page185

PARENTS

The older I get, the more I remember my parents. I often have the same dream: I urgently need to call my mum or dad, I haven't visited them in a long time, I feel ashamed, I grab the phone, but I can't get through. Mum and Dad lived together for about 15 years, some of that time they were happy, otherwise they couldn't have made my childhood happy.

Thanks to them for that.

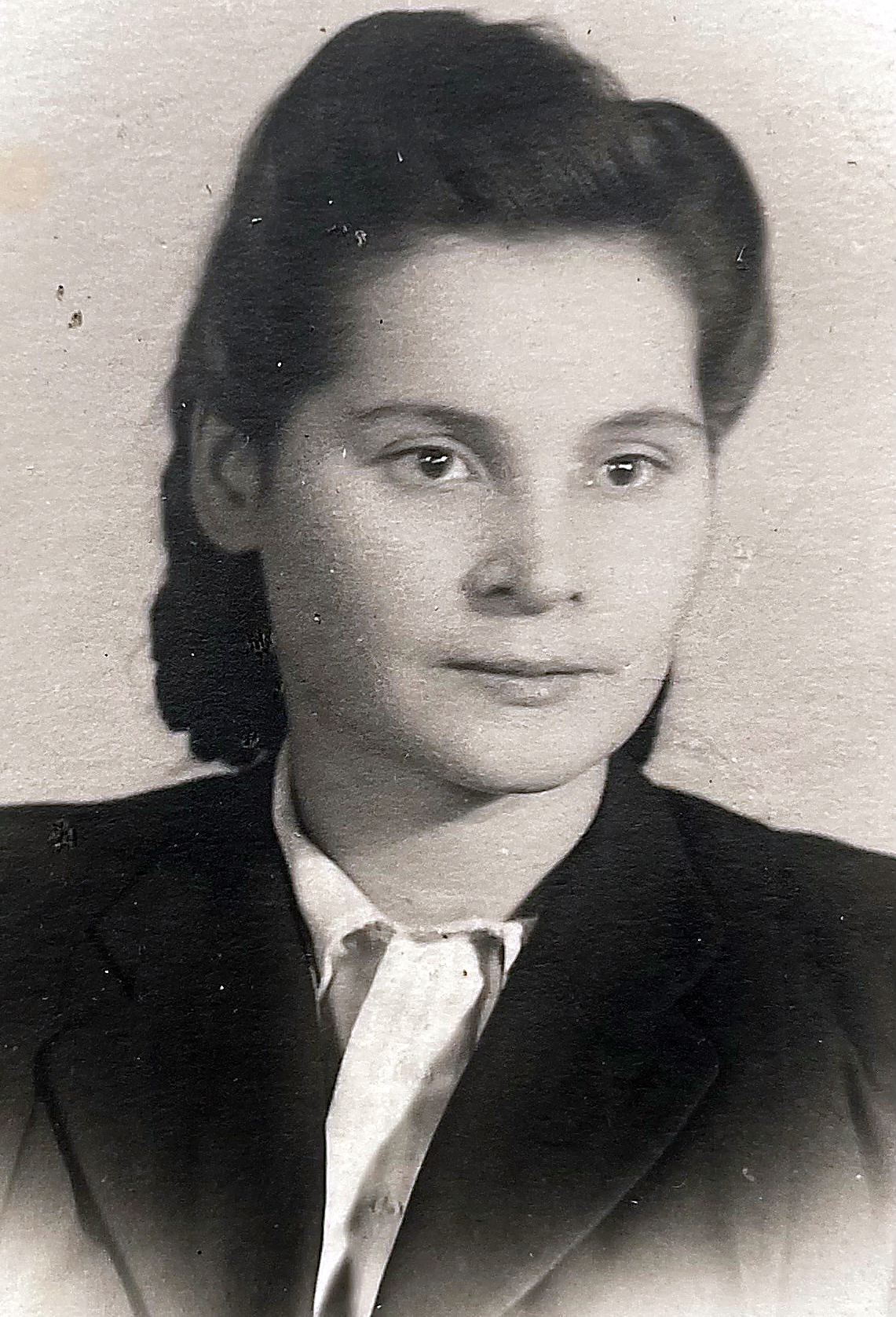

Nina Vasilievna Bratseva

Childhood

My mother was born on 23 February 1925, the date on which we always celebrated her birthday, although all the documents indicated a different date, 24 December 1924. Why this happened is unknown. That date appears on her birth certificate dated August 5, 1936. The handwritten document form says "copy", but I suspect that before she was 11 years old, Mum simply did not have any birth certificate. The compulsory issue of birth certificates by the local authorities, and their uniform format, was not established until 1935. This was the first time that Mum received one, and it did not list her parents. Not only was there an error in the date of birth, but

page186

Maria Yegorovna, 1932-1933.

The name of the village is "Adriapol" instead of "Andreapol". The name was corrected, but the date of birth remains for the rest of her life. The school was in Andriapol, 25 kilometres from Zabolotye. It was too much for the girl to travel that way every day, so Nina had to stay overnight with relatives. When her mother retired, she said that she would write her memoirs "My childhood without a doll", but she told me very little about her childhood. One story she remembered was that she was walking home from Andreapol, an aunt caught up with her on a horse-drawn cart. She asked for a ride, but the aunt just whipped the horse and sped away. I imagine a small, tired girl walking along a forest road and try to understand what was behind it. Heartlessness or a personal grudge against Vasily Panfilovitch? Probably both.

page187

Nina was said to resemble her father in appearance: high cheekbones, slightly slanted eyes. It is difficult for me to judge, there are no pictures of my grandfather. He was arrested in 1930, Nina was only five years old. Vasily Panfilovitch's first term ended in 1933, and he was arrested again in 1937. My mother sometimes said that she was glad I had a "good biography". Only when I grew up, I understood what she, who had been branded the daughter of an enemy of the people all her life, meant. In her CVs and questionnaires, she had to write that her father had been dispossessed and then convicted under Article 58. She recalled how bitter it had been when she was rejected from the Pioneer camp at school, and how she had had to struggle to be accepted into the Komsomol and the Party. She always tried to do her best in school and work hard. I remember my mother coming home from work one day upset. A colleague, with whom she was friends, called her the daughter of a fist.

page188

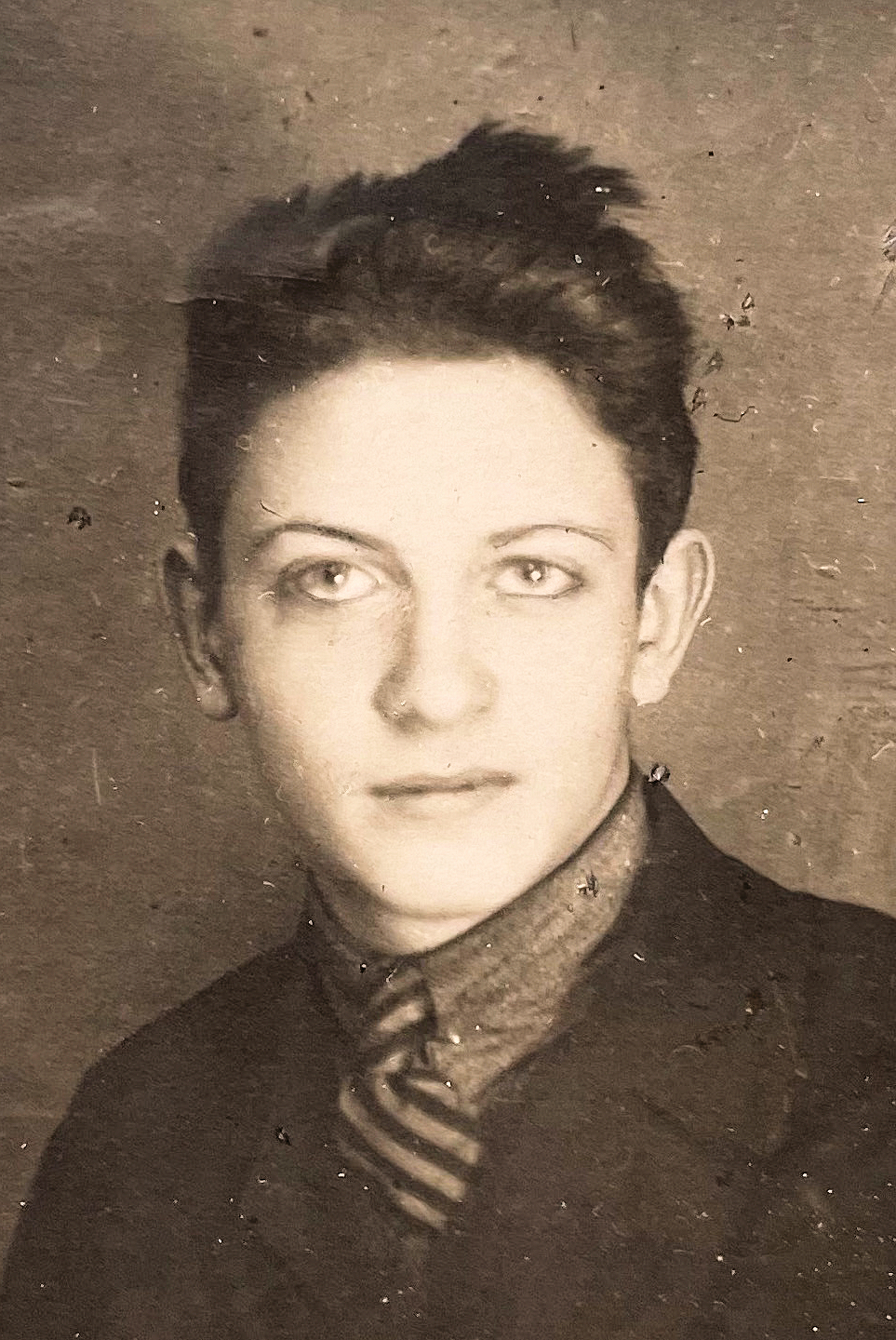

Shura right in the second row, 1939.

Khrushchev's rehabilitation of victims of Stalinist repression did not affect the peasants who had suffered during the years of collectivisation; my father was only rehabilitated at the end of the Soviet regime, when my mother was retired.

During the war

Nina was 16 when the war started. She lived with her mother Maria Yegorovna in Zabolotye. Her father was in prison, her elder sisters were married, Shura lived in Moscow with Marusya. The Red Army was retreating, in August the front was approaching the Andreapol district. Marusya was calling for her to evacuate with the academy where she worked. Not to burden her sister, Nina and her friend decided to make the long journey to the Urals on their own. There, in Verkhny Ufaley, lived the family of Major Nikitin, who had stayed in their house during the retreating battles. The major wrote to his family to help the girls. Nina and her friend travelled a thousand kilometres to a complete stranger's house with this letter. They were welcomed and helped to find a job. Mum finished the course and joined the staff in July 1942 as a junior laboratory assistant

page189

in the chemical laboratory of the Ufaleisky nickel plant. I do not know how Nina's friend's fate turned out, but for my mother the Nikitin family became family for the rest of her life. Every time my mother's "brother" Zhenya, son of Major Nikitin, and his wife Zoya came to Moscow, they visited us. The friendship with Olga Velichko, with whom my mother worked in the laboratory, lasted a lifetime. It was wartime, the girls from the factory performed for the wounded in the hospitals. Nina recited poetry and sang. She had a good voice in her youth. From the childhood I remember my mother singing "Here under alien sky, I'm like an unwanted guest..." and songs of Vertinskiy, whose concert she managed to visit. She came back home in 1943. But her name is missing in the estate books of Zabolotye. Judging by Alexander Parshikov's letters addressed to "Andreapol Poste Restante",

page190

Nina lived in Andreapol until the autumn of 1944. She probably worked in the Komsomol district committee or at the local newspaper. Since November 1944 letters from the front started to come to Velikiye Luki to the regional committee of Komsomol.

My mother met Sasha Parshikov in Andreapol at the beginning of 1944. She was 19, he was 22. Sasha was a native of Byelorussia from Bogushevichi village in Berezina district of Minsk region, he had studied at technical institute before the war in Leningrad. On the front junior engineer-Lieutenant Parshikov served in aviation corps in communication company. The corps was stationed for some time at a military airfield 3 kilometres from Andreapol. The acquaintance was short. The war was going on, our troops were moving to the West. Sasha's first letter was written

page191

in March 1944, the last one in March 1957.

March 1957. More than 60 letters in all. My mother kept them through numerous moves and two marriages, and I only dared to read them 20 years after her death. It was an affair of very young people, in which a crush turned into a friendship due to external circumstances. The war was coming to an end and the question of the future arose, but Sasha neither offered nor promised anything. He wanted to continue his studies in Leningrad, his family would have been a serious hindrance. He constantly advised Nina to go to school. My mother was keen to do so herself.

Komsomol Central School

In 1945 Nina was taken to the Velikoluky Regional Komsomol Committee as an instructor in propaganda. It was a great leap in the career of a twenty-year-old girl. Perhaps it was connected with her joining the party. It was not easy for the daughter of an "enemy of the people". At first she was rejected. Nina did not give up and wrote a letter to the secretary of the regional party committee, referring to the words Stalin once said that children are not responsible for their fathers. She was summoned to the Obkom of the All-Union Communist Party(b), they talked to her. Such militant girls with a good tongue and writing were needed by the Komsomol, and she was accepted.

page192

The date Nina joined the Party was February 1946, before which she was supposed to be a candidate for at least a year. I believe the story of my mother's entry into the Party began in Andreapol, she was taken as a candidate in the Regional Committee. Here she was admitted to the Party and sent to the newly established six-month courses for Komsomol workers at the Central Komsomol School. She went to Moscow to study with her party card.

The Komsomol training center was the only place where people could be enrolled. It was a privileged educational institution. It was situated in Veshnyaki, near the Kuskovo estate, in the suburbs of Moscow. Students received a scholarship of 900 rubles per month, were provided with dormitory, three meals a day and study aids. Attention was also paid to the appearance of the trainees. In January 1946, the Central Committee of Komsomol decided to give men one shirt and two pairs of socks, and women one blouse and two pairs of stockings, as well as 200 grams of laundry soap and three boxes of matches

. After a six-month course, Nina was accepted on a two-year course. Teaching was based on the curricula of teacher training institutes. Students studied Soviet and general history from antiquity to the present, the history of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, international relations, political economy, mathematics and ismatism, Russian and foreign languages, and literature. Unlike in teacher training institutes, there was no pedagogy but the history of the Party was studied in more detail. The students were divided into three

page193

departments. My mother was a student in the youth press department. On her transcripts, her grades were mostly excellent, few good and none satisfactory. The student years were probably the happiest of her life. Mum often reminisced about them, and continued to be friends with many of her classmates, Zoya Yakhontova becoming her closest friend for the rest of her life. When I told Sergey Sergeevich Dmitriev, who was head of the history department at the CKCS in the post-war years, that my mother had studied with him, he remembered 'two Ajaxes', as he called inseparable friends Nina and Zoya. His friendship with Leonid Pochivalov and Valentin Kononenko lasted a lifetime. And now, turning over the pages of my graduation album of 1948, I meet familiar names of my mother's classmates, who used to visit us at home. The Central Committee for personnel training for the regions and my mother received an assignment to Velikoluksky Regional Committee, from where she came to study. But there was no suitable position there, or maybe she managed to persuade the secretary in charge of human resources. I remember my mother talking about Kostya Vishnev, who helped her a lot. She returned to Moscow and got a job as head of the editorial office of Young Bolshevik, the Komsomol Central Committee magazine. She moved in with her older sister, Marusya,

page194

in a nine-metre room in a communal flat. To move from a city in ruins to the capital was a great stroke of luck for her and, as it turned out, for me.

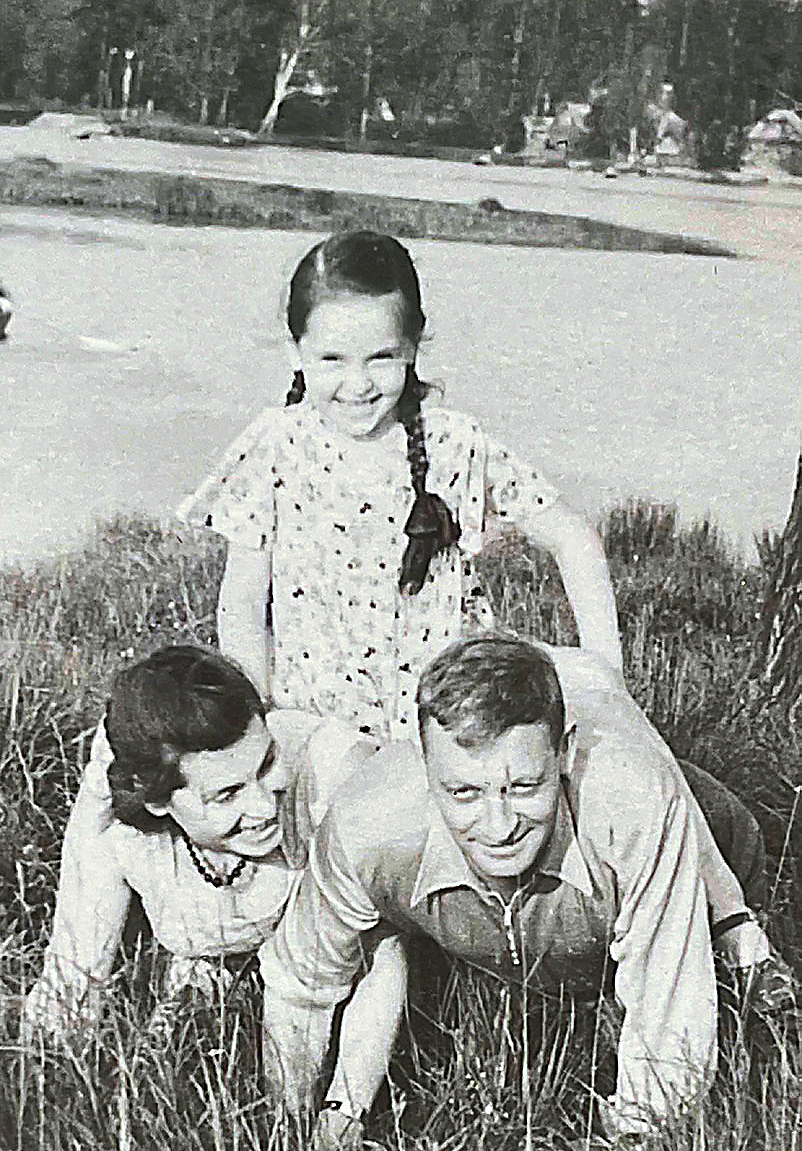

Marriage. Glazovsky Lane.

She met my future father at the magazine's editorial office. Rostislav Dadykin was a postgraduate student at the Institute of History and temporarily worked at Young Bolshevik as head of the Marxist-Leninist theory department. Their romance was swift. On September 9, 1948 Mum was hired by the publishing house, and they were married on October 24. My mother told me that my father proposed to her using the word "you". She was 23 and he was 10 'years older.

They settled in Glazovsky Lane in the communal flat where Rostislav's parents had lived since the 1920s. They had a separate room, which at that time was a luxury. Many started their family life in the same room as their parents, at best shielded by a wardrobe. Their room was entered through their grandmother's, who slept behind a screen. Dad's older brother Seva's family lived in the next room with their two children, and their nanny lived in the hallway behind the wardrobe. There were also neighbours - three sisters, one of them with her husband and daughter. There was no bathroom or hot water in the flat. So the bathing of children, washing of adults, washing and drying took place in the shared kitchen. I vaguely remember the kerogas and primushers we cooked on, and the smell in the shop where we went to get paraffin. Then came the gas cooker. All this was the norm, and many of my childhood friends and classmates lived in far worse conditions. I think my mother, who grew up in the countryside, lived in a dormitory, and a rented house in Andreapol and Velikie Luki, did not experience any domestic difficulties. She got on well with her mother-in-law.

page195

She had a relationship with Lina, Dad's brother Vanya's wife, and with Dad's nieces Olya and Nina. A former neighbour, Georgi Nikolaevich, used to visit us on University Avenue. The education I received at the CKCS was equivalent to an incomplete higher education Mum didn't want to stop there, I think Dad supported her in this. In April 1949, she enrolled in a correspondence course withh the Department of History in the Moscow State Pedagogical Institute . She was accepted as a student at once, taking all the courses she had taken at the CKCS, but she was required to take two more exams. But she didn't have to study. A month after giving birth to me , my mother went back to work, and during the lunch break, rushed home to feed me, thankfully the editorial office was relatively close by. Combining work and a baby was difficult, and with schooling simply impossible. It was probably because of me that in November 1949 my mother went to work as a newsreader, and 4 years later returned to be in charge of the editorial office. It was a difficult time for the family. Dad was writing his dissertation and had to resign from the magazine in August 1950. He did not work for half a year, and they lived on Mom's salary alone. At that time an event happened that influenced the rest of Mom's life. She became pregnant. I was one year old, my parents could not afford another baby. Abortion was forbidden at that time, on pain of criminal liability. There was only one thing to do.

page196

turn to the aestheticians,who did it at home illegally. Criminal abortions often ended in complications. That's what happened to my mother. She could no longer have children.`

In May 1951, Dad defended himself, and the following year he was hired as a junior researcher at the Institute of History. Life became easier. Soon my father's brother Seva got a separate flat and we got the room. Natasha, the housekeeper who worked for Seva, also joined us. This was a great relief to my mother. Natasha did all the housework, shopping, cooking, cleaning, and looking after me. After my grandmother died, our living space expanded even more. We had as much as three rooms.

Studying at the High School and a new job

Mum didn't give up her dream of higher education. In 1960 at the age of 35, she enrolled in the journalism department of the Moscow Higher Party School. Once again, the student.

page197

In those years the whole system of education in the country was restructured under the slogan of strengthening the link with life. After Khrushchev announced, at the 20th Congress of the CPSU, that the party's educational institutions were training workers "who did not know the basics of concrete economy", the curriculum of the High School urgently included courses in cattle breeding, mechanization and electrification of agriculture, technology of major industries, etc. My mother's classmates, many of whom worked in different branches of industry and agriculture, helped me prepare for the credits and examinations in these subjects. They often met at our house. The only "satisfactory" grade in my mother's report card was in industrial and civil engineering.

I had to study for four years, but in less than two years the Moscow Higher School was transferred to Leningrad, leaving Moscow as the only place to go. Mother had to go back to work in the magazine and continue her studies by correspondence. She finished the remaining courses in one year early in the spring of 1963 and received her diploma at the age of 38. She was the youngest of the sisters and the only one to receive a higher education.

While still a student, in May 1962, mother was transferred to the position of deputy executive secretary of the magazine (now called The Young Communist) and a year later she became executive secretary. In December 1964 she transferred to the magazine Agitator. In December 1964 she was transferred to the magazine Agitator as Deputy Executive Secretary. This was considered a promotion because Young Communist was published by the Central Committee of the Komsomol and Agitator by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. I must admit that I was saddened when my mother told me that she would be working at the Agitator. It was a thin propaganda magazine that no one read. True, it had a huge circulation, but that was only due to its price. Party members were obliged to subscribe to the party press and most chose the cheapest edition. I dreamed that my mother would work in some

page198

popular literary magazine, such as Yunost, Novy Mir or Foreign Literature. But fate decided otherwise.

My mother wrote to Alexander Alekseyevich about her first day at her new job: "I got to know my colleagues. They are all respectable and venerable, intelligent and party-minded. Mother herself had never been respectable even at an older age. She was cheerful, sociable, easy to get along with people and quickly fitted in with the new team. Working in the Party magazine offered few privileges, essential at a time of growing scarcity. Thanks to Agitator, she had a separate two-room flat after her divorce from my father. A special cupboard offered products not available in ordinary shops. In summer, you could rent a room or cottage at the state dacha, and in winter you could go there for the weekend. Mother worked at Agitator for 24 years, until she retired.

Divorce and New Marriage by Alexander Brattsev

Alexander Alexeyevich Brattsev

The 1960s were a time of big changes in my mother's life: her studies and graduation from the High School, her transition to a new job, divorce, new marriage, moving to a new flat. My finishing school and going to university should be added to that, as it was also a time of much excitement.

I don't remember exactly when the breakdown in our family began. I can only guess at the reasons, and I don't want to write about them. My mother started having problems with her thyroid on a nervous basis, and she was seriously ill. My parents' final divorce was a relief for me and, I think, for them as well. Very soon Dad and Mum had new families. In May 1965 my mother married Alexander Alexeyevich Bratcev. Their romance, which developed before my eyes, annoyed me. At the age of 15 it seemed to me that

page199

at their age, you don't fall in love, and Mum only needs to get married so she won't be alone at her old age. My mother was 40, and Alexander Alexeyevich was 43. For years I had thought that my mother's hasty marriage after the divorce was solely an act of self-assertion, a response to my father's marriage. After reading their correspondence, I saw that this was not entirely true.

They met in Leningrad when Mama was visiting Shura's sister's house. There was a family party of some kind, and among the guests were neighbours, Shura's friend Sonya and her husband Sasha. Mum and Alexander Alexeyevich started a correspondence, writing and calling each other almost every day. Their letters are full of tenderness, love and care for each other. From his letter: "After my mother, you were the only one who showed me real care and attention. Almost every weekend Alexander began to come to us in Moscow, laden with gifts. Every time he came, it was a festive occasion, with guests gathering and dancing. He used to sing "I met you and all the past..." I can't stand that romance ever since.

They met when they each had 16-17 years of family life under their belt, going downhill. There were teenage children with whom they had to explain themselves somehow. Aleksandr Alekseyevich had a more difficult time in that respect than my mother. In the autumn of 1964, having left the family, he wrote to her: " Suffering for Yurik, I'm sorry for seventeen 'very badly lived joyless years." Divorce in those years was not easy. All sorts of barriers were erected to preserve the "Soviet family". Divorce cases were public, announcements about them were printed in local newspapers. I remember such an advertisement about my parents' divorce in the Vechernyaya Moskva, after which friends poured in to reconcile them. Communist divorce cases were often sorted out at work in the party committees. And in the characteristics of the divorced, it was obligatory to write that the Party Committee knew the reason for the divorce. Mother and Alexander went through all this.

page200

Sonia, Aleksandr's wife, did not work and tried her best to hold on to her husband. There was shouting, threats and cursing at home, and at work talks with the secretary of the institute's party committee and the rector. The last straw was a letter to the Party Committee from the village of Suzun, where Alexander's parents lived. As if visiting his parents, Colonel Brattsev had seduced his neighbour's wife and destroyed the family. The party committee sent an enquiry to the Suzun district committee. A personal case was made about the morality of the Communist. As a result, Alexander Alekseevich was reprimanded, but not for destroying the Suzun family, but for not helping to save it. The whole story half a century ago now looks ridiculous and ludicrous, but it cost Aleksandr Alexeyevich a lot of nerves and health. "Losing weight, grow old, turn grey," he wrote to Nina.

page201

Mum also had to explain herself in her party office. As I was surprised to learn from her letter, Dad had come to her work about the divorce case. Mum was extremely indignant. Fortunately, this was before her move to the Agitator. Finally, in March/April 1965, the divorce proceedings were over and they were married on 21 May.

I was lying at home that day with angina and had no idea that I had a stepfather. Only by the tension and excitement of Aunt Marusya, who stayed with me, I sensed that she was hiding something. Finally the phone rang, I heard "Congratulations," and I guessed what it was all about. Of course, I knew my mother was going to marry Alexander Alexeyevich. It was all going to happen, and she asked me if I minded. But it was a bit frustrating.

Next came the question of moving Alexander Alexeyevich. to Moscow. Mum said she was ready to move to Leningrad herself, but there was a place to live in Moscow, Mum had a good job and the prospect of a separate flat. For half a year they lived in two cities. In January 1966 we moved to Universitetsky Prospekt and soon Alexander moved in. He got a transfer to the Sports Committee of the Ministry of Defence. After the communal flat in Glazovsky Lane, a separate two-room flat with a bathtub and hot water seemed posh. It was the first flat of my mother's life and she lived in it for the rest of her life.

page202

The first years with Aleksandr Alexeyevich were happy. We all travelled together to Suzun to visit Aleksandr's parents. We fished in the Ob River and spent the night in a tent. Alexander Alekseevich got on well with his son Yurik and he began to come to us from Leningrad. Mum and Alexander Alekseevich were keen on building a dacha. At that time, plots of land were being distributed all over the country and garden associations were being set up. This was done partly to make up for food shortages, partly to ease the pressure on the consumer market of the money supply accumulated by the population. My mother got her six acres in Veliaminovo from work and the work boiled over. With great enthusiasm they planted apple trees, currants, strawberries, dug beds. It was more difficult with construction, since building materials were in short supply. My sister Vera helped out by sending us planks and timber from Kalinin. In summer, Veliaminovo became the holiday destination for the sisters with their children and grandchildren. Often friends came to visit. They were accommodated, as they say, in cramped quarters, but not in misery. The house was small - six by six metres, the kitchen was arranged in a shed. There was also a sofa to sleep on. We spent the holidays at the cottage. In December 1971 I got married, mother and Alexander Alekseevich were left together. The following year my mother became a grandmother. It is difficult for me to judge from the outside, we lived separately, but it seems that it was at this time that the changes in my relationship with Aleksandr Alekseevich began. Now often after work my mother would rush not to her husband's house, but to her grandson's. She would bring bags full of groceries. She came back late and tired. Alexander must have felt sorry for her, reproached her, got angry at us, got jealous. I don't remember him ever coming to see me and Mum. And we started to visit them rarely, only on family holidays, at which sometimes there were clashes between him and Kolya. Mum suffered, but tried not to show it. Only once, when it was particularly hard for her, she said that

page203

she wants to part with Alexander Alexeyevich. A serious obstacle to this was the flat issue. The separation entailed exchanging the flat, which was long and complicated. We suggested that Mum should give Alexander Alekseevich our small two-room flat and that we should move in with her. Fortunately this did not happen. Slowly, somehow, everything went back to normal.

Changes in the country and in life

Things were going well for my mother at work. There is no list of commendations for "valorous work" in her work record book. Among them, there was a medal "For Valor in Labor", a sign "Winner of Socialist Competition", a bronze medal of VDNH. She was especially proud of the title of "Honoured Worker of Culture", awarded in 1981, and the "Badge of Honour" awarded in 1983. Mother began to travel abroad on business trips. An unspoken gender principle applied to international exchange between journals. If a woman came to Agitator from Poland, Bulgaria or any other journal, she had to accompany her to Moscow and then pay a return visit. Apart from the technical support staff, Mum was the only woman at the Agitator. She was about 45 when she first went abroad. It was Poland, then Bulgaria and Hungary. Despite the formal partisan nature of the trips, Mum made new friends, a Polish woman Kristina and a Bulgarian woman Penka. The correspondence with Kristina from Warsaw continued for many years. The last letters came when they were both retired and Christina was seriously ill. At Penka's house in Sofia, Kolya and I stayed once when we were travelling in Bulgaria. Penka admired Mum and called her 'the charmer'.

page204

When my mother turned 60, she started talking about retirement. She began to have health problems and found it hard to walk. Every year we persuaded her to go on holiday to a sanatorium, but she categorically refused, resting only in the countryside. It was difficult to give up her job, not only because of the money, but also because of the fear of being left without work and without communication, but Mum decided to do it, only perestroika was underway in 1988. "Agitator" had not long to live, but nobody guessed it then.

Life was changing rapidly in the country. People were reconsidering the events of Soviet history and a new wave of de-Stalinization was beginning. In 1989, as soon as the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet "On Additional Measures for Restoration of Justice to Victims of Repression in the 30s-40s and early 50s" was issued, my mother filed an application for the rehabilitation of my father. The stigma of being an enemy of the people was removed from Vasily Panfilovich, and mother and Aunt Shura were recognised as victims of Stalinist repression because they had been deprived of their father at a young age. Along with a personal certificate.

page205

In addition to her status as a pensioner received for her long-term work for a party magazine, my mother was given a certificate as a victim of political repression by the very party she had worked for all her life. Both statuses gave her some benefits.

When my mother retired, she made plans for how she would help me around the house, cook soup for us, and even go through buckwheat grits. Of course, I didn't believe it for a second, but I was glad my mother was finally living for herself. Her joy was short-lived. The next year she was offered a job in the editorial department of the newly created Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR. Fantasies about soup and buckwheat were instantly forgotten. Mother began to edit the congress transcripts and felt herself in the thick of things. It was a time when parliament was still a place for discussion, when meetings of the congress were broadcast on TV and deputies were known by sight. Transcripts of the sessions were prepared for publication at short notice and the editors' working hours were irregular. Mum did not complain, she enjoyed doing the job. It all came to an end in September 1993, due to well-known historical events. In January 1994 Alexander died. He had been seriously ill for the last years of his life - ulcer, asthma, diseased lungs, problems with his legs, in short, a whole bunch of ailments. Already withdrawn, he withdrew into himself. He was happy with his cat Carrot-top, who was allowed everything. It was not easy for me to hold a conversation with him; perhaps it was different with my mother. Many years later, going through my mother's archives, I found a dacha diary and memories of Alexander Alekseevich, which he had written when he was already ill. Mum was very distressed when he was gone. Mother was left alone at the age of 69. She still had strength, she came to visit us, went to the cemetery, met with friends. From May we started dreaming of moving to the dacha, waiting for the warm weather to set in, for the house to warm up. In June we moved her and Ryzhyk to Veliaminovo. Zoenka (Aunt Zoya, Zoya Nikolaevna),

page206

her closest friend sold her house in the same village and they settled together. We used to visit them (probably less often than they wanted) and bring them groceries.

The last years

Year by year, my mother grew weaker and weaker. A succession of illnesses set in. At 7 a.m. my mother called to say that she was having a heart attack and the ambulance was taking her to hospital. I had a lecture first thing in the morning, no one to replace me. I read it automatically and rushed to the hospital. It was a city hospital in Fili. I was not allowed into the intensive care unit, I was only able to talk to the doctor, who said that the heart attack was extensive and the situation was very serious. I could find out about her condition over the phone, so I had to wait and hope. When I called the next day, I was told that my mother had been transferred to a normal ward for her infraction in the intensive care unit. It turned out that when they took her away from home, she had hidden cigarettes in her dressing gown pocket and in intensive care she got up and tried to go out for a smoke. There were eight people in the ward, three of whom were bedridden. I came every day and stayed with my mother until evening. The attending doctor said that if she smoked she would die. Neither that nor my persuasions and pleas had any effect, no remedy for nicotine addiction worked. The addiction was stronger than the desire to live. My mother would resort to tricks, asking to be taken to the toilet as she was supposedly unable to use the ship. I gave in to her entreaties, we crawled to the toilet and the smell of smoke wafted from the stall. It was a nightmarish three weeks. And yet she survived! Then there was lung cancer, which somehow miraculously disappeared. At the time, such diagnoses were hidden from patients and only reported to relatives. When she was discharged from Volyn Hospital

page207

the doctor told me that a lung operation would not be possible, incase it caused further tumour growth. There is no other treatment available. In general, she will live as long as she can. Mum didn't want to move in with us and Auntie Shura came to stay with her. I tried to find the strength not to cry in front of my mother and looked for doctors who could help her. We took her to consult with doctors who offered their own method of treating cancer, under some invented pretext. This methodology included daily dousing with cold water, to which my mother only laughed. This went on for about a month. Then a miracle happened. My mother had an X-ray at the clinic and it was discovered that there was no tumour.

page208

Then there was a fracture of the neck of the femur. My mother had osteoporosis and often broke her arms, legs and ribs. After her femoral neck fracture, she was in danger of becoming bedridden. But she was lucky, she had an operation straight away and was able to walk. She left the hospital on crutches, but refused to move in with Carrot-top and me, wanting to go home. She wanted to do everything herself. When I went to her house to clean it, it turned out that she had already vacuumed while sitting on a chair. By the summer she was already walking around with a stick and started asking to go to the cottage. It was her last summer. The hardest part was seeing my mother go, and feeling powerless to hold her back. She always greeted me with a smile, dressed up, didn't complain, rarely talked about illness. The last time she came to visit us was on December 15, when my husband and I celebrated our 30th wedding anniversary. She sat with the guests at the table and made a toast. She didn't visit us on New Year's Eve, she stayed home alone, but a neighbour she was friends with invited her to visit. We were at her place on January 1, and on the 7th, my mother called and asked me to come. She had fallen ill, could hardly get out of bed, hardly ate anything, spoke little. The doctor, who had treated her for many years and was very good to her, suggested she had a stroke and said she needed to go to hospital, they could help. Kolya and I packed her things, helped her get dressed and walked to the car. I could have gone with her, but I decided that I should go back and clean the flat and go to the hospital the next day. My mother didn't say anything, just looked at me in silence. We never saw each other again. My mother was put in the intensive care unit, and no visitors were allowed there, neither children nor parents, no matter what condition the patient was in. Such an inhuman order existed then. I called the doctor every day, I was told that the treatment was going on, in a few days she would be transferred to a regular ward where visits were allowed. When I asked if my mother asked for permission to smoke, I was told no, I realised

page209

with Zoya Nikolaevna Yakhontova, 2001.

things were really bad. I decided to go to the hospital, to bribe the doctors and to get a chance to see my mother. But it was too late. In the early hours of 16 January 2002, I received a message from the hospital that my mother had passed away. She was 76 years old. The cause of death was listed on the death certificate as heart and lung failure. Mum is buried in the Vvedenskoye cemetery next to her grandmother, older sister Marusya and nephew Lyova.

Mama was a bright, easy-going, infinitely kind person. She did not like to argue, but she had strong principles in life and always did what she thought was right. I don't remember her ever quarreling with anyone or scolding me, although there was plenty to quarrel. I always knew that no matter what happened, she was on my side. Her love is my support in life.

page210

School and Technical School

Rostik, as everyone close to me called my dad, was born in Arkhangelsk on 12 October 1915. He went to school in Moscow, where his family had moved in 1921. His school years coincided with the time of searching for new teaching methods and pedagogical experiments. The new curriculum adopted in 1923 introduced a complex method of teaching, which denied systematic study of disciplines. The first stage school had three sections of study: 'Labour', 'Society' and 'Nature'. Teaching of arithmetic and Russian as separate subjects was abolished, and the learning of reading, writing, counting and measuring was to be merged with the study of real phenomena. Tuition fees were introduced. Fortunately, the teachers' children were exempt from it, otherwise my grandparents would not have been able to educate their four sons. The environment in which Dad grew up compensated for the vicissitudes of school teaching. Not only my parents, but also my neighbours were teachers of the old, pre-revolutionary school system, of my older brothers some were studying, at technical school, some at university, and there was a good library at home. The boys next door were all the children of school staff. The influence of school manifested itself in a keen interest in politics and social disciplines. According to family stories, at home above his desk Rostik hung a poster "Young Bolshevik's Corner". Peter Osipovich wrote to his son Seva "He is not, after all, an engineer, not inclined to technical disciplines, but more of a humanist. He has always been fond of diamathism and Leninism,"

page211

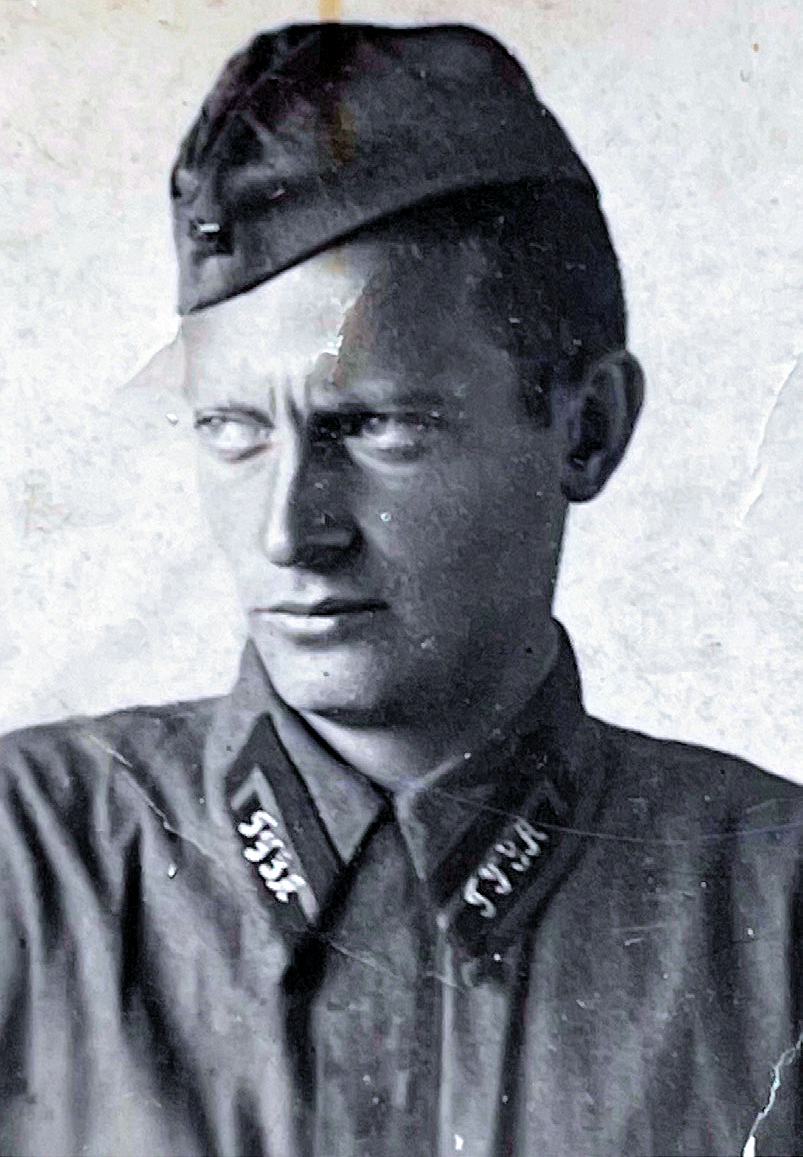

Rostislav Petrovich Dadykin

However, despite his inclination towards the humanities, after completing his seven-year schooling in 1930. Rostik enrolled at the Lenin Polytechnic in Moscow. He was allocated to the Moscow Autogenous Plant, where he worked as a technician from 1934 to 1936. It was at that time that he published his first article in the plant's newspaper which he kept in his archives. The article, in which he criticized the foreman for excessively restricting the independence of young technicians, was signed with the ridiculous pseudonym of Malashkin. I do not know whether the pseudonym was disclosed or whether this criticism had any effect on the author.

The Autogenous profession was in high demand, In a letter that Peter wrote to his son "I often had to go on business trips and the pay was good". In November 1936, Rostik has been on a business trip to Donbass for almost two months. Now he is working in Moscow, but he will have to go again soon.

page212

IFLI

Rostislav entered the History Department of the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History (MIFLI or IFLI) in 1936. It was created in 1931 on the basis of departments and faculties of Moscow State University. According to Liliana Lungina, who had studied at the IFLI since 1938, it was "such an elitist educational institution of the Pushkin Lyceum type created by the Soviet power at a time when it became clear that highly educated people were needed for relations with foreign states " . It is enough to name the professors who worked at the IFLI to appreciate the level of their teaching. They were M.V. Alpatov, V.N. Lazarev, A.V. Artsikhovsky, K.V. Bazilevich, S.V. Bakhrushin, S.D. Skazkin, M.N. Tikhomirov and many others. To enter the IFLI one had to pass ten examinations, including physics, chemistry and mathematics. For a person who had worked in a factory for two years, this was more difficult than for guys who had just finished ten years of schooling. Unfortunately, I never questioned my father about his student years, but I can gauge the atmosphere from the memories of IFLI graduates

page213

that reigned in this university. From the memoirs of the philologist N.I. Balashov: "Study was a passion. There was a rush to learn and to think. We sat until closing time in various libraries in Moscow and in the offices of the IFLI.

Papa studies mostly excellent and good; his record book gives satisfactory marks only in military studies and in source studies

From M.N. Tikhomirov. He joined the Komsomol at the age of 21 at the IFLI. This is rather late for a man who aspired to a career in public work. Rather, he associated his future with science and teaching. In his final year he was working as a history teacher in the ninth form at school no. 103 at the same time as his studies. Graduation coincided with the outbreak of war. In June 1941 the last exams were passed, a diploma was received, and in July Rostislav was called up into the army.

page214

War

His army service was not at all what one would have expected. For a historian with a university degree, the road was straight to an officer training course for political officers. And so it was at first. As his grandmother wrote in one of her letters, Rostik was sent to a course in the Gorky region. Exactly what happened to him on the course is unknown, but he was a common soldier during the whole war, he was in artillery and motor reconnaissance. Why did he not become an officer? Here is the version I heard from my mother, who was told to her by my father. Grandma sent Rostik a parcel wrapped in a German newspaper. Before the war, when the Soviet non-aggression and friendship treaties with Germany were in force, German newspapers were sold in Moscow, and Grandma, a German language teacher, was buying them. Wrapping up a parcel, my grandmother took one of the old newspapers without looking, and thus decided my son's military fate. He was expelled from the courses, and in August 1942 he was sent to the Kalinin front as a private. Judging by his father's Red Army service record book, which was issued before his discharge in October 1945, one could trace the course of his front-line fate. He got to the first battalion of 47th guards artillery regiment in a rank of guards Red Army soldier. The post is written in abbreviated form "Ord. commander". We can assume,

page215

that he was the commander's lieutenant, but it is unlikely that a Muscovite with a college degree was suitable for the position.

Rostislav found himself on the Kalinin front during the fighting near Rzhev, which went down in history as the Battle of Rzhev, one of the bloodiest battles of the Great Patriotic War. Since March, 1943 he fought on the Second Baltic, since September, 1944, on the First Baltic, since February, 1945, on the Second Byelorussian front. In March 1944 he joined the motorized reconnaissance, and in the last year of the war he became a political instructor (company or battalion Komsomtag). His last position in the army sounds rather strange - political group leader. Apparently, he conducted political training with groups of soldiers. He was never wounded, went to hospital only once due to illness. During the war he received two medals, both in 1945 - "For the Capture of Koenigsberg" and "For Victory over Germany" and thanks for his participation in the battles. Here is the enumeration of these fights in 1943-1945: liquidation of German summer offensive in July 1943. ; liberation of Belgorod, Kharkov, Znamenka, Kirovograd, Zvenigorod, Shpola, the end of Korsun-Shevchenko operation, the breakthrough of German defence at Uman, reaching the state frontier with Romania, the liberation of Borisov, Minsk, Molodechno, Vilnius, breakthrough of German defences west of Šiauliai, access to the Baltic Sea near Kretinga, liberation of Mlava, Dzialdovo, Ploňsk, invasion of East Prussia, liberation of Gdańsk.

Graduate school. Marriage

In November 1945 my father was demobilized and was immediately hired as an instructor for propaganda at the Moscow City Committee of the Komsomol. In the summer of 1946 he went to the graduate school of the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Here he also joined the Party.

page216

Since the IMEL postgraduate school was closed in the spring of 1948, the postgraduate students were transferred to the Institute of the History of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, in the History of Soviet Society sector. The next two decades of his short life were associated with this institute.

Simultaneously with his postgraduate studies, in May 1947 Rostislav got a job in the journal of the Central Committee of the Komsomol "Young Bolshevik" as the head of the Marxist-Leninist theory, and then he was promoted to the post of deputy head of the department. He met Nina Boykova, who soon became his wife, in the magazine's editorial office. She was 23 years old, he was 33. She was beautiful, cheerful and sociable. He was a tall interesting man, "promising" as they would say now. I think girls in those post-war years did not pass him by. As my mother told me, their romance was short. After a month of courting Rostik proposed, they got married on October 24, 1948, and Nina moved to Glazovsky Lane. It's hard to say what was more in this impetuous marriage, the sudden outburst of love or the desire to have a family of their own and children. It all worked out. On August 26, 1949 A daughter was born in Grauermann's maternity hospital, which was the closest to Glazovsky Lane.

Daddy really wanted a son. When he found out that a girl was born, his first reaction was:

page217

"Well, it can't be helped. But that didn't stop him from loving me. While my mother was pregnant, they called the baby 'the little man'. It became my childhood family nickname. Even in my eighteenth birthday card, alas the last one written by Dad, he refers to me as "my darling little man".

As a child I saw my dad working from home a lot more than I saw my mum going to work every day. He had a large desk covered with a green cloth and a lamp with a green glass shade. The desk was still my grandfather's, massive, oak with carved round legs. And the lamp, also antique, with a round metal base standing on three sphinxes. The desk was always littered with papers, and Dad got very angry when Mum or our housekeeper Natasha tried to wipe the dust off it and tidy it up. To finish his dissertation, Dad had to quit his job at the magazine in August 1950. When the text was already written, he was hired as acting editor-in-chief of Voprosy Istorii, where he worked from February 1951 to April 1952.

Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In May 1951 he defended his thesis on "The beginning of mass socialist competition in industry", and in January 1952 he joined the Institute of History as a junior research associate of the socialist period sector. In 1954 he was transferred to the World History section and a year later, in September 1955, he became a senior fellow. In January 1958, when work on "World History" was completed, he returned to the department of the history of Soviet society, and from January 1959 he became head of the group on the history of the Soviet working class and the industry.

page218

The last entry on his personnel sheet was made on 8 July 1968: "Expelled due to death". His academic career was short, but he managed to do a lot. He published a monograph on the subject of his dissertation, was one of the authors and editors of collective works such as the ninth volume of 'World History', the eighth volume of 'The History of the USSR', 'The USSR in the Period of National Economy Restoration', 'The Contemporary History of the International Labor Movement', 'The Formation and Development of the Soviet Working Class (1917-1961)'. Many of works on the history of the working class of the Union republics, remain in his library with notes of thanks for his help in editing. In the last years of his life he worked on his doctoral dissertation "The Working Class of the USSR in the Years of Socialist Reconstruction of the National Economy. 1928- 1937". The chapter he managed to finish was published after his death. Now, thirty years after the collapse of the USSR, it is clear that his work has not outlived its time, nor, for that matter, .

page219

have most of the Soviet historiography. My father honestly did his job within the established rules and in accordance with an ideology which he wholeheartedly embraced. He was the only one in his family to choose a profession involving the ideological service of power, which his parents could only treat as a necessary evil. He never spoke of politics with me, and never once mentioned Stalin's name in any context. I remember adult conversations falling silent when I entered the room, and the phrase, "This is not a telephone conversation. I asked my parents about Stalin myself when I went to school. It was 1956. It turned out that half the class had two portraits in their textbooks, of Lenin and Stalin, and the other half had only Lenin.

Dad did not influence my choice of department, but when in the second year I had to choose my future specialization, he advised me to go to the department of Soviet history to study cultural history. I took this advice as a testament. He was ill and I knew that he had cancer. We were living separately at the time, Dad had another family.

page220

Divorce and remarriage

I was about 11 or 12 years old when my parents told me they were getting a divorce. The news came out of the blue. I'd never seen them fight before. And suddenly! The world was falling apart I was playing in the yard and ran home for a minute to get something. I was in a big hurry to get back, but my parents were unaccustomedly serious about asking me to stick around. They need to talk to me. And what did they say? They are getting a divorce and ask me who I want to stay with. I love them both and there is no choice. I keep quiet. They keep talking quietly to each other and I realise that they have already decided everything for me, that I am going to live with my mum and my dad agrees. Then there were several years of a nightmare that is hard to remember. Dad's desk and all his books were moved to Grandma's former room, and my mother and me to the other two. The door between the adjoining rooms was closed by a wardrobe. Aunt Marusya, mother's older sister, and numerous friends would come and try to reconcile them. Peace was restored for a while. The furniture moved again, the closed door was opened. But it wasn't for long. Everything repeated itself: rearranged furniture, closed doors, endless adult conversations. Mum was ill. She lost a terrible amount of weight. I remember she put on my pioneer uniform, which fit her. She had a nervous breakdown. My aunt said my father wanted to send her to a psychiatric hospital. This is probably the scene that sticks in my memory - Dad says something to me, probably about Mum, and I shout: "I hate you!" Mum had to have an operation to remove her thyroid gland, but was offered an alternative treatment - to take radioactive iodine. And she agreed.

page221

When my parents finally divorced, things calmed down. The idea of divorce as the inevitable and correct outcome of married life had been ingrained in my mind for a long time. Even as a fully-grown girl, what they call a "marriageable girl", I believed that one should not get married for life.

The divorce happened when my father met Nadezhda Mikhailovna and moved in with her. The initiator of the divorce, the reasons for which I can only guess, was originally Dad. But it must have been difficult for him to take the decisive step when everyone around him was urging him to keep the family together. Especially since there was nowhere to go and it would have been difficult and time-consuming to exchange our rooms. My relationship with him quickly improved. He did not immediately introduce me to Nadezhda Mikhailovna, for a while he took me to dinner at the House of Scientists on Kropotkinskaya (now Prechistenka) or to Prague. Then he started inviting me home to his new family. I had no prejudice against Dad's new wife; on the contrary, I was grateful that the long nightmare of divorce was over.

I met Nadezhda Mikhailovna's youngest daughter, Nina, her husband, Tolya, and their two-year-old son, Dimochka. Nadezhda Mikhailovna's eldest daughter, Luda, was also married and lived separately. They were all very nice nice nice people. I think Papa was happy in his new family.

Illness. The last year.

But it didn't last long. In the summer of 1967 Dad became ill, some kind of gallbladder problem. In September he had an operation. When I called Nadezhda Mikhailovna to inquire about the results, she asked me to come. It turned out that Dad had bile duct cancer, inoperable. Medicine was powerless.

page222

Nadezhda Mikhailovna found some healers who prescribed him an unusual treatment. He had to look into the eyes of a live pike. As absurd as the recommendation seemed, Dad, being quite a rational person, agreed. He and Nadezhda Mikhailovna went to Tarusa, rented a cottage there and arranged with a fisherman to supply live pike. They told me that they wanted to have a little break in nature. I found out about the pike when I came to Tarusa to visit my father. they told me that, the whites of his eyes became noticeably lighter, although the yellowing did not go away completely. And the pike had turned yellow after the session.

On the healers' advice my father began to follow a special diet. I do not remember what it consisted of. I remember only that instead of yeast bread he ate matzah, for which Nadezhda Mikhailovna went to synagogue. But nothing helped. He continued to grow thin, yellow and weak. The only thing in which doctors' predictions were not justified, he had no pains, which cancer patients usually have.

In the last year of his life, Dad's relationship with his older brothers, which had deteriorated after his grandmother's death because of the "housing problem", began to improve. I actually reacquainted myself with Uncle Vanya and Uncle Seva, whom I had not seen since early childhood. Dad invited me to dinner one night, when he was supposed to have Uncle Vanya and Tatyana Borisovna over.

page223

A funny scene occurred during dinner. My dad asked me what I was going to drink. I was 18 years old, I felt very grown-up, and I was not restricted in my choices at home. I calmly replied that I would probably have some cognac. Everyone laughed, because they weren't expecting such an answer. Dad was shocked: "How? Are you allowed to drink cognac at home?"

Before the new year, Dad was still working, going to the institute. He did not know that he had cancer, at that time such a diagnosis was concealed from the sick. He believed in a cure. In the spring, when Dad was no longer going out of the house, he asked me to go to the institute to deposit books in the library. But neither then, nor afterwards in May, when Nadezhda Mikhailovna left on a business trip and I stayed with him for a week, did he have any faith in his recovery. He hardly got up, sat on the sofa, terribly thin, with a swollen belly, and said he would get better. What was it? The psychological defence that cancer patients have in their final stages? Or was he sparing me? God knows. Luckily he wasn't in pain, and that I was able to spend the week with him. I waited for him to tell me something important while we were alone. Once he talked about my mother, wanting to explain why he couldn't live with her. But I wouldn't listen.

In June, Nadezhda Mikhailovna rented a dacha in Klyazma and moved Dad there. I was to be sent to the construction camp for a month, but in order not to be away from Moscow for a long time, I replaced the construction camp with a ten-day trip with a propaganda team. The plan was that, on my return, I would stay at their dacha. On 7 July 1968, when I was in Western Ukraine, I learned that my father had died. I went straight from the train to the funeral. He was cremated in the Donskoye crematorium, and the urn was buried there. I didn't see Nadezhda Mikhailovna for some time. And once I met her by chance in the street. We exchanged telephone numbers, and I started to call her and visit her from time to time. She lived many more years after Dad's death, even got married again, but she kept very fond memories

page224

of Dad and was always happy to receive my calls and our meetings. When I suggested that Dad's urn be moved from the Donskoye crematorium to the Vvedenskoye cemetery, where his mother is buried, she asked me not to do it before she died. Her parents were buried in the crematorium cemetery, and when visiting their graves, she would also visit Dad. When she passed away in 2003, we moved Dad's urn to Grandma's grave.

page225

Our flat and its inhabitants

We lived on the second floor of flat 3, building 10 on Glazovsky Lane. More precisely, it was the second and a half floor, because there was also a semi-basement in the house, where people also lived. Grandparents and four sons settled in that flat in the early 1920s, when they moved from Arkhangelsk to Moscow. It was service housing for the teachers of the Rukavishnikov Orphanage, built before the revolution. Initially the house had two floors but in the mid 1930s two more floors were added. The flat had five rooms, three of which were occupied by my grandparents' family and two by neighbours.

The flat I spent my childhood in was strange, unlike any other flat I had ever lived in or visited. Like Pinocchio, who suddenly found a secret door behind a painted hearth, as a child I would occasionally discover that behind a curtain or behind a cupboard there were some doors leading nowhere. All five rooms in the flat were passageways, and the biggest room had four doors. It gave us access to another room, a corridor, a hallway, and the neighbours. The door to the neighbours was always closed, while the others were opened or locked depending on the changes in our family composition.

page226

The time came and Peter Osipovich and Glafira Ivanovna's sons married and had children. Vanya and Lina separated from their parents in 1933 and rented a room. In 1934, after three years in Magadan, Seva returned with Lelya and little Ninotchka. It became crowded. Peter Osipovich with Glafira Ivanovna in one room, Pavlik and Rostik in another, the third room was given to a young family. Seva earned good money in Kolyma, and in 1936 it gave him the opportunity to join the construction cooperative. They promised the first 50 flats would be ready in the spring of 1937. Only in 1954 Sergey, Lelya and their two children (their second daughter Irina was born in 1944) managed to get a flat on Peschanaya Street. Of our three rooms, one was occupied by my grandmother, the other by my mother and father and the third by my father's brother Uncle Seva with his wife and two daughters, Nina and Ira. From the hallway there was an exit to the front staircase that led to the street, but it was closed, and everyone went through the back door, which went into the courtyard. This was common in Moscow houses. Shelves were made in the doorway of the hallway and covered with a curtain. There was a windowless room where Natasha slept on a chest of drawers in a nook behind a wardrobe. When Seva and his family moved to a new flat, Natasha and I were moved into his room. The vestibule became an anteroom, Natasha now slept on a small sofa instead of a chest. And Grandma's room was no longer a passageway. For my mother and me, this flat was our first home. I lived in that flat for 16 years, Mum 17, Dad about 40. We had no bathroom and no hot water, there were occasional bedbug infestations, but we had lovely neighbours, a cosy Moscow courtyard. My happy childhood was spent here. I still remember where everything stood and hung, I remember our yard, our girlfriends, our neighbours.

page227

Natasha (Natalya Petrovna Chihireva)

Natasha lived in our family for several years as a housekeeper, but to me she was like a grandmother. She was always there for me. She lived with us, ran the household, went shopping, cooked dinner, baked cakes for Easter, braided my braids, and got me ready for school. She was small and round, with a kind, gentle face, riddled with pockmarks. I loved to sneak into her cozy little corner behind the wardrobe, where she slept on a chest, and she would tell me stories. In the summer I was usually sent to the country house with my mother's sister Aunt Shura and my cousins Misha and Ira, while Natasha went on holiday to her home country. Parting with Natasha left me in tears. One summer, I was 5 years old, she took me to Tetyushi. It was a small Tatar town on the high bank of the Volga River. The only thing I remember was the long, steep wooden staircase leading up to the river. (This staircase is mentioned in I. Ilf's "Notebooks". But I found out about it many years later). Natasha must have been from this town. How old was she? I know that she retired and left us when I was about 10 years old, so I can guess that in 1959-1960 she was at least 55. Natasha was

page228

a professional housekeeper. As a child she had contracted smallpox, which left mark on her face. Perhaps that is why, without any expectation of marriage, she went to Moscow and worked as a housekeeper for different families, all her life. She came into our family from my father's brother Uncle Seva, who lived with us in the same flat, and even earlier she worked for T.M. Zueva, Minister of Culture of the RSFSR. Natasha often remembered her daughter Belochka and held her up as an example to me. Natasha had an elder sister who lived near Astrakhan, near the Orangery fish processing plant. From there Natasha often received parcels - one-litre glass jars of black caviar, not factory-packaged. Back then caviar did not seem like a super delicacy. When Natasha retired, she went to live with her sister, but our connection was not cut off. She corresponded with my mother, and in 1969 I went to visit her. My first impression of meeting her at the train station in Astrakhan was that Natasha turned out to be very small in stature, but her appearance hardly changed. She lived alone in the cottage left behind by her sister's death. I spent about a week with her. I never saw her again. I don't know when she died.

Anna Osipovna and Alexandra Osipovna Sokolova

At that time, our neighbours were two lovely old women former teachers - sisters Anna Osipovna and Alexandra Osipovna Sokolov and Georgy Nikolaevich Sibiryakov, husband of their younger sister Nina Osipovna, who herself lived mostly with her daughter. The elder Anna Osipovna was quite decrepit, she did not go out, and the path from her room to the kitchen was not easy for her. She usually stopped in the doorway to take a breather and when traditionally asked how she was feeling, answered that she was in pain. I, a little girl, didn't understand how she could be in pain

page229

all at once, and asked, "Do your legs hurt? And your arms? And your head hurts?" Instead of saying, "Leave me alone, silly girl," Anna Osipovna would patiently answer my questions in the affirmative. I kept up: "Is there anything that doesn't hurt?", Anna Osipovna thought for a second, then touched the tip of my nose and said: "Only here it doesn't hurt."

All their household chores fell to their younger sister, Alexandra Osipovna, who was little tougher. She did the shopping, cooked the meals and looked after her older sister. One day I had to sew on something, a button or a collar that had come undone. Natasha wasn't at home, so I went to Alexandra Osipovna. She gladly agreed and said she would teach me how to do it. While she went to get sewing materials, I ran away and hid in the wardrobe. I still remember with shame how she walked around our rooms, looking for me and calling out for me, but I never came out. In spite of all my foolish childish antics, they loved me and often invited me to their house for tea. They had a black cat called Pan, beautifully bound books (the Brockhaus and Efron dictionary), and a picture of Leo Tolstoy on the desk.

Georgi Nikolaevich lived with them in the passage room. His passion was travelling in the mountains. Throughout the year he put aside money from his pension to save for a trip to Kyrgyzstan or the Caucasus. There was almost nothing left for food, so he ate bread and tea. He never said he was hungry and never asked for anything, but when Aleksandra Osipovna or Natasha offered a leftover bowl of soup or a second meal, he gladly agreed. He was terribly thin, shaved his head and wore a beard. I don't know if this is true, but the adults said that one day an artist in the street offered Georgi Nikolaevich the chance to pose for a picture of the Rising in Buchenwald, but he declined. When Georgi Nikolaevich was unable to walk in the mountains, life lost its meaning for him and he began to talk about suicide. Next to the kitchen sink he hung a piece of paper with the inscription:

page230

"The traveller who walks the mountain path over the abyss, remember that you are a tear on your eyelash". That was what he was going to do - go to the mountains and not come back. A few years later he tried to carry out the plan, though not in the mountains, but in a flat. At that time Anna Osipovna and Alexandra Osipovna were no longer in the world, my mother and I moved to University Avenue, my father was not at home. No one heard Nina Osipovna's screams, in front of whom it was happening. Fortunately, the bad show ended safely. The rope broke and he survived. Georgy Nikolayevich was taken to the police station and was required to give a written undertaking not to repeat such attempts. He himself was glad to be alive. When he came to visit my mother and I at Universitetsky Avenue, he would walk (ten kilometres one way!) all the way, he would tell me with apparent pleasure in detail how he hung himself and recite a poem he had written, which began with the words: "In the afterlife I staggered". The obsessive thought of suicide would not leave him. He said that the written commitment he gave to the police applied only to the place of action, his flat, and that there were many other places where it was possible to end one's life. As far as I know, he died naturally.

page231

⦿ Next Page