Rabinowitz. "

Joseph Davidovich did not leave a successor, although in the last years of his life this issue was discussed many times. After his death, there was no one willing to continue the work he had started. It may seem strange that none of his sons followed in his father's footsteps. They shared his views, were baptized, and helped in his work, but none of them became preachers. All of his sons left for study in Petersburg or Moscow after graduating from a grammar school or high school. When Joseph converted to Christianity and began preaching his doctrine among the Jews, his eldest son Vladimir was already an adult, working as a railway engineer in Ungern. The father had to rely on the younger sons, Ivan or Peter, who were baptised as teenagers. But they were in grammar school and did not have the deep religious feeling and interest in holy books that Joseph had from his childhood. Understanding this, their father helped them to be educated according to their inclinations and choices.

page32

After Joseph's death the small group of his supporters broke up. The reason for this was not so much the absence of a preacher as the conditions under which the New Covenant Israelites prayer house existed. We can agree with Kai Ker-Hansen that any, even the best preacher, who continued Rabinowitz's work could only postpone the collapse of the community, not save it. For 13 years Somerville Hall stood unused. Only in November 1912 the Mildmay Mission renovated the house of worship and reopened it. However, permission from the authorities to hold Messianic sermons could not be obtained. In 1913. Somerville Hall was leased to the Evangelical Christian Community. In 1917 the building was put up for sale, and in 1921 it passed into private hands. According to L.N. Tolstoy, the teachings of Joseph Rabinovich had no future. But more than a hundred years passed and the Jewish Messianic community revived in Kishinev. Now it is called "Bnei Brith Hadasha", or translated from Hebrew as "Sons of the New Testament". Its founders remember Joseph Davidovich, who was the originator of the Messianic movement in Kishinev, and publish his proclamations. There are Messianic communities in Moscow, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, Israel, Germany, the United States, and many other countries. So the cause of Rabinovitz great-grandfather, lives on.

page33

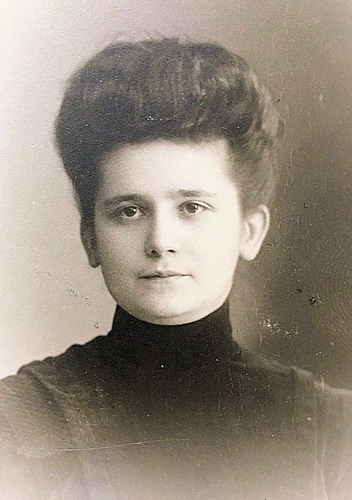

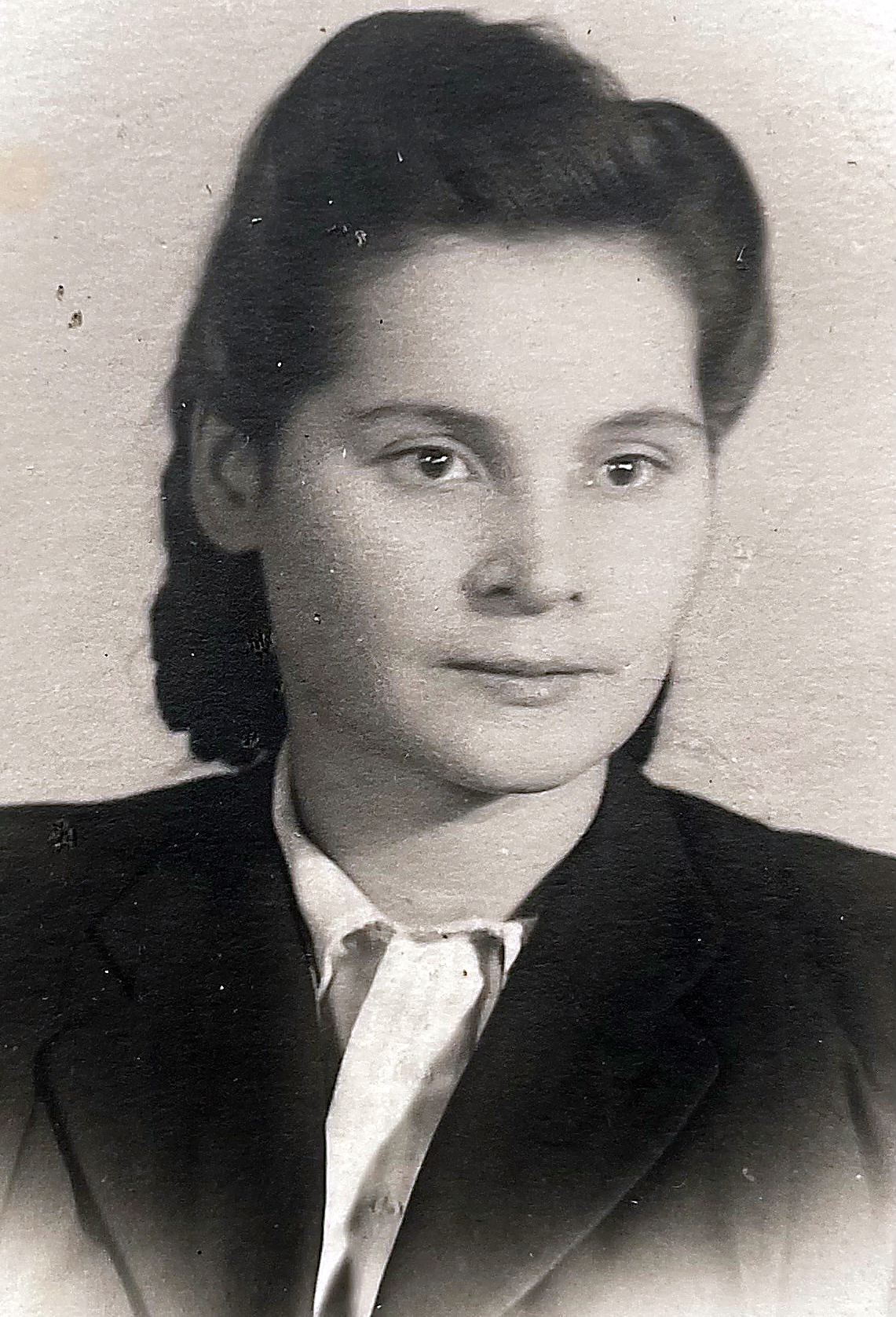

Olga (Golda) Danilovna Rabinovich (1839-1913)

What do I know about my great-grandmother? Almost nothing. She was in the shadow of her famous husband, and all the references to her are connected only with him. The most important thing in her life was her family, her children, her home. For the sake of her family, she took the courageous step of abandoning the faith in which she had been brought up and followed her husband and children and adopted Christianity. It is safe to say that her life was a success. She lived 74 years, was surrounded by a friendly and loving family, and had prosperity and well-being in her home.

Golda was born in 1839 in the county town of Orheev, owned by the landowner Princess Elena Hangerli.

From various records it is possible to reconstruct the names and dates of Golda's family from grandfather Elia Gershkovich Goldenberg (or Goldenbark) (1774-1840) and grandmother Bailey (b. 1795), her parents - father Daniel Eliovitch (b. 1817) and mother Sura (1818 - between 1854 and 1859). In addition to Golda, Daniel and Sura had three other daughters, Nehama, Rehma and Bryana, and a son El, who died at the age of ten. Sura died at the age of about forty, and Daniel married again to the thirty-five-year-old Hava.

page34

Golda did not have to live with her stepmother; she was already married. In July 1853 she was betrothed to Joseph Rabinowitz, who was a year older than she was. They may have known each other, but matchmaking was a matter for the parents, and the feelings of the children were hardly taken into account. In December 1854 they were married. According to tradition, Joseph moved in with the Goldenbergs for the first year and a half of their married life together. Given the young age of the newlyweds, this was quite reasonable. Joseph was a man of letters and his interests did not change with his marriage. Golda's chief concern was children. She gave birth to seven. Their first child, Haim-Wolke was born on September 13, 1856, followed by Sarah in 1857, Rebecca in 1866, Rachel in 1869, Tikva in 1870, David in 1874 and Nathan (my grandfather) in 1876. If you look at the birth dates of the children, you can see that there was no addition to the family between 1857 and 1866. Rebecca was born nine years after Sara's. This is due to the unfortunate events (the fire and the death of the Tikva) described above. Over the next ten years, life began to improve becase of Joseph's legal practice

page35

In November 1871, the Rabinowitz family moved to Kishinev, settled into a rented house in the town. The death of little Tikva was a great shock to her mother. Life nevertheless followed its course. Joseph worked hard. The older children were growing up and Haim-Volke had left for study in Petersburg. Immersed in domestic cares, Golda was scarcely aware of her husband's thoughts and actions. What totally surprised her was the spiritual upheaval that Joseph underwent after his return from Palestine in 1882. Raised in an Orthodox Jewish family, she could not agree with her husband's new ideas, but could not argue with him either. When Joseph was baptized, Golda bitterly lamented that such a learned and respected man of the Jews had bowed his knees to the despised Jesus of Nazareth. She felt deeply for the children who had followed their father and been baptized. Several years passed before Golda herself took the step. This important event for the whole family took place in Budapest in 1891. The city was not chosen by chance. Rachel had been sent to Budapest for a year after the two years in Edinburgh. Joseph and Golda wanted to see how their daughter would settle in, but the main objective was the baptism of the mother.

The sacrament took place on October 5, Golda received the name Olga, the same day Joseph sent a telegram to the children from Budapest to Kishinev. It contained only two words in Yiddish: "Mama gerettet" (Mama is saved). The atmosphere in the Rabinowitz household is testified by Samuel Wilkinson who stayed with them during his trip to Kishinev. He writes about the hospitality of the hosts, the evenings spent with the family. There was a wife and three daughters at home, English hymns were sung in the evenings, Samuel played the piano and Joseph played the violin.

After her husband's death, Golda Danilovna was left to live with her daughters in the family home. With the loss of the breadwinner there was nothing to live on. Only her eldest son Vladimir, who worked on the railroad, had a steady income. But he lived in another city and had his own family.

page36

The younger sons Ivan and Peter were students and needed help themselves. A report about the plight of the Rabinovitz family and an appeal to wealthy people to help the widow and children, was published in the Mildmay Mission newspaper. Money began to arrive from Joseph's foreign friends and comrades-in-arms. Somerville Hall remained the property of the family, despite the fact that it was built with money borrowed from Joseph's Scottish friends. In 1903 the debt expired, but was not claimed by the creditors. There was discussion about Mildmay Mission renting the building to use it as a house of worship. The lease would have been a help to the family and a joy that Joseph's work was continuing. But it didn't work out. It took another 11 years until Joseph Rabinowitz's property was deemed free and clear of liens by the courts.

page37

In April 1903 the Jewish population of Kishinev experienced terrible days. On April 19, the first day of Passover, a pogrom began. Shouting "Christ is Risen Again", pogromists burst into the homes of the Jews, smashing and looting their shops, beating men and women and throwing children out of the windows. The pogrom was triggered by P.A. Krashevan's articles about the brutal murder of fourteen-year-old Mikhail Rybachenko, allegedly committed by Jews for ritual purposes. The murder was described in grisly detail, which aroused a desire for revenge. All the more so because the only daily newspaper in Kishinev, Bessarabets, had been waging an anti-Semitic campaign long before the pogrom. It appeared that the boy had been killed by his relatives, but the Ministry of Interior forbade the publication of materials about the case and the slander was not publicly refuted. The police did not intervene. In two terrible days 47 people were killed, 92 were seriously injured, 700 homes were destroyed, 600 shops were looted and 2000 families were devastated.

page38

The Rabinovitz family was not hurt, but was frightened. A few days after the pogrom, S.H. Wilkinson and P. Wolf (a missionary living in Odessa and receiving funding from Sweden) came to Kishinev and brought money to help the victims of the pogrom. A small amount was given to the Rabinovich family.

Testament

In July 1908 Olga Danilovna made a will. She owned at that time one-seventh of the real estate inherited from her husband. The will required that part of the house and the money left after her funeral be divided equally among her children. Wherever she died, she wanted to be buried according to Christian rites in Kishinev in a crypt next to her husband and an inscription quoted from Psalm 22 of King David:

If I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,One phrase in the extract from the deed book of Kishinev notary P.P. Zalevsky, who executed this will, was unexpected for me: "This will at the personal request of illiterate Olga Rabinovich was signed in our presence by the nobleman G.M. Benkevich.

I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me;

Thy rod and Thy staff they comfort me.

Amen

page39

None of her autographs have survived. One explanation remains: Olga Danilovna's native language was Yiddish and she probably could not write in Russian.

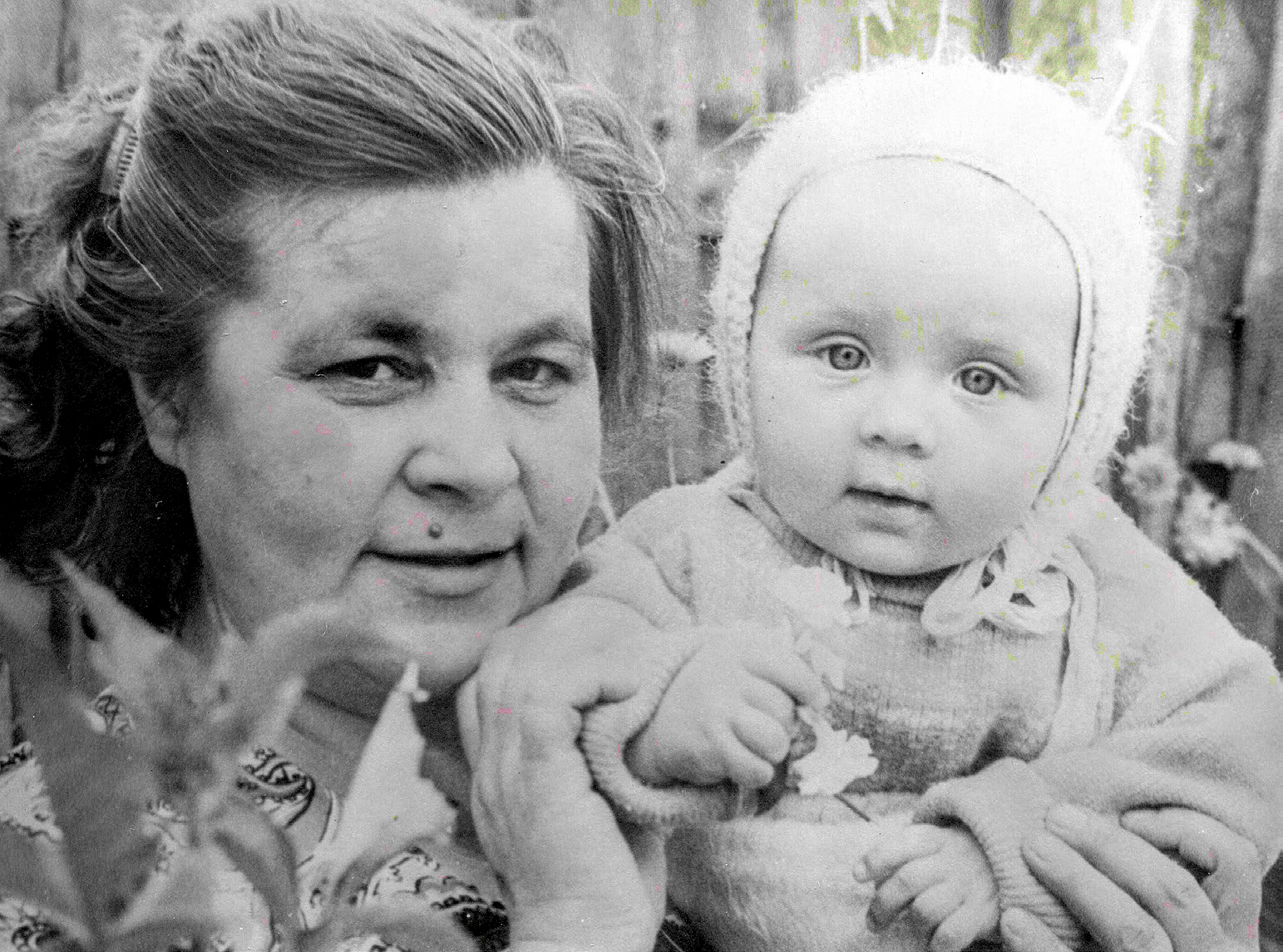

The last years of her life Olga Danilovna lived together with her daughters, unmarried Rebecca and Rachel, who returned to Kishinev after the birth of her son Andrew. Of great concern was the deteriorating health of her eldest son Vladimir. His early death hastened his mother's passing. Olga Danilovna died on December 13, 1913 and was buried next to her husband.

page40

The story of the Rabinovitz family would not be complete without the stories of their children and grandchildren. There were six children, the youngest , my father was born in 1915, and nine grandchildren. All except my grandfather Peter, and his children will be discussed here. Separate sketches are written about them. The children of Olga Danilovna and Joseph Davidovich had different lives, they were scattered in different cities and countries, but they preserved warm and close relations for the rest of their lives.

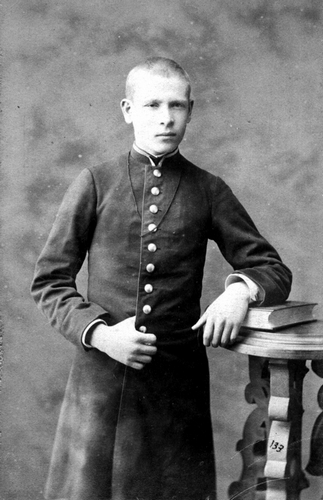

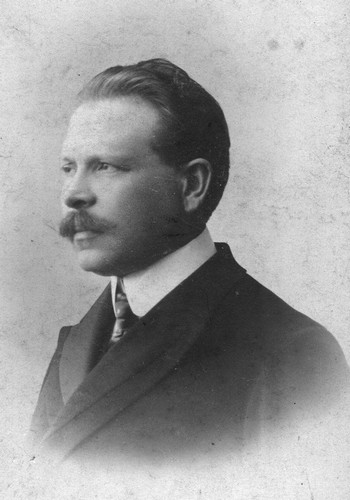

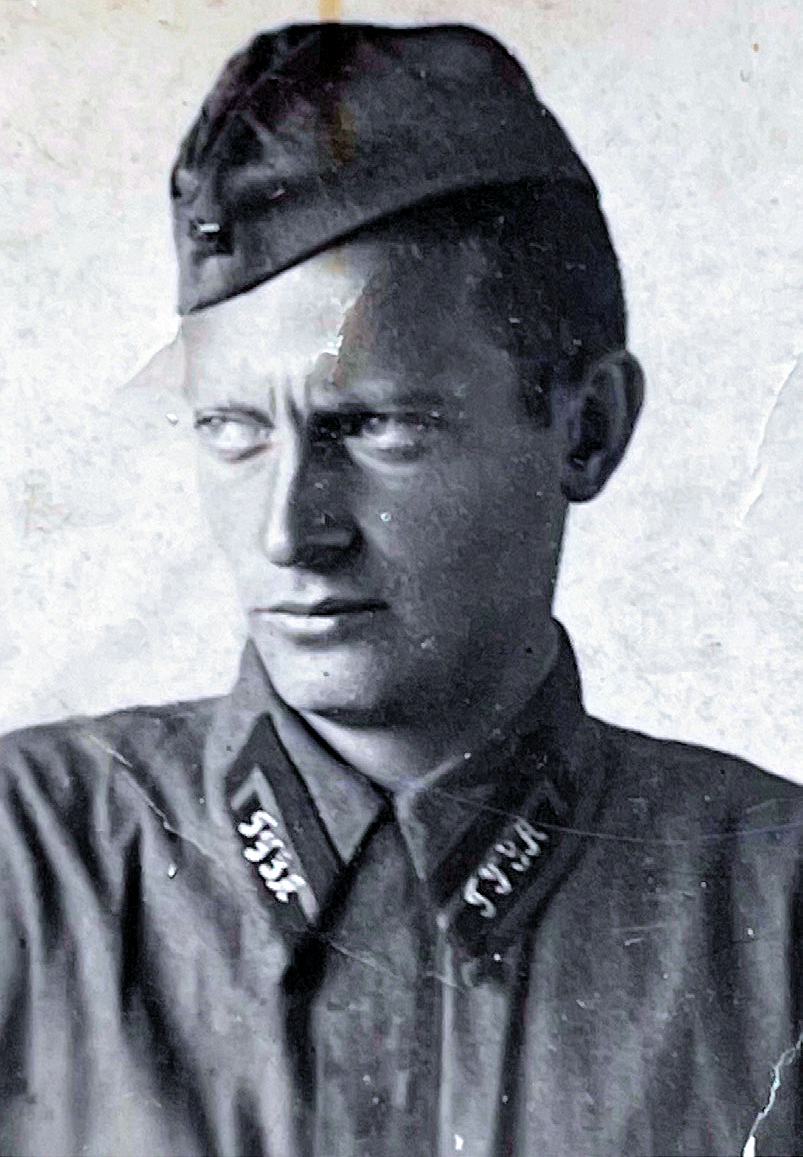

Vladimir (Chaim-Wolke) Josephovich Rabinowitz

Chaim-Volke (Vladimir's birth name) was born in Orgeev on 13 September 1856. When he was three years old his house and all his belongings burned down and the family became poor. It is likely that the young family was sheltered by Golda's parents who lived in the same town. So Chaim-Wolke's early childhood was probably spent at his grandparents' house. Gradually his father Joseph managed to get back on his feet. The family income was sufficient to provide the only son so far with a good education. In 1871 the family moved to Kishinev and Chaim-Volka was admitted to the Kishinev Normal School, which opened in December 1873. There were four classes in the main branch and an additional mechanical-technical class.

page41

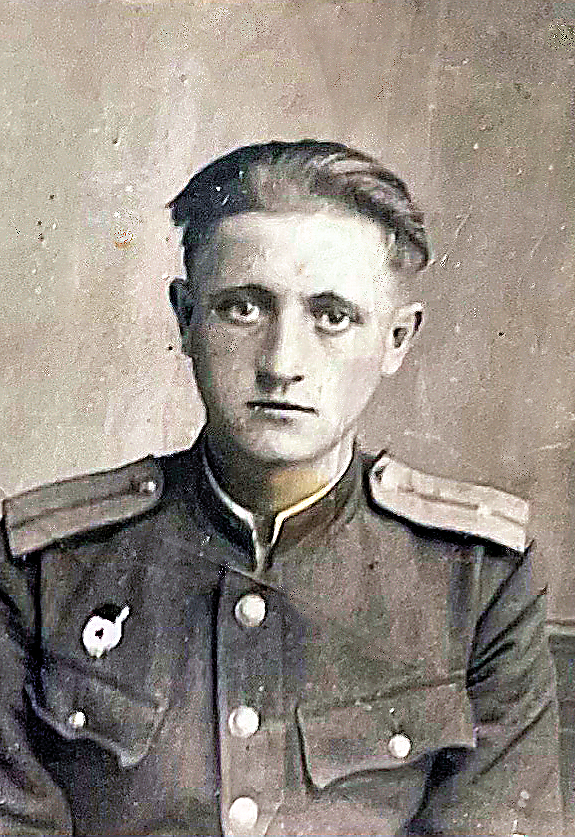

In 1876 Chaim-Wolka turned 20 and was due to join the army. But he was lucky - at the recruitment process he was granted an exemption from military service and enlisted in the militia. He was therefore able to continue his studies. Haim-Wolke entered one of the best technical colleges in Russia - the Alexander I Institute of Railway Engineers. In 1883, having completed a full course at the Institute, he received the title of civil engineer with the right to perform construction work and the right to the rank of provincial secretary on joining the civil service. Chaim-Wolke's first job was with the Belgian Joint Stock Company of the Odessa Horse and Steam Railways. He spent three years in Odessa, where he was engaged in constructing the city transport network, and then was appointed assistant chief of the section for repair of buildings in the Society of South-Western Railways with a salary of 1200 roubles per year and moved to Kiev. Between Odessa and his appointment in Kiev the most important event happened in Chaim-Volke's life, on 23 August 1886 he was baptized in St. Petersburg French Reformed Church, and given a new name - Vladimir. It was just a year and a half after his father was baptised.

page42

1856 - 1913

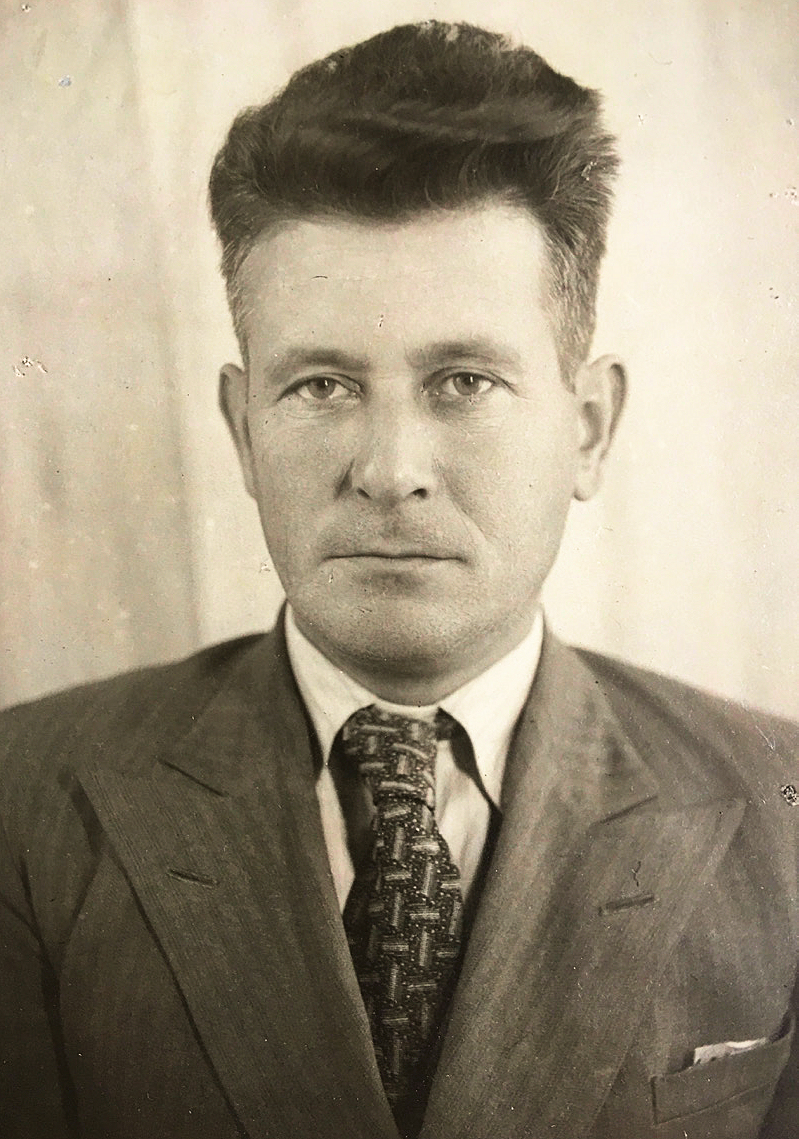

In February 1990 Vladimir was transferred to Ungheni as assistant head of the railway. It was a village on the border with Romania with a population of about two thousand, which began to develop rapidly after the construction of the railway. On October 4, 1892 at the age of 36 Vladimir married the 19-year-old daughter of the merchant Julia Avanesovna Dragunova, of the Armenian Gregorian faith. The family settled in the town of Bila Tserkva on Smolyana Street in the house of Herczyk. On 9 August 1893 Vladimir and Julia had a daughter, Victoria and on 18 July 1897 a son, Alexander. The children were baptised in the Kishinev Evangelical Lutheran Church. The family grew and expenses increased. Vladimir began to clamour for an increase in position and salary and a transfer to another station. As the years passed, Vladimir gradually rose from the 12th civilian rank to the 8th: in 1897 - collegiate secretary, in 1898 - titular adviser, in 1902 - collegiate assessor, which in the army corresponded to the rank of major. However, moving up in the table of ranks, he remained in his former modest position of assistant chief of the station.

page43

He repeatedly applied to the Railway Administration for a transfer to a new position. In the autumn of 1898, he got his chance - a vacancy had opened up on the Kharkov-Nikolaev Railway. Vladimir had taken three weeks off for a trip to St. Petersburg. He received a copy of the service record at his workplace and the job went through the chain of command. The Chief Inspector of the Ministry of Transport reported Rabinovitz's application to the Minister. The Minister was ready to support him, especially as not all of the section chiefs had the appropriate education. The inspector wrote a letter to V.A. Myasoedov-Ivanov, head of the Railway Administration. The letter was on ministerial letterhead, but its content was far from formal. It said that the engineer Rabinowitz was a Jew who had converted to Christianity with his entire family, "having lost touch with Jewry, he evidently has not managed or has not been able to make friends among his Christian co-workers and needs some support from his superiors". According to the Inspector, Vladimir enjoyed the patronage of the late D.I. Zhuravsky. This correspondence resulted in a letter from the Ministry to the head of the Kharkiv and Nikolayev Railway, supporting Engineer Rabinovittz's request. Encouraged, Vladimir travelled to Kharkov in February 1899. However there it turned out that there was no vacancy for him and it was not known when he would get one. There was some small consolation in the promise of a job as soon as the site manager's position became available. However, eight months had passed since his trip, and the letter from Kharkov had not arrived. During this time he had lost his father, to whom he was very attached.

page44

A further letter from Vladimir, sent to the Inspector of the Ministry of Transport in September 1899, is full of despair. He describes himself as a "battered and forgotten engineer". He asks for help to get out of this "damned island" and writes that he is capable of more varied and independent activities than that of an assistant section chief. For the sake of his family, he is prepared to accept the post of Section Chief or another suitable post on any road within European Russia. The Ministry enquired with the Chief of South Western Railways about the moral and service qualities of Engineer Rabinovitz and the possibility of his promotion. The reply left no hope: "The moral and service qualities of Engineer Rabinowitz are satisfactory, but as for his promotion to a higher position, this cannot be done on the South-Western Railways. Repeated appeal from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs The fact that there were no vacancies for the head of the railway section did not bring the desired result either. Vladimir worked as an assistant section chief for the rest of his life. We do not know why Vladimir's career was not successful. But it is clear that the situation in which he found himself was burdensome. The monotonous job, the lack of money, the absence of any perspective in life, and the social isolation was having devastating effects on his health. The first symptoms began at the age of 35. They began to worsen in early 1900. In March, Vladimir submitted a report requesting six weeks' leave and a cash allowance for medical treatment. The report was accompanied by the medical board's conclusion that Mr. Rabinowitz, 43 years old, "suffers from degeneration of the posterior columns of the spinal cord in the initial stage" and needs to be treated with hydrotherapy and electricity. He received a leave of absence, but the treatment didn't help.

page45

The illness progressed. He was examined by a medical committee in 1901 and 1902. The complaints remained the same: Lower back and leg pain and general infirmity. In 1902, Vladimir again received six weeks' leave and a medical grant. His treatments had continued, but the illness had not abated. A report of the medical board in 1911 stated that he had been suffering for many years from an unknown cause, complaining of intermittent pains from the lower back to the toes, general weakness, rapid fatigue, heaviness and headaches in the evenings. In May 1912. Vladimir has requested leave for 4 weeks for urgent domestic circumstances. It is possible that his mother had fallen ill. Vladimir has only received 2 weeks holiday which he has not used in full - he left for Kishinev on the 27th July and returned on the 4th August. The following year Vladimir requested 6 weeks sick leave for treatment abroad but only received permission for 2 weeks. This was not enough time to travel abroad and undergo a full course of treatment. Each year his health deteriorated.

page46

Doctor's report dated 5 August 1913 stated that Vladimir Iosifovich Rabinowitz "suffers from arteriosclerosis of the tangible arteries, frequent attacks of heart palpitations, chronic articular rheumatism of the lower limbs and haemorrhoids. These seizures are accompanied by frequent headaches and general malaise. In order to cure these illnesses it is necessary for him to undergo radical treatment and to abstain from all mental and physical work. But he was not given leave for treatment and could not leave his job. On October 24, 1913. Vladimir Iosifovich died suddenly of a ruptured heart at the age of 58. He was buried in Kishinev in the family vault next to his father. Julia, who was left with two children, was given a pension of 181r. 25 k. per annum from the emeritory fund of the railway engineers. The sum was miserable, and it was impossible to live on that money. During the last five years Vladimir's salary amounted to 2160 roubles a year, of which 720 roubles for salary, 720 roubles for rent, 360 roubles for canteen and 360 roubles for travelling allowance. Julia applied for a pension from the treasury. It turned out that Vladimir's seniority entitled him to a pension only for a reduced term of service.

The hassle about the pension lasted more than a year; we had to have the medical statement that due to health condition Vladimir was entitled to pension during his life, the certificate from the Bila Tserkva grammar school, confirming that her son Alexander was studying at his mother's expense, and also the certificate of Kyiv governor, that Julia had not lost her right to receive the pension. Whether the widow's efforts were successful, is unknown.

In 1916. Yulia Avanesovna moved to Kiev and in November 1918, five years after Vladimir's death, at the age of 44 years old she married the son of a provincial secretary, Matthew Josephovich Lisetsky, aged 29. The children were already adults.

page47

Victoria Vladimirovna Syrokomskaya

Victoria was born on 9 August 1893 and in September the same year she was baptised in the Evangelical-Reformed Church in Unghene. She is known to have graduated from the Kiev Conservatoire in piano. Since the Kiev Conservatoire was transformed in 1913 from the music school of the Kiev branch of the Russian Musical Society, it can be assumed that Viktoria received her initial musical education at the music school. It is known that after the death of Vladimir Iosifovich, Yulia Avanesovna and the family was in need, when she applied for a pension, enclosed a certificate stating that her son was studying in a grammar school at her expense, but who was paying for Victoria's Studies? None of her closest relatives, neither her grandmother nor her uncles were able to pay for her tuition. It is likely that Victoria studied at public expense, which means that she must have had outstanding musical ability.

On 21 April 1917 Victoria was re-baptised in the Sretenskaya Church in the Second District of Kiev and was anointed with the Holy Anointing, admitted to the Orthodox Greek-Russian Church. And two days later, on 23 April, she married the hereditary nobleman Nikolai Franzevich Syrokomski, aged 29.

page48

One year later, 7 April 1918, their son Vladimir was born.

Nikolai worked as an engineer on the South Western Railway. While films were silent,Victoria was a pianist working as an accompanist in cinemas, and giving music lessons.In 1939 Nikolai Franzevich died.

When the war began, Victoria and her son were in Zhmerinka. The Germans were advancing so quickly that the city was captured on 16-17 July 1941, Victoria and Vladimir were in occupied territory. It was not until March 1944 that Zhmerinka was liberated by Soviet troops. In autumn 1945 they managed to return to Kiev. After the war, Vikcoria worked as a typist, and in the evenings she moonlighted as a music teacher.

I never saw Victoria, but I knew that my father's cousin lived in Kiev. I remember her son Volodya, who used to come to Moscow and stay with us. Victoria used to send greeting cards from Kiev for the holidays. The last one came after my father's death. Victoria passed away in 1971.

page49

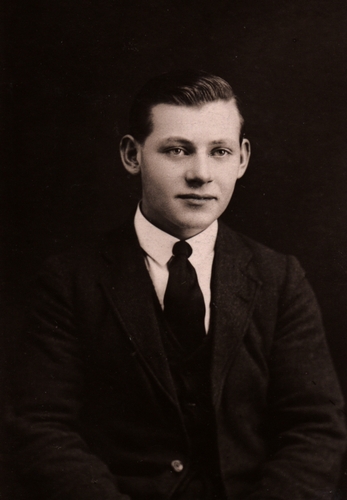

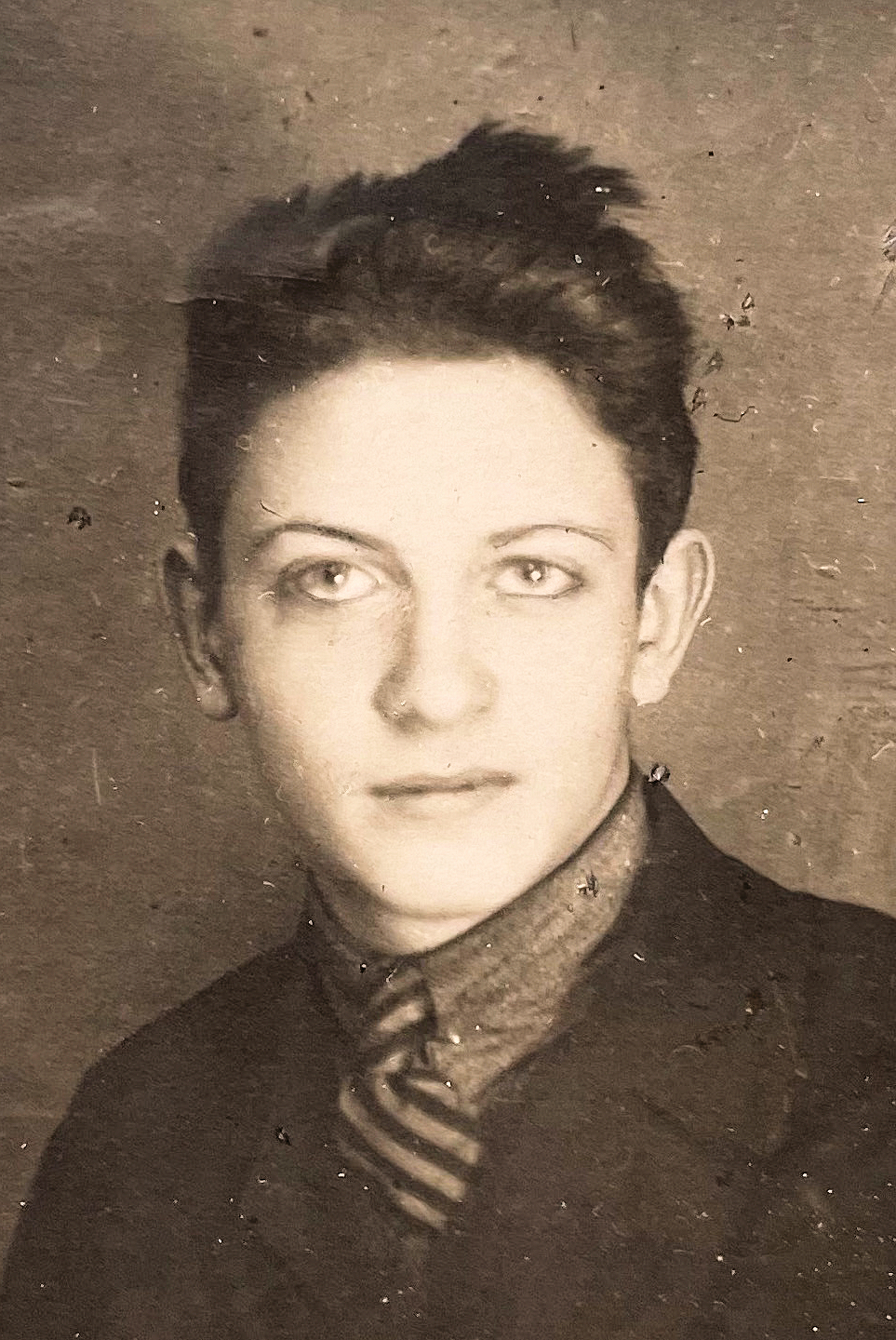

Alexander Vladimirovich Rabinovitch

Alexander was born on 18 July 1897 in Ungheni, and was baptised in the Kishinev Evangelical-Lutheran parish. His aunt Rebecca Rabinovitz was present at the baptism. When his father died, Alexander was 16 years old and was studying at the gymnasium in the town of Bila Tserkva. His family was in need, so he had to work part-time in parallel with his studies. After graduating from high school in 1916 he and his mother moved to Kiev, where he entered University

In 1917 under the Provisional Government, Alexander was drafted into the army and sent to the front as a private motorcyclist.

At the end of the same year, a Soviet decree exempted him from military service as a student.

During the civil war, when power in Kiev was changing hands, Alexander joined the Jewish communist party Poale Zion (after the party disbanded in 1923, most of its members joined the Russian Communist Party but Alexander remained non-partisan).

Like his sister, Alexander was drawn to music. In 1920, he dropped out of university to attend the Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama. In 1923 he entered the Conservatoire, taking a class in composition theory. He wrote in his questionnaire that he earned his living through "Soviet service" and lessons. He worked most often as a statistician, and his jobs changed frequently.

He graduated from the Kiev Conservatory in 1925, but he felt his education was not enough to do what he wanted - scientific work. His path to science was long and arduous, but he made it.

page50

To continue his education, Alexander moved to Moscow. Here he had first and foremost, to find a job. Alexander joined the lamp factory as a statistician, and in 1926 the pencil factory of A. Gammer, where he worked until the autumn of 1928. He needed the money to pay for his studies and help his mother, who remained in Kiev. There he married L.D. Volpin, but the marriage soon ended and in 1928 Alexander re-married Fanny Yakovlevna (Freya Yankhelevna) Roitbarg. Fanny worked as a shorthand typist and interpreter for the Executive Committee of the MOPR.

In 1927 he enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory to study music acoustics at the Faculty of Composition Sciences. He completed the conservatory course in two and a half years, as some of the subjects he had taken at the Kiev Conservatory were relavent.

The tuition fee at the Moscow Conservatory was 36 roubles per year. Alexander applied for a reduction in the fees, as he had his wife and mother as his dependents, to whom he sent 15-20 roubles monthly to Kiev.

page51

In addition his earnings at the factory had been reduced due to the fact that he had to take time off from duty to attend classes at the conservatoire. The following year, however, tuition fees were raised to 64 roubles. This amount became unaffordable for Alexander, as the factory went through staff cuts in September and he was dismissed. The Conservatoire Commission had to release him from payment of tuition for half a year. After leaving the factory, Alexander found a job more suited to his specialty, but at a lower salary. He enrolled at the State Institute of Musical Culture as a research technician with a salary of 70 roubles, half the salary of the factory. In January 1930, Alexander graduated from the conservatory, by which time he had a number of published works, including a textbook on acoustics, adopted as a compulsory textbook for students of the Moscow State Conservatory. In 1930 Alexander enrolled for his post-graduate studies and went to work at the Moscow radio broadcasting centre (MRTU) as a director of radio broadcasting. However, the same year he was fired due to being late for work after his leave, and Alexander moved to the Moscow Sound Film Factory as a mixer and then an acoustician. He then worked in an acoustics laboratory at the Institute of Communications, did research, and in 1940 defended his PhD in acoustics. By this time the family had three children, Jacqueline (1931), Victor (1934) and Julius (1937).

page52

During the war, Alexander was drafted into the army. In his first year he was taken prisoner. Half-Armenian, half-Jewish, bearing the surname Rabinowitz, he only survived by miracle. He was saved by his profession - the Germans were interested in experienced specialists in the field of acoustics - and he was sent to a camp where he worked in his profession. After his liberation in 1945, the Allies offered him a move to the US, but Alexander returned to Moscow, where his wife and children were waiting for him. Almost immediately, a neighbour denounced him and he was arrested and sent to a camp in the Urals. His wife and children followed him. After Stalin's death he was amnestied, but the family did not return to Moscow. Alexander began to teach physics and mathematics at school. The years spent in the German and Stalinist camps undermined his health and he did not live long after his release. He passed away in 1961.

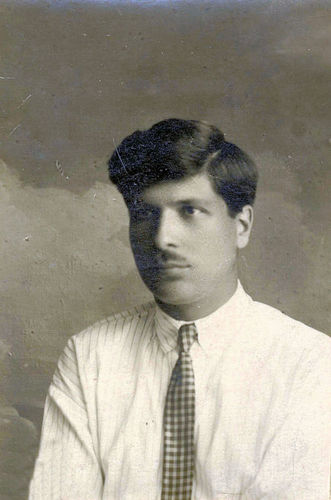

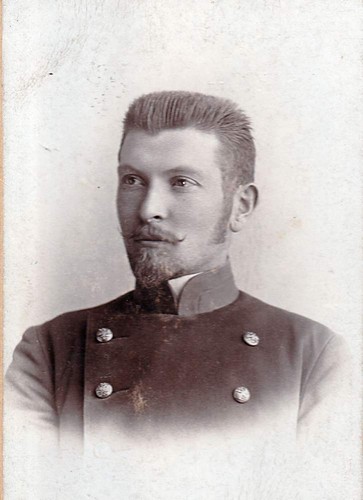

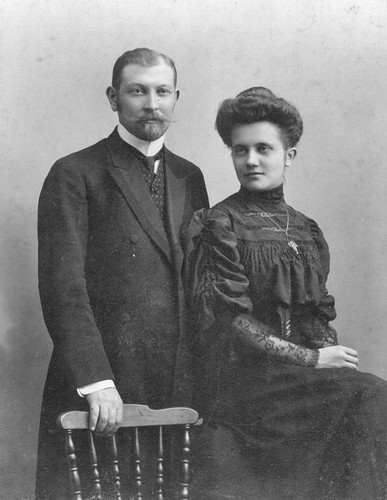

Sofia (Sarah) Josephovna Offenheim

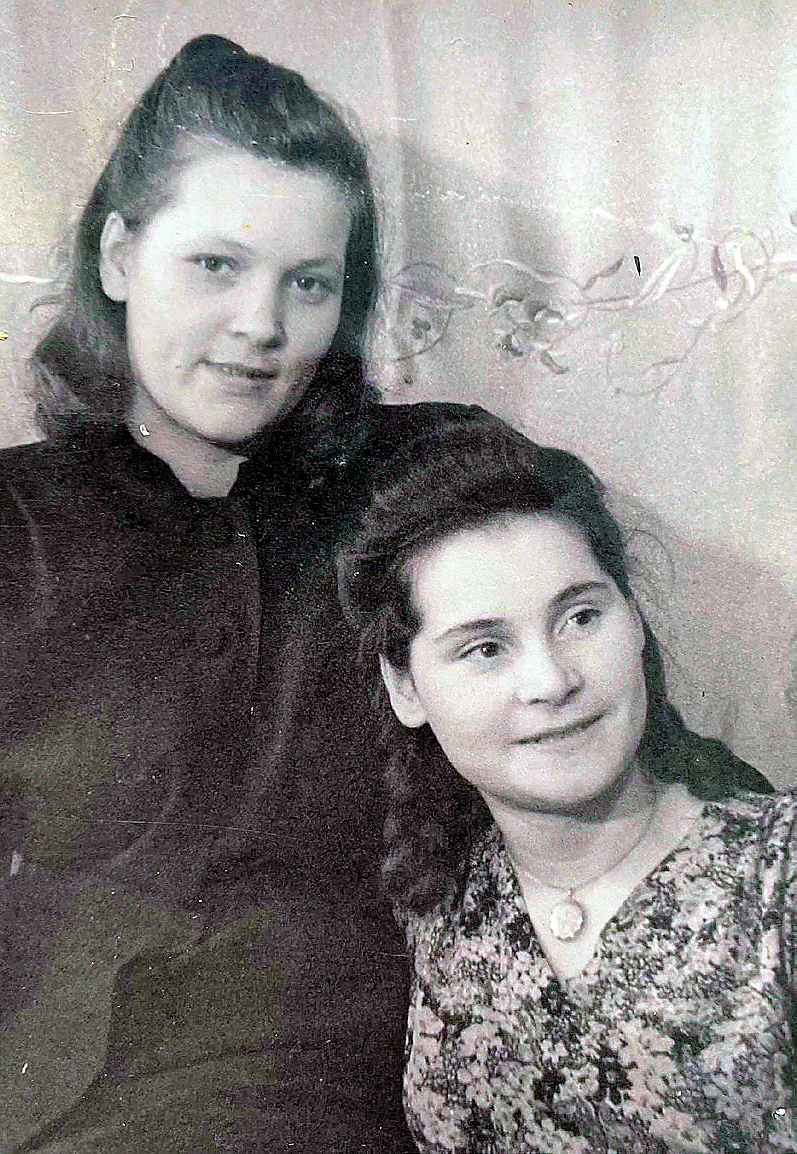

Sara, the eldest daughter of Golda and Joseph, was born in Orhei Sara like all of Joseph's children received her father's teachings and was baptized with her sisters in the Reformed church at Rohrbach near Odessa on 4 October 1887. There is only sketchy information about the subsequent events in her life. She was married twice but had no children. There is a photograph of her and her first husband, Joseph Axelrud, dated 1879. We do not know where they lived or what her husband did for a living. The family was probably destitute. In one of her letters to her sister Rachel, Sophie mentions that in 1885 she went to went to work "on a milk co-operative farm".

page53

. In 1890 Joseph Davidovich arranged for his son-in-law to work as a representative of the Mildmay Mission in Odessa. Axelrud often travelled to neighbouring towns and distribute religious literature among the Jewish population. He died in 1893 during an epidemic of cholera. After her husband's death Sofia returned to her parents. She helped her father and was by his side until his last days. In March 1899 Sofia accompanied Joseph on a trip to Merano and after his return to Kishinev together with her brother Peter (my grandfather) they took Joseph to a sanatorium in Odessa, where he died.

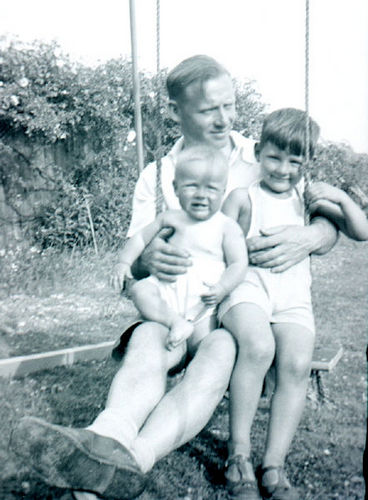

Sofia's second husband was Ilya Offenheim from Kiev and in 1903 they became the adoptive parents (godparents) of Rachel's son Andrew, who was born and baptised in Moscow. Whether they were living in Moscow at this time or came especially for the baptism of their nephew is not known. In a letter to Rachel in 1937. Sofia writes that she had been living in the flat for 22 years. Was it her first Moscow flat? This means that she moved to Moscow no later than 1915. Her address is known: Tverskaya, Georgievsky Lane, 1, Bldg.22. It was here in October 1921 that Sofia's younger brother Peter stayed with her when he arrived in Tverskaya from Arkhangelsk in search of work. In January 1922, Peter moved his entire family to Moscow, he left his younger sons with his sister while the older ones helped their parents in their new home.

page54

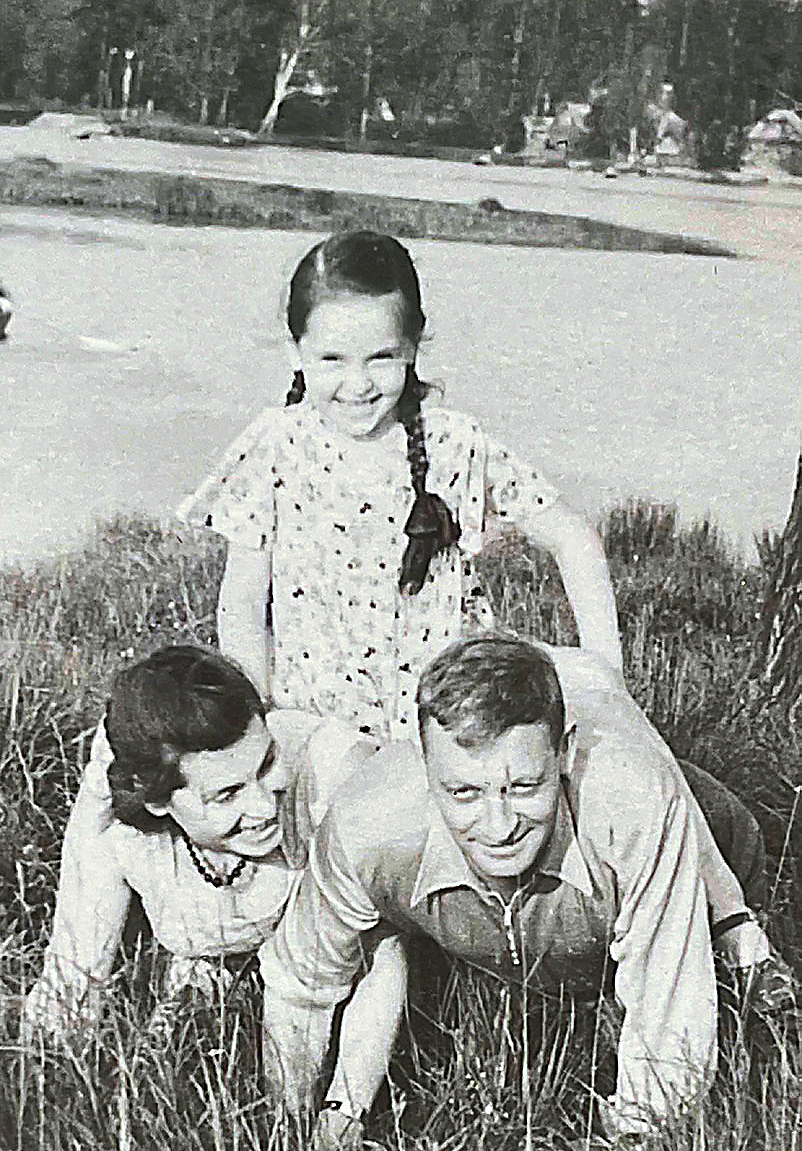

Moscow, 1928.

From Sofia's letters to her sister in England, we know that Joseph's children retained a very warm kinship. The family all gathered at Sofia's and Ilya's house for the new year celibration of 1926/7. There was brother Peter with his wife Glasha and younger sons, Pavlik and Rostik (my father), brother Ivan with his wife Mirra Kalistratovna. On New Year's Eve they wrote a letter to their sister Rachel in England, each adding a few words.

Sofia, the only one among all Joseph Davidovich's children, retained her connection with the Messianic movement. This is evidenced by the representative of the Swedish Jewish mission, B. Shapiro, who visited Moscow in 1928 and met Peter, Ivan and Sofia. According to Shapiro, the sons said that their father's cause lives on, there is a Jewish Christian group in Moscow, but they have no contact with it. They are far from Christianity and have no interest in religion. Sophia, on the other hand, was happy that God had heard her prayers and she had found fellow believers again.

page55

In 1932 Ilya died and Sofia was left alone. In one of her last letters to England, written on 20 March 1935, she wrote that she was growing weaker by the day but that she tried to devote all her mental and moral energies to go on living. She was 78 at the time. She was very ill, especially with her legs, for several months she was confined to her flat, as she lived on the third floor and could not get down. Her brothers helped her financially, but did not visit her often. They worked a lot. Peter brought food once a month. Everyday help was provided by neighbours in a communal flat. Rachel sent 10 shillings twice a year, which was a help. This money could be used to buy groceries at Torgsin. A lonely, sad old age. But her letters were full of warmth and love for her sister and brothers. She rejoiced over the successes of her nephews, brightened her loneliness by reading newspapers, proudly wrote about the success of the Spanish Republicans at Guadalajara.

Rebecca Josephovna Rabinowitz

Rebecca Rabinowitz was born on July 20, 1866.in Orgeev and died on November 12, 1914 in Odessa from lung tuberculosis, briefly surviving her mother. She was baptised in the village of Rohrbach, Odessa County, Kherson Province October 4, 1887. Nothing more is known about her. She was unmarried and, and lived with her parents all her life.

page56

Rebecca did not leave a will and her estate was divided by the court between her brothers, sisters and nephews, children of her elder brother Vladimir. Rebecca's estate consisted of one-sixth of her parents' house at 20 Meshchanskaya Street and a deposit in the Kishinev City Public Bank. Altogether, 4,848 r. 40 kopecks. This sum was divided among five heirs.

Rachel Josephovna Kinna

Rachel was born on 1 January 1869 in Orhei. On October 4, 1887, she was baptized with her sisters in the village of Rorbach, Odessa County, Kherson Province. Where she studied is unknown, but when she went to England with her father in 1889, she already had a working knoledge of English and was able to help him. She was admitted to the newly opened Deaconess School in Edinburgh. This school was set up for women who wanted to serve in church parishes, work in overseas missions or be nurses. For several years the Deaconesses practised as nurses in the newly built Deaconess Hospital. Rachel's stay and training in Edinburgh was paid for by funds allocated by the Church of Scotland to the family of Joseph Rabinowitz. Accommodation and meals at school cost £1 per week. Rachel lived at the School for the first year and with a local family for the second year. After graduating from the School, Rachel returned briefly to Kishinev and then was sent to Budapest for a year. Her time at the School left indelible memories in Rachel's heart and had a huge impact on her later life. She became fluent in English which enabled her to assist her father on his trips abroad and to earn a living through teaching.

page57

Rachel made a very good impression on A N Somerville, who visited Kishinev and was a guest of Rabinowitz. Somerville wrote: "his [Joseph Rabinovitz's] youngest daughter is a remarkably attractive and intelligent girl, she speaks English well and helped her father in conversation". After her Joseph's death, Rachel moved to Revel, where her younger brothers Ivan and Peter lived. There were probably more job opportunities there than in Kishinev. In Revel she began teaching English and Russian. Where and how she met the Scotsman John Kinna is unknown. It could have been in Scotland while she was studying in Edinburgh or in Revel where John was looking for a teacher of Russian.

page58

In April 1902 they were married. John worked in the Moscow branch of the American photographic materials company Kodak. He was 41 and Rachel was 33. On June 25, 1903 they had a son, Andrew. Shortly after his son was born John left for England and did not arrive in Moscow until mid-September. When he returned, Rachel and her young son went to Kishinev to stay with their mother. In fact she and John parted ways and further contact between them was reduced to letters, only two of John's letters survive. In 1906 one was addressed to Andrew, who was then 3 years old, and another in 1917 was sent to Revel.

Rachel moved to Revel in 1914 after the death of her mother. She and her son settled in the same house with the family of her brother Ivan. With the outbreak of the First World War, Revel became the base of the Russian Baltic Fleet. There were many servicemen and sailors in the town. Rachel began giving private lessons in English. Unexpectedly, among her pupils, who responded to an advertisement in the newspaper was a Japanese officer, who had arrived in Revel to escort heavy canons for the Russian army When the revolution broke out and the Provisional Government came to power in Petrograd, the country was thrown into chaos. Some Estonian political forces wanted autonomy within Russia, others hoped to gain full independence with the help of the German forces, radical parties grew in influence, and Bolshevik slogans gained in popularity. Prices rose, and life in the city became increasingly difficult. Rachel's archives include a letter from John received from Moscow on 26 July 1917. John complained of stomach problems and wrote that he would not be able to come to Revel: "After the visit of your brother I have been ill for about two weeks".

page59

Since correspondence between them was rare, it can be assumed that Rachel's address to John and her brother's visit to him were prompted by special circumstances. Perhaps it was about emigration to England. As for the brother, it was probably Ivan, with whose family Rachel was close and who was also about to leave Revel. The other brother, Peter, was at this time living in Arkhangelsk.

In September or early October 1917. Rachel and her son left Revel. They did so in a hurry, taking only the bare necessities with them, including a small wicker basket containing the family photographs.. Andrew told his son David that when they left they buried all their silver under the house

A certificate from St Peter's Normal School dated 7 September 1917, confirming that Andrew was a Year 5 pupil, and documents dated October 1917 confirming the sale of the house where they lived, have been preserved.

Their journey to London took about two years. They first travelled to Petrograd, where Rachel received a new passport on 17 October. From Petrograd, Rachel and Andrew may have stopped in Moscow, where John, Rachel's older sister Sophia and brother Ivan lived. Whether they met John is not known. In any case, John remained in Moscow, where he died of typhus in March 1920 .Their next stop was in Perm, where Nadezhda, brother Ivan's ex-wife, was living with the children. This is confirmed by a letter addressed to Rachel: Perm, Voznesenskaya Ploshchad, 35, sq.2, and dated 24 April 1919.

page60

Perm, like the rest of the country, was in turmoil. The city changed hands: at the end of 1918 it was captured by A.V. Kolchak's army, in the early summer of 1919 the Red Army went on the offensive. The financial system was disorganised. After unsuccessful attempts to obtain money in exchange for the State Loan Shares, Rachel and Andrew travelled further East. They travelled by train in a crowded carriage. Many years later Andrew would tell his son David how his mother slept in the carriage on the floor, putting things under her head so they wouldn't be stolen, and that at the stations he would go to the engine for boiling water . Finally, on 30 August 1919. they reached Vladivostok. Rachel obtained a new passport and on November 1, 1919, she and her son managed to get on the steamer 'Monteagle' carring the 1/9th Hampshire Regiment, returning from Yekaterinburg

page61

On 16 November the steamer docked in Vancouver, Canada. With the regiment, Rachel and Andrew crossed Canada by train, then boarded a ship and on 5 December 1919 arrived in Southampton. From there, their paths with the Hampshire Regiment diverged. Rachel and Andrew went to London.

Rachel and Andrew were given refugee status, given ration cards and had to find accommodation. Rachel wrote to John Kinna's brother, William, who lived in Tottenham, a district of London. But his family couldn't accommodate her and her son, they just didn't have the space. It was from William that Rachel learned of John's death.