page231

The Boykows. My mother's sisters and brother

The kinsmen on my mother's side were very friendly with each other. It was one big family, including siblings and cousins. They were all born in the remote village of Zabolotye in the forests in the west of the Tver region, from which they strove with all their might to escape, and then remembered fondly.

page232

Life scattered them to different cities, but they were always in touch and, if anything, rushed to each other's aid.

Only my mother's sisters and brothers, the children of Maria Yegorovna and Vasily Panfilovich Boykov, will be discussed here. The closest cousins were the children of Semyon Panfilovich, my grandfather's brother, Aunt Katya (Ekaterina Semyonovna), Aunt Zhenya (Eugenia Semyonovna), and Uncle Vanya (Ivan Semyonovich). They were left without a father at an early age and my grandfather helped them. Uncle Vanya did not live long enough to reach 100 years of age. He was the last of my relatives to tell me how my grandfather was raised.

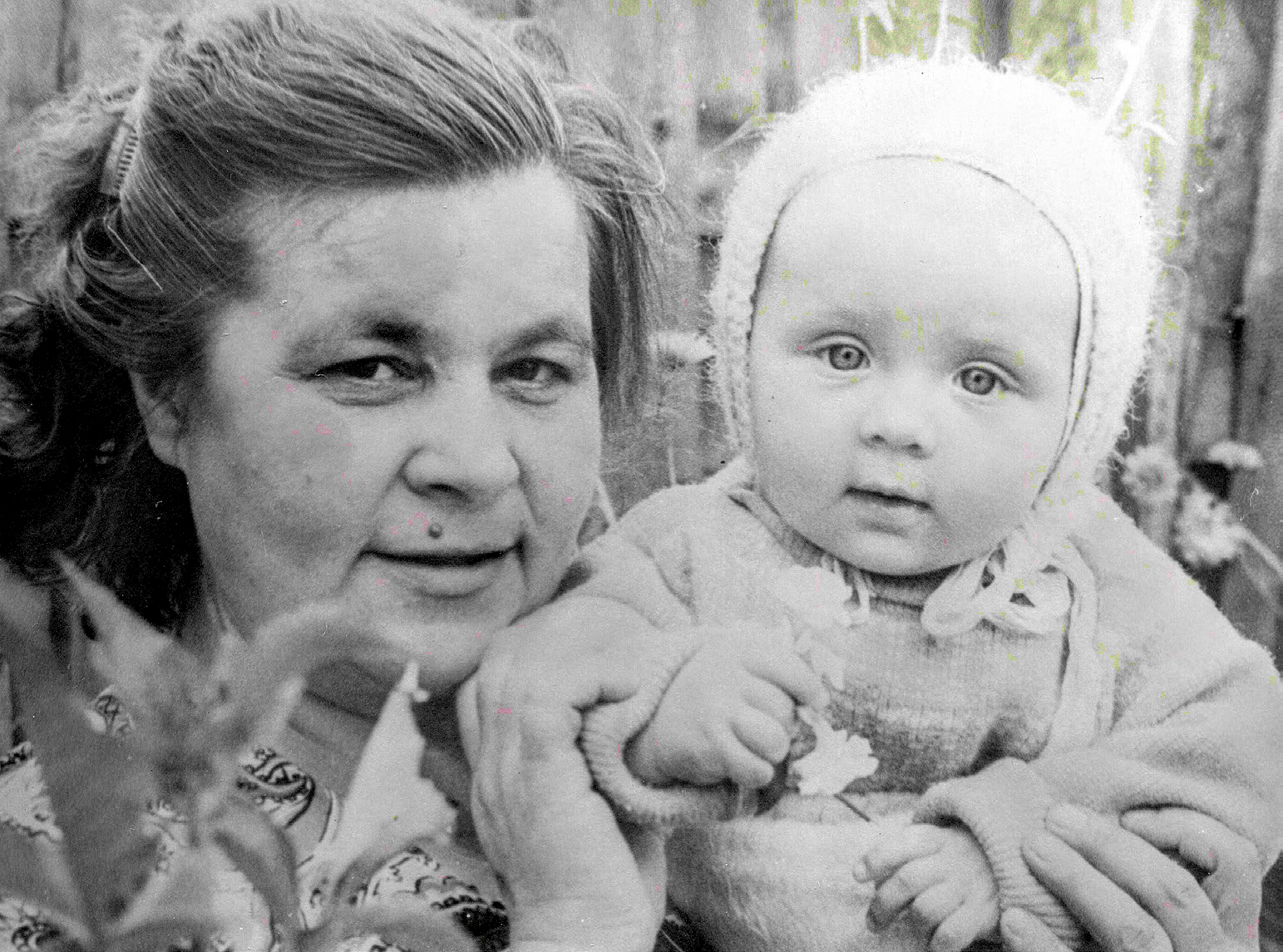

Maria Vasilievna Shabokhina

My sisters called her Marusya, Manya, Manechka, I called her Aunt Marusya, Auntie, and in her old age she became Grandma Mania to everyone. She was the eldest in the family, the connecting link for the relatives. She loved us all, took an interest in our affairs, helped us all.

Youth

Maria was born on March 26, 1909 in Zabolotye. It is written in her labour book that she had a primary education, but according to the story of Baba Mania herself, she only studied at school for two years. As the eldest she had to help her mother with the housework and look after the children. At 16 Marusya married Kostya, who was two years her senior. At 17 she gave birth to her son Lyov. Lyova was only a year younger than Marusya's younger sister Nina, my mother. Family life with Kostya did not work out. According to Baba Mania's story, he had a fling, and she could not forgive the infidelity.

page233

Marusya was attractive, cheerful, sociable and sharp on the tongue. She was courted by the chairman of the village council, Fedor Bogdanov, a 30-year-old bachelor. She joined the Komsomol under his influence rather than by conviction, and when collectivisation began she joined the commune. Maroussa didn't like life in the commune and didn't stay there for long. The commune collapsed, the communes were replaced with collective farms. Together with Bogdanov and other activists Marusya agitated fellow-villagers to join the collective farm.

In the autumn of 1929 mass forced collectivisation began. The authorities turned from agitation to financial pressure on those who refused to join the collective farms, and to criminal prosecution. When this wave reached Zabolotya, Marusya ran to her father to warn him that if he did not apply to join the collective farm, he would be dispossessed. Vasily Panfilovich did not listen to his daughter.

Officer's Wife

Marusya married for the second time in 1931 to Alexei Shabokhin. He served in the army with the rank of military officer of the 2nd rank. According to Baba Manya, there was no great love on her part, but Alexei insisted and she agreed. Alexei adopted Lyova, and Lyova and Marusya carried his surname for the rest of their lives. To help her mother, who was left alone with the youngest children after her father's arrest, Marusya took in her sister Shura. Alexey was transferred to Bobruisk, then to Zubtsov, and Marusya followed her husband with Lyova and Shura. In 1936 Alexey was sent on a several-months trip to Spain. She learned of her husband's whereabouts, his shell-shock injury and the Order of the Red Banner only after his return in March 1937. .

page234

After Spain, Alexei was sent to study in Moscow at the Red Army Military Academy of Mechanisation and Motorisation. They were given a room in the Academy's dormitory. Marusya completed a course for a bank teller and joined the workforce in October 1938. On December 30 of the following year she was dismissed for truancy. That was the only disciplinary offence in her service record book. On the other hand, the section on awards and decorations was filled out to the very last line. The next entry in her workbook after her dismissal casts doubt on the absenteeism charge. On 29 December, the day before her truancy at the Pervomaisky District Savings Bank, Marusya had been hired as a supervisor at the Baumansky District Savings Bank. I believe she had moved to a job closer to home but was not let go from her old job. She got a new job and was dismissed from her old job for absenteeism. .

page235

When war broke out, the senior cadets of the Academy were speedily released and sent into the active army. In October 1941, Alexei left for the west and Marusya, Lyova and Shura left for the east. The Academy and family members were evacuated to Tashkent. Marusya was hired as a cashier in the Academy's financial department and in July 1943, she was transferred to the post of treasurer of the financial department. In the summer of 1943, the Academy returned to Moscow. Maria continued to work at the Academy, while Lyov was waiting to be drafted into the army. Alexei and Maria decided to send their son to study at a tank school so that he could become an officer. The school accepted 18-year-olds, and in 1943 Leo was only 17. Alexei arranged with the head of Samarkand Tank School, a good friend of his, that Lyov would be enrolled in 1944, when training had already begun.

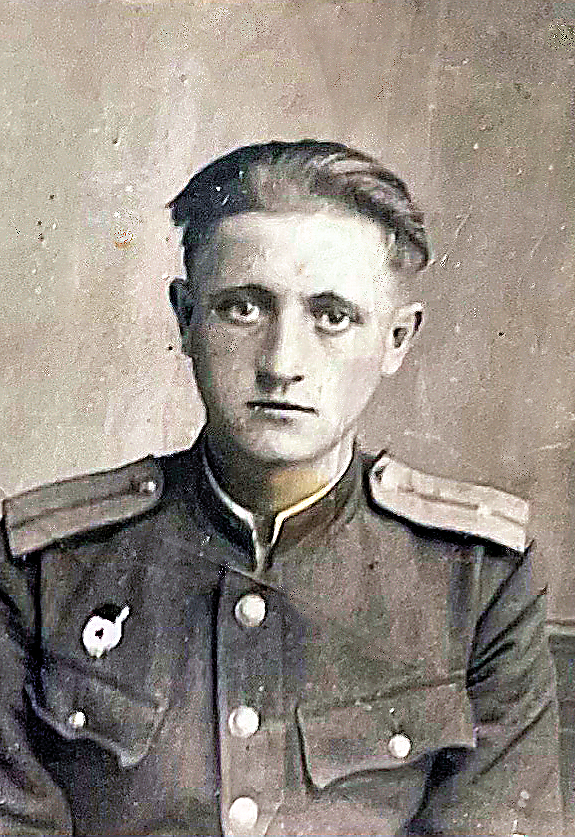

Son

In February 1944 Lyov became a cadet. The first months were the hardest for him. He had to get used to the army discipline and catch up on missed work. Letters from Samarkand have survived. He asked for books to be sent to him for lessons. He wrote to Shura that he didn't even think about girls, that all he could think about was how to sleep. Day and night he sat at his books. By May his studies had improved: "Not a single bad or mediocre mark, good and excellent in all subjects. Wanting to join the Komsomol, he asked his mother and father to send him Party references. Lyova was homesick, but did not complain. The exception was a letter of 22 July, in which he wrote that he had been walking barefoot for half a month to all his classes, and asked his mother to send him some boots, a dressing gown and a pair of trousers. A few days later, a correspondent from his company came to Moscow to collect the goods for Lyov. .

page236

What happened to his clothes and shoes? He had written in previous letters that he had received new boots and that the cadets had been promised new uniforms by 1 May. Lyova did not explain this; a comrade who came from Samarkand had to tell me about it. The only thing I can say is that the cadet food ration was in short supply and that Lyov (and probably other cadets, too) were swapping clothes for food in the bazaar.

In November 1944 Lyova took the last state exam at the school. He hoped that before being sent to the active army they would be taken through Moscow and he would be able to call at home. He asked his mother to write in detail about all the news from Moscow, and most importantly, he asked: "Try to get gold epaulettes." The epaulettes had only recently been introduced in the army and the young lieutenant wanted very much to show off in front of his relatives and friends. It is not known, whether Marusya got gold shoulder straps or not, but she managed to see her son before he was sent to the front.

Lyov got to the front in the beginning of 1945. The army was advancing fast, there was no time for letters. A postcard congratulating him on the 8th of March came from Stanislav (Ivano-Frankivsk), the next was from Budapest. On 13 May, Lyov wrote that they were marching through Germany. On 22 July a letter arrived from Vienna. .

page237

War was about to end, but Liova was able to "smell the powder". In one letter he remembers his friend who saved his life, in another he says that the tank had burned out, he had been knocked out by the shell and was in the infirmary. At the end of 1945, Lyov sent a photograph from Romania with the inscription "In Memory of mother from son" as if he had foreshadowed his departure.

After the war

María waited for her son to return home, but in the first year only older children were to be demobilized. Lyov remained to serve in the garrison. In early 1946, thanks to her connections at the Academy, María was able to send a letter to Leo from Moscow. "Mama, what makes you better than anyone else? - My son wrote back, "I am ashamed of my co-workers. He said he could leave at the earliest in three months and asked for a call back to his brother-in-law who saved his life. It is not known exactly when Leova returned to Moscow. It most likely took place in August 1946. On 3 January he was 20 years old. It was on that day, which proved to be a fateful one for him, that he went to Turgunov to visit his grandmother and aunt Vera, but he did not arrive. If it were not for his accident, Liova would be considered missing. His aunt's husband, Peter Louvrevitch, was a local police officer. In his daily report of events he wrote .

page238

A woman said that there was a young man in underwear and no documents near a railway track. Nearby lay a letter that had been thrown away or thrown away by a perpetrator. After reading the letter, Peter Louvrevitch realized it was Lyov. The letter was written by María to her sister Vera. He was buried in Moscow at the Vvedenka Cemetery.

The killer was not found. It was thought to be a deserter who killed Lyov for the sake of military uniforms and documents.

After the war.

María was left alone with her grief. Her husband did not return to her. In the last four years, Alexei stopped writing not only to her but also to his son. This could be explained by the rapid advance of the army, and heavy fighting, but he did not take part in the battles and served as chief of the tank repair plant of the 1st Balkan Front. For three months in school, he has sent his father seven letters, but he has received no answer. Maria and Lyova were worried about Alexei's silence. Lyova wrote to his mother: "I'll have to talk to him like an officer when I finish school. I will settle accounts with him for myself and for you." Alexei only turned up in the spring of 1946. He had an affair with a nurse at the front and she gave birth to a child who was deaf and dumb. Alexei asked for a divorce because he couldn't leave his sick son. Maria didn't write to Leo about it, and the son, sensing something wrong, repeated several times in his letters the question about his father, asking him not to hide anything. The fact that his father had left the family, Lyov only found out after he returned home.

I don't know if Maria told him that Alexei was not his own father. Perhaps she did. I thought it was strange that Lyov went to visit his grandmother on his birthday and didn't celebrate his twentieth birthday at home. When I asked Grandma Manya, .

page239

she said they didn't have the money to invite guests. I can assume there were other reasons too. Alexei was at Lyova's funeral. I think that after the divorce he provided some kind of assistance to his ex-wife. He was quite a wealthy man, finished the war with the rank of Colonel Engineer, continued to serve in the army, and after his retirement he worked as director of the Kharkov tank repair plant.

Maria continued to work at the Academy. In 1948, she was transferred from the position of treasurer of the Finance Department to that of cashier. But she became tired of working with money and asked to be a dispatcher at the motor pool. She worked there until she retired in 1964. As a loner, she was given a nine-metre room on the third floor of a three-room flat. Her neighbours were an elderly, intelligent couple, David Efremovich and Sofia Yakovlevna Rosenblum.

page240

Maria was only 37 when she was divorced, but she never remarried, although there were offers. The suitors were all military, which meant leaving Moscow and moving around the garrisons. It wasn't the capital that kept her going, it was the cemetery where her son lay. She was often there. For many years she had a friend, Lieutenant Colonel Nikolai Nikolaevich Shcherbanenko. He was younger than her, married, and worked at the Academy.

Her family was all of us, sisters, nephews, then our children. The sisters were very friendly. Before the war and in the evacuation Maria's family lived with Shura. After the war, Maria took Nina in, already in Moscow. Her nephew Valera, who studied at the medical institute, lived with Aunt Maroussia for several years. At the first call she went to help, if someone close got ill, if it was necessary to look after the child. The sisters called each other almost every day. When the phone bills came in for calls to Leningrad, where Shura lived, and to Kalinin, where Vera lived, Aunt Marusya sighed heavily, but immediately added: "Well, you can't call from beyond the world. She had many friends. I remember big picnic trips to the forest with the Miroshnikovs and Chernovs. They were a family of officers from the Academy with children about my age. We had no car and they drove trophy cars. The big black car was affectionately called "polecat". The same group once celebrated New Year's Eve with us.

I loved to visit Aunt Marusya, her room seemed unusually cosy to me. My mother and I often went to visit her, and at the same time to wash up. We had no bathroom in Glazovskoe, but Aunt Marusya had a bathroom with a window and a gas boiler. Sometimes I would stay overnight at her place. And then she would take me to work early in the morning and send me to school in a car with a driver who was on the way to some were. She took advantage of her position as a dispatcher. She was treated well and never refused.

page241

Every year, on 3 January and 26 March, we gathered in her little room to celebrate Levin and her birthdays. The table took up the whole length of the room, and the neighbours, who were also at the table, helped with the dishes and chairs.

The later years

As the years passed, there were fewer guests. Friends passed away, neighbours one after another died. Grandma's mother moved into one of their rooms, bigger and with a balcony. And instead of an elderly Jewish couple, a young family with a young child moved in. At first everything was fine, but soon the neighbours got divorced but did not move out. Things got ugly, the husband got drunk, the wife got drunk. It got "fun." We suggested to Baba Mana that she move in with us, and Nina asked her to move in, but she refused. Life was hard for her. She had a small pension She did some knitting as a part-time job. When she was in her sixties, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and her breasts were removed, there was no chemo back then. She survived. As she got older. she had diabetes. Until it was diagnosed and treated, there was fear that it was the end. Baba Mania never complained and seldom asked for anything. Before I went to see her, I always asked her what to bring. The usual answer was: "I've got everything, come and get some pancakes. It was easy to guess that there was nothing in the house apart from flour and milk. She had an easy temperament, I don't remember her being discouraged, as it was hard for her. She used her small pension to pay for her funeral. She was afraid to keep money at home because of her neighbours, and it was hard to go to the bank. My grandmother, chose me as her bank. I kept her money, she gave me instructions on how to bury her. Every time she talked about it, I stopped her because I found it hard to listen and think about her death. And she had a great time.

page242

Years ago, no one ever died from talking about funerals. When colour TVs came along, the coffin savings came in handy. She hesitated for a long time, I persuaded her: "Don't worry, we'll bury you when we have to, just take your time. In autumn 1992, Baba Mania asked me to move her to Nina's. It was painful to watch her go down the stairs, knowing that she would never return home. She did not live with her mother for long. On December 14, 1992, she passed away.

When someone close to you passes away, you often feel guilty about it. This feeling occurred to me at least twice during my grandmother's lifetime. One day we were celebrating the birthday of Leon, her favourite grandson. We called Granny Mania, not thinking how she would get there. She didn't come. Then she said she went out into the street, started catching a car. Whoever stopped, asked too expensive. She went back home. I could have picked her up, but I didn't.

Another incident is related to our trip to Zabolotye. It was in 1990 or 1991. We went with my mother to her hometown and decided not to say anything to Baba Mana. She was already walking badly, not feeling well, which could have made the trip more difficult. When she found out, she was upset. It was the last chance for her to see her home. Besides, it turned out that her cousin was alive, with whom she would be able to see.

page243

Baba Manya asked to be buried in her son's grave, put Levi's letters in the coffin and put her a picture of her and Lyova. In the hustle and bustle of the funeral I forgot to put the letters with her. They were left in her room and I found them, when I was going through Baba Manina's things. Now I'm glad I forgot. From the letters I learned what and who my cousin Lyova was. I didn't get a picture of him for the memorial until 29 years later.

page244

Ivan Vasilyevich Boyev

I've only seen Uncle John once, and I remember it vaguely. My mother and I went to Zagorsk to visit him. All I remember is the word "sausage," As he called me affectionately for always asking for sausage. My mother brought it for him from Moscow, a product that was unavailable in the village. At that time he was already very ill. On 19 November 1955, at the age of 40, he died. The death certificate states the cause of death as tuberculosis and gastric cancer with metastases. Ivan was born in 1915 in the village of Zabolotye.

The family inventory of belongings, made in 1930 at the time of his father's arrest, includes a harmonica. Obviously, it was bought for his son. According to the memories of his relatives, Ivan was very good at playing the harmonica. His musical abilities were also developed by one of his sons, Vadim, who became a music teacher in Toropetrov. When his father was arrested again in 1937, Ivan was already 22 years old and was not counted among the members of his family. From the estate records of 1940, he had married Praskovya Feodotova, 13 years his senior, with her daughter Anna, born in 1926. Ivan and Praskovya were not farmers, but workers. The family worked in forestry, but there is no record of where they worked. Most likely he was a plotholder, baker, like his father, working as a hired labourer. They had no household. Apparently the marriage was not registered, they had no children. They separated in June 1940, the estate book says that he went to Moscow, but is it really true that he did?

page245

He had another family: his wife Taisia Lukinichna and sons Viktor and Igor. Igor was born in September 1941, after the war had already started. Where they lived is unknown, most likely in the same area, but in a different village. There are no Ivan and Taisia Boikovs in the Zabolotye farmstead registers, but a summons to the army in January 1941 came for him from the Leninskoye

That was the name of Andreapolsky District Military Registration and Enlistment Office till 1965. Ivan was enlisted as a private in the 1241 Rifle Regiment. With this regiment he participated in liberation of his native Kalinin region, fought in Ukraine, took part in forced crossing of Dnepr.

In January, 1944 his fighting army life came to an end. Ivan was arrested and sentenced on January 19 under Article 197.7 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR and the Law of 07.08.1932. Article 197.7 dealt with the AWOL of enlisted men and junior enlisted men. Ivan was subject to item "d", the most severe - absence without leave for more than a day, which was qualified as desertion and was punished by imprisonment from 5 to 10 years, and in wartime - execution with confiscation of property.

The law of 07.08.1932 was known as the "Law of Three Spikelets". In fact, it was not a law, but a Resolution of the CEC and the CPC of the USSR "On the Protection of Property of State Enterprises, Collective Farms and Cooperatives and Strengthening of Public (Socialist) Property". The decree stipulated imprisonment for not less than 10 years and, under aggravating circumstances, execution of the perpetrator. What Ivan's crime consisted of is unknown. He was sentenced to 10 years in labour camps. Given the likelihood of capital punishment, he got off lightly.

A shabby piece of paper from Ivan's camp life has survived - a pass written out in the name of the employee of camp station no. 7, tseytnik Ivan Vasilievich Boikov, which gave

page246

The right of entry to all construction sites from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. until December 31, 1952. On the triangular stamp could be read "Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR - Directorate of the ...russian Railway Construction. In other words, already in 1952, Uncle Vanya was released on parole from prison and worked in the camp as a foreman. Parole was granted for special work distinctions.

At that time Ivan met Antonina Utkina while building a railway near Salekhard and the Obskaya station. Antonina was a native of the Zagorsky district of the Moscow region and had been working in the North temporarily on recruitment. In 1952, Ivan and Antonina returned to the Zagorsk District and settled in the village of Semenkovo. In 1953 they had a daughter Lyudmila. The marriage was not registered and, according to the laws of the time, the father's name was not included on the daughter's birth certificate.

page247

Life seemed to be going well, but Ivan's health was damaged. The front, the camp, the work in the North were not in vain. A letter from Ivan, addressed to my parents and me, aged five, was preserved. It was written a year before he died, on March 14, 1955, while he was living with his sister Vera in Kouchelino. He had just come out of hospital, was feeling a little better, had almost no more pain, but continued to lose weight. Vera was doing well, but he was missing his village and was going home at the end of March.

There was no food in the village, so Vanya asked Mary for three dozen eggs, and 6 kilos of oatmeal. He died on 19 November at home.

page248

Vera Vasilievna Lebedeva

Vera was born on 25 September 1919. After graduating from the seventh grade in Andreapol in 1934, she left for Minsk and enrolled in a six-month course of the Gostrudeskassa.We can only guess how a 15-year-old girl from the countryside got to Belarus 600 km away from home. She probably wanted to get away from home, to see new places. Most likely, her sister Marusya, who lived in Bobruisk at the time After she finished her course, she found herself a job in Bobruisk and was employed as a controller in the postal service.

In May 1936, Vera returned to Andarépol. She was not yet 17 when she was hired as an assistant bookkeeper at the Red October factory. In one year Vera was the assistant bookkeeper at the plant, and the next year she was the senior bookkeeper at the district office. It was a demanding job involving money. She had to work very hard to be trusted, as she was the daughter of a kulak, and in 1937 her father was sentenced for 10 years for concentration revolutionary activities. That year Vera joined the Communist Party.

In 1938 Vera married Sergei Karabashov and on 4 May 1939 gave birth to a son, Valery, which was the name many people used for their sons back then, in honour of a trainee named Khkakalov. According to the records, Vera and Sergiy's family life was short for reasons beyond their control. In the certificate issued by Leninsky.

page249

In an interview with a family member on 23 August 1941, Serey was registered with the Local Branch of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs in Lenin, On 1 October 1939 he was drafted into the army by mobilisation and assigned to the unit as a private, but it does which unit. It turns out that a year after marriage and 5 months after the birth of his son, Sergei never returned home. When war broke out, his relatives had no news of him, and most likely the certificate was issued at their request. Another certificate from the Office of the Record of Absentee and Missing Personnel records shows the date of enlistment in 1942 and the place of enlistment in Leningrad. It also states that in February 1944, Sergey Ivanovich Karbashev disappeared without a trace. According to the family story, Sergey was killed in a train hit by a bomb on the way to the front . It's possible that's what happened. In the early months of the war there was no record kept of the personnel of the retreating army. When recovering each lost or missing soldier, mistakes were unavoidable. The Leningrad region may have become a part of the army. If Sergei had fought in February 1944, his participation in the fighting would have been documented. But there are none.

page250

After her son was born, Vera went to work as an accountant at a food processing company (which one is not disclosed in the employment booklet). Valerik was probably at his grandmother's house in Zabolotye. When the war began, Andreapol very quickly became a front-line town. From September 1 to October 7, the area was occupied partially, then completely to January 16, 1942 In September 1941, Vera went to the village to her mother and began to help the guerrillas. She received a certificate dated January, 18, 1942, from the town Soviet of the Leninskiy district of the Leninskiy district. There survived the certificate issued to her on January 18, 1942, by the town Soviet of the Leninskiy district, signed by the commander of the Partisan detachment, M.I. Kruglov, which informed that V.V. Karbasheva went to the Karbasheva on the instructions of commanders to reconnaissance the location of German troops. The certificate of reward describes her help to partisans in detail: "she went to the district centre to establish the location of German stores, the number of military units and the movement of trains, and helped the unit with food from her farm". Needless to say, how dangerous it was. Any assistance to partisans was punishable by death. Aunt Vera told how the Germans arrested her once. She was saved by chance. During interrogation a local old man came into the house, he was asked if he knew the detained girl. He replied

"What kind of a partisan is she, her father was dispossessed and is imprisoned as an enemy of the people,"Vera was released.

Shortly after the liberation of the Andreapol district in March 1942, Vera and her son moved to the village of Turginovo. This was probably due to marriage. She met Pyotr Lavrovich Lebedev in a partisan detachment. Lavrych, as he was called by all his relatives, adopted Valera. Only many years after his stepfather's death did Valera learn that he was not his real father. Lavrych worked in the district police department, and

page251

Valera and Misha, Kushalino, 19xx.

Vera got a job at a village catering office as an accountant, and in November 1943 she joined the District Consumer's Union as a chief accountant. In September 1943 she became a candidate member of the CPSU, and in October 1944 she was accepted as a Party member. At the end of 1945, after the death of her father, Vasily Panfilovich, her mother, Maria Yegorovna, moved in with Vera from Zabolotye. In 1946 all family moved to Udomlya, where Vera is an accountant. Two years later they moved to Bologoye, and from 1949 to 1956 lived in Kushalino. Moves were probably connected with Lavrych's transfers from one job to another. Vera, with her experience as an accountant and her party affiliation, found work easily in new places.

page252

In Bologom, she was head of the planning department of the timber processing plant; in Kushalino, she was chief accountant and later head of the district procurement office of Rosglavmoloko and Gormolzavod. From that time, for almost forty years until her retirement, Vera worked in the dairy industry. They lived well. In a letter dated March 14, 1955 her brother Ivan, who was visiting his sister in Kushalino, wrote to her sister Nina in Moscow that Vera bought a gold watch and a TV set. Televisions were a rarity in Moscow in those years, not so much in the village. Buying a gold watch was also rare.

Valera was finishing the 10th grade and was dreaming of becoming a geologist when Lavrych died suddenly. It happened in a dream and made such a strong impression on his son that his plans for the future were radically changed. Valera decided he wanted to become a doctor. In 1956 he enrolled at the second Moscow State Medical Institute. N.I. Pirogov. He lived with us in Glazovsky Lane for the first time. On September 1, my brother accompanied me, along with my parents, to my first class. And for him student life began. After her husband died and her son left, Vera moved to Kalinin. She was appointed director of the main dairy in Negotinsky and a year later took over as head of the main dairy in Kalinin. In this position she worked for about 30 years. Vera was given accommodation on Zoya Konoplyannikova Street on the outskirts of the city in a small wooden house, half of which was occupied by the office where Vera worked as director.

page253

Vera was only 37 and did not stay alone for long. Her new husband was Alexei Antonovich Ivanov, who was seven years younger than her. They met on the highway near Kalinin, when Ivanov, an officer on duty at the traffic police station GAI , stopped the car in which Vera was traveling to the district to the dairy plants. Vera often had to drive along this route, and every time Alexei was on duty, she was stopped there.

In the summer, the whole family gathered at the house on Kononoplyanynikov Street. My aunt Chura came from Leningrad with her children Misha and Ira, and from Moscow with my children Marusa and Nina. Aunt Yura did not work and usually stayed with the children all summer. Vatera came, first alone, then with his wife Natasha. I can't imagine how we all stayed in the house, but I remember it was crazy and fun.

page254

Life in Tver was not much different from village life. The wide, unpaved street faced a small cemetery, beyond which the town ended. We children would ride our bikes, go to the meadow to get grass for the rabbits Aunt Vera kept. Nearby was the Tvertsa, where we went for a swim. Sometime between 1970 and 1971 Vera and Alexei were given an apartment to live in. Now my kinfolk used to gather in the summer in the village of Borki.

There were more of us, nephews grew up, started families, brought their own children. The Boykova sisters became grandmothers and looked after their grandchildren. Aunt Vera made arrangements with the chairman of the collective farm, who knew us, that we would be allowed to live in the former manor house. It was very dilapidated, in the autumn the workers who were brought from the city to pick potatoes and other vegetables used to live there. The house stood on the high bank of the Volga at the edge of the village. The windows had a view of the Volga. We washed the huge veranda,

page255

Nina, Vera, Valery, Maria, Sergei and Masha Lebedev, 1987.

Auntie Vera was still working, but often came to visit us in the company car. The sisters would say: "The headmistress is coming. She had worked in that position for a long time and had developed a superior stature and habits. The sisters and Uncle Lyosha laughed about it. Using her position of authority and connections, she helped many people, some to move from the village to the city, some to get jobs. And there were always people around her ready to help her. In 1988 she retired, but she could never sit idle. She was involved in the organization of the veterans' movement in the region, was elected a member of the Presidium of the Tver City Council of Veterans, was the chairman of the Veterans' Trade Service Standing Committee.

page256

Aunt Vera had to bury her third husband too. Alexei Antoninovitch was diagnosed and soon died. Problems started for my son. In Soviet times it was not customary to pay doctors for their services, but there was and still is a tradition of thanking them. He was a doctor of God, and there were many grateful parents. Cognac was the usual gift. He was addicted to alcohol, and the more he got, the more he drank. Divorced, married again, divorced again, married again. Valera, the only son who was Aunt Vera's joy and pride, became her pain. They lived in different cities, she in Tver, he in Moscow, and she was not immediately aware of the danger of what was happening. Her love for her son obscured her eyes, preventing her from seeing the hard truth. Aunt Vera blamed wives, girlfriends, friends, colleagues, but not her son. In 1995, Valera was discharged for health reasons. In his later years, quite ill, he lived in Tver with his mother. He died on 20 July 2001.He was only 62 years old.

Vera Vasilyevna was a strong person. Life went on. There were grandchildren, children, friends. As a veteran she was invited to various celebrations. What I admired about Aunt Vera was that she remained a woman and continued to attract men. Her inner energy, her charm, her affability, her kindness. . One day I found her in her bathrobe, unclothed, with droopy eyes. We were going to go to the cemetery, but she felt uneasy and doubted she could do it. Suddenly a friend of hers called and said he was coming to pick us up in his car. Aunt Vera transformed herself at once, and when Ivan Ivanovich arrived she was there in full order.

Aunt Vera died in February 2004. She was buried next to her son in a nearby Pertizian cemetery outside of Tiberias.

page257

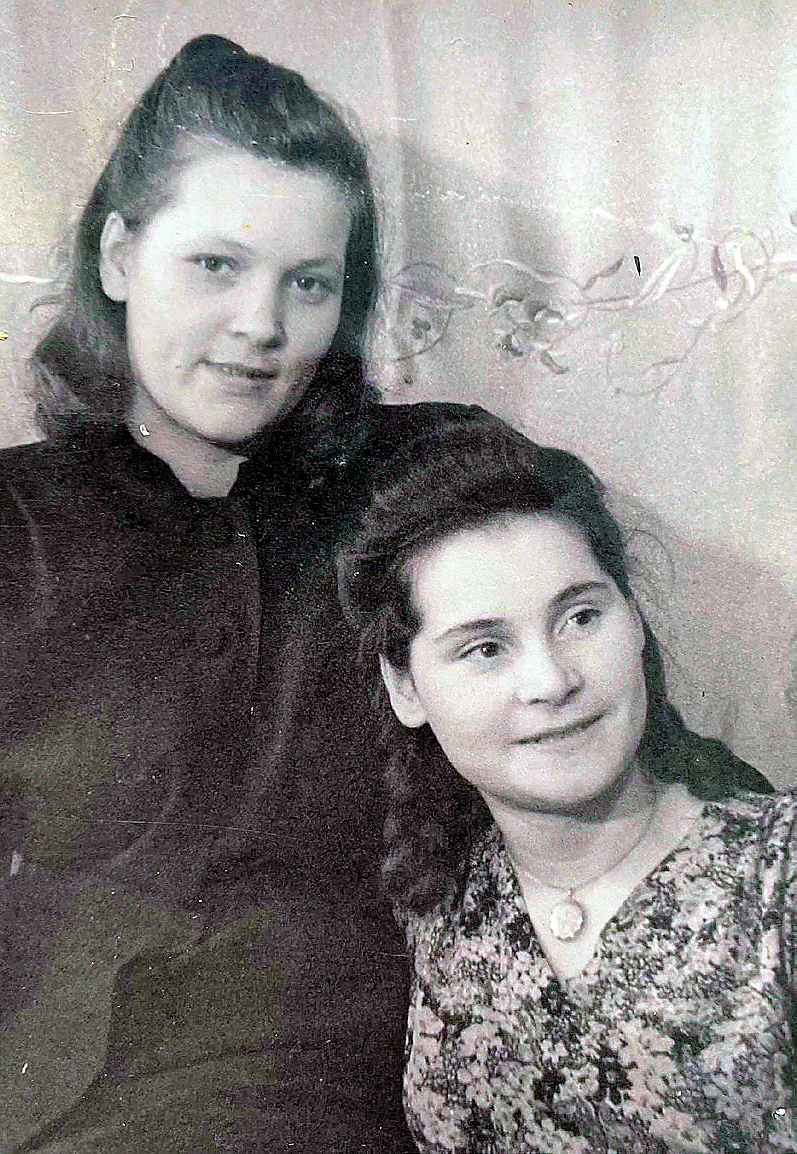

Alexandra Vasilyevna Ivkovova

Shura, the only blue-eyed blonde of the sisters, probably the funniest of them all, was born on 6 May 1922. She was only 8 years old when her father was arrested and Shura's older sister Maria took her in. Marusa's son Lyova was four years younger than Shura. They were like brother and sister, friends, quarrelled, joked with each other. In letters from the school and from the front. Lyov often refers to her. Shura and Marusya's family moved from town to town where Marusya's husband, Alexei, was taken to serve in the city. In 1938 Alexei enrols in the Red Army's Military Academy of Mechanization and Motorization and the whole family moved to the capital. Shura finished school and got a job to work at the Academy as a technician. That's where she met cadet Igor Ivkov with whom she would later marry. In October 1941, during the German offensive against Moscow, the Academy and the families of its staff were evacuated to Tashkent. They returned to Moscow in August 1943.

page258

In 1944 Shura married Igor. After graduation he started work at the Academy. The young family was given a room in the Academy's dormitory and their son Misha was born here on December 20, 1944. In 1947 Igor was appointed to the Leningrad Military Institute of Physical Culture and Sport that had just been created. It was a great success for him. He was returning to his hometown, where his mother and other relatives lived. He continued to do what he loved - motorcycling. Only now he was teaching, and his sporting career had to end. They settled in a large communal flat in Kanonerskaya Street, which before the revolution belonged to the family of his mother, Nadezhda Aleksandrovna Ivkova, née Kovanko. Igor's sister Elizabeth and her husband, an elderly woman, lived in the same flat as his mother.

page259

Nadezhda Aleksandrovna's nanny, Baba Sasha, and other neighbours. On 14 July 1951, Ira was born to Shura and Igor. Soon they received new accommodation on Karl Marx Street. It was an unusual flat, which could be called semi-detached. You enter from the staircase and find yourself in a wide corridor with windows, turned into a communal kitchen. From the kitchen doors led to the rooms. Shura and Igor had a huge room, about 40-50 metres long, with high ceilings and large windows, and two small dark rooms without windows or doors. One of the rooms was a passageway to a large bathroom with a toilet.

I spent almost every summer holiday with Aunt Shura as a child. My mother worked and gave me a lift to her non-working sister. Sometimes we rented a dacha near Leningrad or Moscow, but most often we spent the summer at Aunt Vera's, in Kushalino or Kalinin. It was freeing for us children. As a child, Auntie Shura seemed strict to me, but now I understand how difficult it was for her to cope with three children

page260

in this wooden house without any facilities, she made pancakes, a favourite of ours, thin and small. She had to divide the pancakes in three for us, otherwise it could come to a fight.

Shura devoted her whole life to her family and children. She was a wonderful hostess and it was always a joy to come to their hospitable home. The train arrived early in the morning, Uncle Igor usually met us in his "Pobeda", and on the way we were sure to greet Peter the Great, passing by the monument. At home, a beautifully set table with pies was waiting for us.

The children grew up, Misha graduated from school and entered the Military Academy of Communications, while Ira was already in high school. Aunt Shura was fed up with staying at home and got a job, first as a cashier in a cinema, then in the housing department of the Lesgaft Academy. She did not work long. Misha got married and In 1969 he and Luba had Igor. Aunt Shura became a loving and devoted grandmother.

When Igor was two years old, he was brought to Moscow for a consultation at the Filatov Hospital, where Valera Lebedev worked. Aunt Shura and Igor lived with us in Moscow for a while. Igor was very funny and started talking early. I volunteered to walk with him. I took a book to read to him, figuring that the child would play in the sandbox on his own. I was sitting on a bench, with a book in my hand, and Igor was quietly doing something of his own. We do not disturb each other. Suddenly Aunt Shura comes running in. Her heart felt that I am no babysitter. Indeed, it turned out that Igor was crawling around the bench and picking up cigarette butts. Auntie Shura remembered this story for a long time. In 1974 Ira got married and soon there was another grandson - Misha. Trouble increased. Ira's husband Volodya worked as mate on a long-distance voyage and could be at sea for several months.

page261

We all lived together, which proved difficult. We had to split the flat into two. Misha grew up as a sickly boy, Auntie Shura went to help Ira almost every day, bringing groceries and cooking. In 1988 Uncle Igor passed away. The family became orphaned, life became harder. Uncle Igor worked at the Academy until his last days and received a military pension. After his death, the only regular income of the family was Aunt Shura's pension, which she received for her husband. Ira occasionally worked at the school as a maths teacher, but Misha was often ill and she babysat for him. Auntie Shura's relationship with her son-in-law did not work out, which eventually led to a divorce.

In the early 1990s Ira tried to go into business. High incomes loomed. There was talk of a trip to Paris, property sales in Spain. Sixteen-year-old Misha, who had not finished school, was handing out business cards,

page262

which said in French that he was an agent for a firm. The euphoria was short-lived. One of the big deals fell through, the firm went bankrupt, and the debts were pinned on Ira. She was threatened and forced to sell her flat to pay it off. She and her son and Auntie Shura were relocated to a flat, which was supposedly bought in her name, but turned out to be rented. Two months later they were thrown out on the street. It is hard to write about the last years of Aunt Shura's life. Ira and Misha did not work, lived on her pension and were sinking ever lower. My brother Misha and his wife Lyuba bought them a room in a shared flat, brought them food and clothes, tried to help with their work. But they never returned to normal life. Auntie Shura refused to move in with her son and lived with her daughter and grandson until her last days. She died in autumn 1999. She is buried in St. Petersburg next to her husband.

page263

Dadykins. Daddy's brothers

It so happened that after my grandmother's death my father had a quarrel with his brothers, and they did not see each other for many years. They reconciled when Dad got sick. I met Uncle Vanya and Uncle Seva in the hospital where Dad was hospitalised. One day, when Dad was no longer there, I met Uncle Vanya and Tatiana Borisovna, his wife, at the Vvedenski cemetery, where Grandma was buried. Uncle was very affectionate with me, inviting me to visit. I wanted to go, but I never did. I regretted it very much.

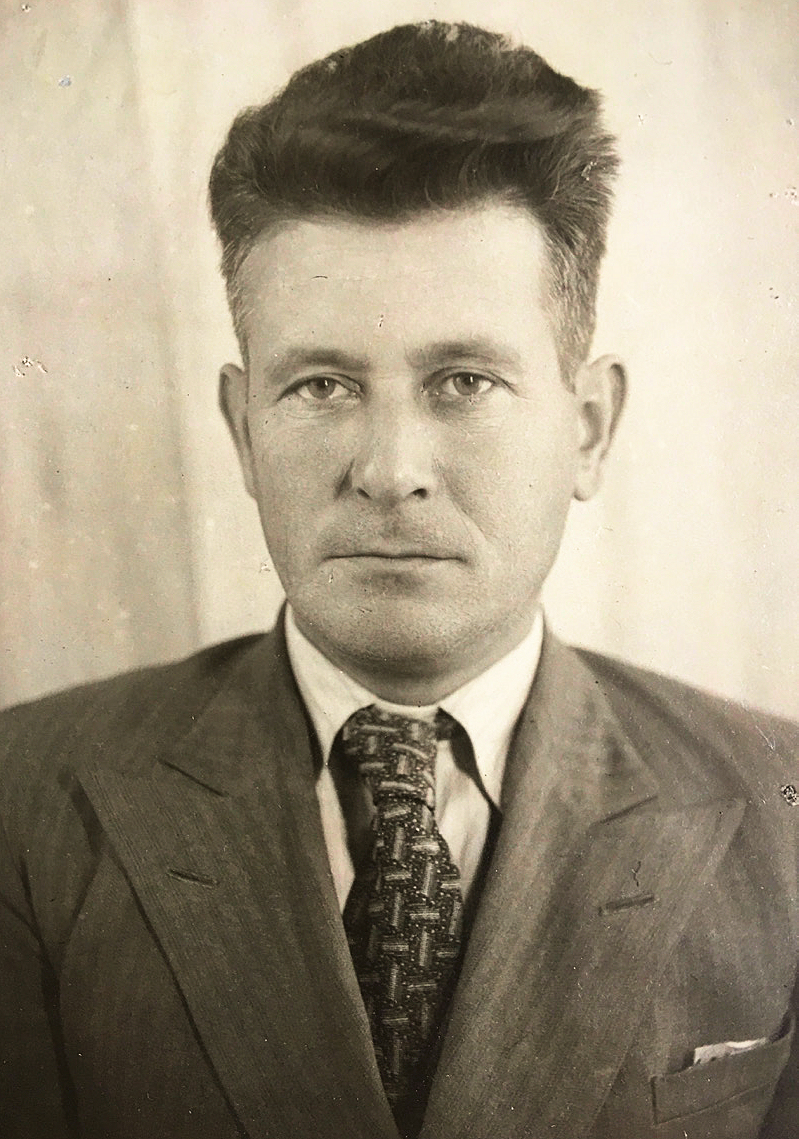

Ivan Petrovich Dadykin.

My father's elder brother Ivan was born in Revel on October 2, 1908, and studied at Lomonosov Grammar School in Arkhangelsk, where his father taught him. He studied well, and in 1919 was promoted to second class with a second-class award. He had to finish school in Moscow, where the family moved in 1921. After completing his studies he entered a technical college, then an institute specialising in electrical engineering. He was an athletic, slim attractive young man, keen on cycling. One day, in 1931 or 1932, he cycled to the Crimea. And that journey decided his fate. In Yalta he met the tanned and beautiful swimmer Lina and took her with him. For a while,

page264

they lived in Efremov, a small town in the south of the Tula region. Ivan was sent there for the construction and commissioning of a power station. Here, on 22 January 1934, their son Leonid was born.

Back in Moscow the young family settled in a communal flat not far from their parents. The baby was sent to the Crimea to stay with Lina's parents. Family life did not work out. Both gave each other reasons to be jealous. Vanya often visited his parents and was even going to move in with them. In 1936 Vanya and Lina separated. Vanya rented a flat for Lina, and Peter Osipovich arranged for her to work as a bookkeeper in the factory. Glafira Ivanovna was very worried about her son and wrote to Seva in 1936:

"I'm glad it's not happening in front of me, otherwise I'm tired of worrying about everything for everyone... Vanya is still alone. I do not know whether he will marry or not.But the family survived. They were united by a joyful event - a daughter, Olga, was born on April 9, 1937.

page265

In the early summer of 1941 Lina and the children went on holiday to Yalta. Ivan was against the trip, as the situation in the world was tense, smelling of war. His fears were not unfounded. Not four months into the war, Crimea was occupied. Contact with his family was lost. As Olga recalled, it was a miracle they had survived. Ivan was at the front, and when the Germans came, a neighbour reported that a Soviet army officer's family was living there. Fortunately Lina learned of the denunciation and managed to escape from Yalta at night with her children. Four-year-old Olya remembered that night's escape for the rest of her life. Fate took them to the steppe Crimea, to the former German villages of Reiter and Totmann. Here they spent the occupation. It was not until early May 1944, when the Crimea was liberated, that a postcard arrived from Lina to their Moscow address. Lina wrote that they were living on the collective farm and that the children were healthy. Ivan was at the front and a flatmate took the postcard to Granny in Glazovsky Lane. One can imagine how happy the grandmother was after almost three years of uncertainty to find out that Lina and the children were all right. She immediately wrote Lina a postcard and gave her address to Vanya, Seva and Rostik. As soon as Ivan had

page266

the opportunity, he went to see his family. Olya did not immediately recognise her father. She remembered him as a young man with beautiful hair, but he arrived completely grey.

After the war and his demobilisation, Ivan went to work for the Ministry of Food Industry, and later worked in the enterprises of that Ministry. As the children grew up, Ivan and Lina separated. Ivan soon married Tatyana Borisovna Gavrilenko, whom he met at work. She was much younger than him and they had no children. Ivan died on August 28, 1981 of a stroke. He is buried in Nikolo-Arkhangelsk cemetery.

Reminiscences of Olga Ivanovna Demitrovich, daughter of Ivan Petrovich

"The end of the war caught us in the village of Totmann. We lived in a real clay mazanka, occasionally refreshing the floor with water and wet rags. There were lots of snakes around, but as I remember, no one was hurt. The stove was heated with brushwood and animal dung. They were dried cow cakes and we hunted for them like mushrooms. There I went to school, which was organized in the surviving building of the club. We wrote on notebooks made from newspapers. My mother's sister, Antonina Kirillovna, who was a teacher by training, was the teacher. When the white acacia trees were in bloom, my brother Leonya and I used to eat their bunches. When I grew up, I tasted it - no flavour, and it tasted awful at the time. When the war ended, we moved to Simferopol and then to Moscow.

We settled in a communal flat in Durnovsky Lane. It was a one-storey annexe, with five stone steps.

page267

There was no central heating, the kitchen was heated with a stove, the toilet was cold, and cooking was done in the communal kitchen on a gas stove, one for three families. We had one room for four people. Dad often went to Grandma's house at that time, not because of bad attitudes, but because of the terrible cramped conditions. Then Leon left by assignment and there were only three of us. Despite the cramped conditions, my mother managed to make our room comfortable and arrange it so that everyone had enough room. We even had an Adler motorbike in the basement, which my dad had brought with him as a licensed trophy from Germany. I remember the first time I met my grandmother. She was very happy, but she was saddened by the fact that her hopes for Pavalik's return were ended. having survived the war, he was lost on the way home. He was carrying some kind of food, which in those days was probably of great value, he was presumably thrown off the train. We searched for him in hospitals and even psychiatric clinics, as some strangeness was noted in his letters. Pavalik's demise had put grandfather on edge and he died.

page268

My brother and I went to school In Moscow, Leonid to boys' school, I think it was no. 69, and I went to school no. 71 for girls, where our grandmother worked as a German teacher. She had retired the year before I arrived, but right up until my graduation the teachers remembered her as an extraordinary person and teacher. She never raised her voice, never judged or scolded anyone, and at the same time had such influence, such charisma (as they say nowadays), that it was impossible to disobey her. We, the grandchildren, my brother Leonid and I, referred to my grandmother only as "you".

My brother, unfortunately, studied poorly, skipping classes and not doing his homework. Dad had to do his homework with him and explain what he, could not and did not really want to learn at school. They would sit at the dining room table, and I would do my homework next to him, so I knew the curriculum for two classes ahead of him. As soon as my father closed his eyes and dozed off, my beloved brother would be away and run to his friends in the yard. The only thing that saved him was my grandmother. She was the only person he dared not disobey. For particularly important tasks, he would be sent to his grandmother's house. He was afraid to lift a finger, let alone run away.

Unfortunately, my brother's life didn't turn out well. All my father's efforts to help him finish ten years of school were unsuccessful. After the seventh form, he enrolled in a technical college, where he studied oxygen and welding. After graduation my brother was sent to work in a closed area far away from Moscow. There he had access to alcohol, from the loneliness and away from loved ones he became addicted to alcohol. Before he reached the age of 60 he passed away. But back to our childhood. Our first school year in Moscow ended early for us. On 19 May 1946 my mother and brother and I flew to Germany to visit my father. He was working as an airfield dismantling engineer.

page269

We spent a summer in Germany in a small village near the Baltic Sea. And here a story happened, so unusual that I will tell it separately. Mum went away for a few days. We kids, led by my brother - I was 9 years old, my brother was 12, the others were somewhere between 8 and 10, mostly girls - decided to explore the pier in the little harbour, where there were many boats and motorboats tied up. I walked up to the very sdge, to measure the depth with a stick, and of course slipped into the water. The depth was much deeper than my stick. None of the adults were around, my brother had stepped aside, and the other children came to the edge and staring at me in horror. I couldn't swim, but there was no fear. The water was already lapping at me and I had time to say goodbye to my mother, father and Comrade Stalin (it really was). Then my brother saw what was happening, ran to the edge of the pier and held out his hand to me, but I kept getting carried further away. By some miracle, my brother saw a long pole on the bank (apparently, it was used to push the boat from the shore), handed it to me, I grabbed it and he pulled me out. Dad and Irma were running to the shore with a blanket. They put me to bed and for two days I felt like a princess. The discharge came later. Everyone went for a boat ride and as soon as I felt the water under the boat, I was hysterical. I remember every detail of that story. What if there had been no pole?

Daddy really wanted his daughter to skate. But where to get them? They weren't on the market. Here's what he came up with: he bought some good leather shoes somewhere (there were no synthetic ones yet) with spikes on the soles, apparently for running. He bought some hockey skates, the simplest ones, called "eiderdowns," and had them screwed onto the shoes. They were my first skates, and I first skated on a frozen piece of asphalt in the yard.

Usually in the summer the sons sent grandmother, to the dacha . None of them had their own dacha, so they rented it. It was mostly paid for by Uncle Seva. He was successful quite early on, holding high-paying positions and helping out regularly with the finances.

page270

. One summer my grandmother lived in a cottage with us. I was about 15 or 16 years old. It was a group of people: my mother, my cousin from Krymma, my brother Leonid, me, and of course my grandmother. She quickly became well known among the locals for her unconventional routine and fixed daily schedule. While everyone was asleep, Grandmother went to the river for a swim, then a morning walk and then breakfast.

That time when we were living at the cottage, my brother had to go to a military training camp. As a technical school student, he was exempted from military service during the training period. It was decided to organise a holiday camp on the occasion of the holidays. We all thought we were taking him somewhere far away for a long time. We bought a lot of local food and two young chickens. There was no fridge and the chickens, or rather the poultry, were bought alive. One we ate at the party table. Who took on the role of bailer, I can't say, but it was probably our hostess, and the other stayed on to live. He was mostly fed by grandmother. The chicken grew up, never left grandmother's side, and accompanied her on her daily walks. Grandmother liked to walk a long distance in the evening, the lane was a well-trodden path, which was very comfortable for her unmistakable companion, a cockerel that had grown up towards the end of summer. In the village they used to say: "We've got a madwoman who lives here.

page271

I remember very well our grandmother's walks in the cold weather in her fur coat., and the rooster waddling after her with his chicken-like gait. He would only follow Granny, never us. Uncle Seva visited Grandma at the dacha. One day he brought bananas. We were all given a banana, and it was the first time I had ever tasted one. I thought it was the tastiest thing I'd ever eaten. Now I can confess that I couldn't sleep at night, so I got up and quietly ate another one. Apparently, Uncle Seva had brought quite a lot of them and my "crime" had not been noticed.

Every year on 9 May my grandmother celebrated her birthday. It was her day and all her friends and relatives never forgot it. Grandma didn't invite anyone and didn't appoint any specific time, everyone came when they wanted and when time allowed. The table was already set in the morning, some came for breakfast, some for lunch, and some even spent the whole day at Grandma's, myself I remember at lunch and in the evening at dinner. The sons usually gathered in the evening, they all sat around a large table, with a large bench attached to the table, there was enough space for everyone, and food, albeit modest, was also available. When Uncle Seva was in Moscow, the table was laden with delicacies. I remember my grandmother's soup, very clear, with unusually neatly diced vegetables. My mother found this soup too bland. She was born in Crimea and was used to spices, but I, on the contrary, found the soup very refined, so I still remember it. There was also baking, which Natasha, the domestic helper, was good at. The most important thing I remember is that family gatherings on this day were always very bright and friendly. My grandmother had such a special aura, no one ever quarreled or spoke ill of anyone in front of her. My last birthday during my grandmother's lifetime is particularly memorable for me. My mother, despite having problems

page272

was always throwing parties and having quite a few guests, mostly my school friends. On my eighteenth birthday, my dad and grandma came. My father looked very mysterious and pleased, and my grandmother handed me a shabby box, tied with a rubber band, and in it was my grandmother's most prized piece of jewellery, a diamond brooch in the shape of a lily of the valley sprig. She said: "Just don't pawn it or sell it," and walked into the room where my friends were sitting. Everyone, of course, gasped when they saw my grandmother's gift. Why did Granny say: "Don't pawn it"? Before the war she had given my mother some rings, which my mother took to a pawnshop because she had no money. After the war it was still possible to buy them back, but either my mother did not know, or she had no money, and she was ill. In short, the things disappeared. Why this valuable present was given to me? My grandmother had other granddaughters - Nina, Irina, and Masha. Nina was even older than me. I think there was only one reason - I was the granddaughter of her eldest son. The rest is very hard for me to remember and the guilt still haunts me to this day. But first things first. Very quickly my grandmother's first wish was violated by my mother. The brooch moved to a pawnshop and since then I've only seen it in between redemption and a new pawning. Of course it's terrible that my mum did that, but it's easy to judge, but it's very hard to sit without money, and with children, too. The temptation to get money quickly and easily and to buy groceries is great. That's how I found the way to the hated pawnshop. Then, when I was already married, we moved to a new co-operative flat on Molodezhnaya. I had my favourite brooch and sometimes adorned my hair. I was again terribly short of money, I had debts to pay, and I so wanted to buy new dishes. And then my "friend" comes along and makes me this offer: "Sell the brooch to me, and if you change your mind, you can always have it back".

page273

I finally spent the money I had been dreaming of, skis and something else. Three months later, I was terrified, I called my friend: "Ira! I'm ready to live on water and bread, give me back my BROOCH!" And I hear in reply: "Oh, my mum has it." She did not return the brooch. That story still haunts me to this day. I even believe that all my subsequent troubles and mishaps are because I didn't comply with my grandmother's request. My narrative of my grandmother would be incomplete if I didn't talk about her beloved sons. The youngest Rostislav, everyone called him Rostik, was very handsome, tall, cheerful. Externally, he was somewhat different from the other brothers, looking more like grandfather, while the other three brothers looked like grandmother, especially the older brother Ivan, my dad. Ivan and Vsevolod, Uncle Seva were very friendly with each other.

page274

Vsevolod Petrovich Dadykin

Seva was born on 3 (16) April 1910 in Vilna. His family lived in Pernov at this time, but Glafira Ivanovna went to her parents for the time of his birth. In 1919 he entered the preparatory class of the Arkhangelsk Lomonosov Grammar School, where his father taught. He finished school in Moscow where his family moved in 1921. After completing a seven-year cycle, he studied at Pedagogical Course No. 7 in the Khamovniki District. In the characteristics issued to him at the courses, noted: "The success rate is average. He performed satisfactorily as an intern. General giftedness is above average. Pedagogical also...". This is the time of Seva's first publication, in the magazine "On the way to a new school" (No. 3, March 1927) it was an essay on the practice at the experimental base. Then he studied at the K.A. Timiryazev Academy of Socialist Agriculture , from which he graduated in 1931. In January 1931 he met his future wife Olga at a meeting of future agronomists who were heading for collectivisation at the Timiryazev Academy. In the same year they set off together to work in the Far East at the Rodnichnyi flax farm in Shmanovsky District.

page275

In October 1932 they signed a contract with Gostrest Dalstroy and left to work in Nagaevo Bay (Magadan construction area). Here their daughter Nina was born on 9 June 1934.

After the birth of their daughter Seva and Leleya (Olga) returned to Moscow. They settled with their parents on Glazovsky Lane. The older brother Ivan by this time was already married and living separately. The younger ones, Pavlik and Rostik, had to squeeze in and give up their room to the young family.

In Moscow, Vsevolod joined the Committee of the North at the All-Russian Central Executive Committee as a consultant on northern agriculture. In the capital he did not stay long. Already in the summer of 1935 Vsevolod was sent

page276

to Yakutia as part of the Special Indigirskaya Expedition of the Glavsevmorput, for the first agronomic reconnaissance of the huge, previously unexplored Indigirka River basin. His wife Lelya and little Ninotchka stayed at home with their parents. The steamer Rusanov, on which he was to sail, set sail from Arkhangelsk and he was once again in the city of his childhood. The route of the expedition can be traced by the short messages sent by Vsevolod from the "Rusanov". On the morning of the 18th of July they left Arkhangelsk, and on the 21st of July they anchored in Varnek Bay on the Vaigach, where the icebreaker "Lenin" was anchored. The timber carriers Sakko, Molotov and Peasant Fram approached here. On 25 July the caravan moved on to the Kara Sea. Letters and telegrams were being sent to and from Moscow. They came more or less frequently depending on where the expedition was. Several parental letters have survived. Glafira Ivanovna and Peter Osipovich were worried about their son: "After all, you,

page277

you live in a terrible environment. Especially when I remember the terrible cold and frost, it always makes me sick," Father wrote on 18 June 1936.

A letter dated 7 November 1936, from Galafira Ivanovna

"My dear Sevochka!, where are you? The sorrow grips me when I remember where you are and what it is like to bear the hardships of winter in the Arctic. My daughter-in-law was very happy: "Ninny is a lovely girl, My mother and I love to take care of her. Things are going well with Lelela. She is an ideal mother in every way. It's boring for Lela without you. She's completely disconnected from her personal life and spends all her time with her daughter.

Seva returned from his expedition in 1937, for a few months he worked for the Russian Federation Ministry of Agriculture, and in January 1938, they were in the Polish Republic. Together with Leila, they joined the staff of the European Plant Research Institute, where they researched farming in the Far North and Sub-Arctic. In the 1930s, when the exploration of the Northern Sea Route began, the field gained particular prominence. The base was the Polar Research Station at the Kola Peninsula Institute of Plant Industry. They travelled as a family to the city of Kirawsk in the Marmara region. In early 1941, Vsevolod was awarded his doctorate

page278

He was invited to work at the Institute for Permafrost Research of the USSR Academy of Sciences. His work was interrupted by the war. From 23 September 1941 to 15 July 1946 he was in the army in action: a infantry battalion of the MGVK. In December 1942 at the Kalinin front, Vsevolod was severely wounded in the chest by a shrapnel. This shrapnel stayed in him till the end of his life. In 1944 Major Dadikin was awarded the Order "Red Star". Even more joyful event of the year was the birth of his daughter. Irina was born on April, 9, 1944. In 1945 Vsevolod was awarded with medals for capture of Berlin, for clearing of Warsaw and for a victory over Germany. In July 1946, after his demobilization, he returned to the Institute of Permafrost of the USSR Academy of Sciences, and plunged into his beloved work. After five years of hard work, in 1951 he submitted his doctoral thesis. His monograph "Peculiarities of plant behaviour on cold soils" was awarded the Timiryazev Prize in 1953.

Vsevolod's work involved constant business trips. He taught a special course on plant physiology in the North at the Natural Faculty of the Yakutsk State Pedagogical Institute, and from 1952, he headed the Yakutsk Institute of Plant Biology.

page279

In 1952, he was transferred to the post of the First Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of Yakutsk Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences and from 1953 to 1957 served as Chairman of the Presidium. From 1960 to 1962. Vsevolod worked in Petrozavodsk as Chairman of the Presidium of Karelian Branch of the AS USSR. He was then invited to lead a new line of research in Russia related to space plant breeding.

In Moscow, the organization p/n 3452 (the future Institute for Medical and Biological Problems of the Institute for Biomedical Research) was established, where systematic research on cultivation of higher plants in closed systems began under the leadership of S.P. Korolev as part of the Space Exploration Program. In March 1970, Vsevolod Petrovich started teaching work at the Moscow Forestry Engineering Institute, where he became head of the Department of Botany and Plant Physiology. Here he worked until the last days of his life. He died suddenly on his birthday, April 16, 1976. A shell fragment, which he had been carrying in his heart since the war, dislodged, and his heart stopped. He was 66 years old. He was buried in Moscow at the Khimki cemetery.

page280

Pavel Dadykin

Paval's Diary Pavel was born in Arkhangelsk in 1912, and exactly 30 years later, in 1942, he went missing. Not at the front, but on the home front, on his way from Kaluga to Gorki region, where his parents were evacuated. He didn't have time to marry, didn't leave children behind. I know about Pavlik, as he was always called in the family, thanks to his diary and a few letters that my grandmother and father kept. Thanks to them for that. The diary is two thin notebooks, the first dating from 1930, the second from 1936. Pavlik kept the diary irregularly, according to his mood. Such moods most often occurred when he was feeling lonely and unhappy, so the general tone of the entries is minor. He complained about constant bad luck, about life "playing a cruel joke on him". At times there are even flashes of suicidal thoughts. This is partly due to his age. Pavlik started keeping a diary at the age of 18, an age when people tend to be pessimistic. In reality, it wasn't all bad. He grew up in a close-knit loving family, was educated, specialised. One only has to look at his photographs to see that he was good looking and the girls liked him. The latter finds plenty of evidence in his diary and is confirmed by our housemate in Glazovsky Lane, Lidia Kanevsky, who thought that Pavlik was the handsomest of the brothers. She must have been in love with him.

Another reason for his pessimism was his poor health. He was ill a lot as a child. In documents in the Arkhangelsk archives of the

page281

Lomonosov Grammar School for 1919, I found a record that the mathematics teacher P. O. Rabinowitsch was temporarily absent for 18 days due to the illness of his son. There were four sons, and it was not clear which one of them was seriously ill for a long time. After reading Pavlik's diary I realised that it was him.

Moving to Moscow. Friends. School

He went to school in 1918. The civil war was raging, power was changing hands in Arkhangelsk. With the arrival of the Reds and the establishment of Soviet power new school programmes were introduced and all pupils were left for a second year. Before a few months of schooling had elapsed Pavlik fell ill with scarlet fever and then malaria, with complications of the heart. He missed more than half a year and was forced to stay in second grade for another year.

In the winter of 1921-1922 the family moved to Moscow. For eleven days they travelled by train in a 20-degree frost. The train could barely make it there. When they got off at numerous stops, the snow was sticking to their boots, melting in the wagon. Pavlik was constantly freezing. "We were all ragged," he writes in his diary. - I was wearing four pairs of trousers, of which not a single pair was intact. On my feet were huge felt boots, which were unstitched and 'plank' wet." As a result, he developed rheumatism. Pavlik was often absent from school, so he spent two years not only in the second, but also in the fourth grade. Since his parents were at work and his brothers at school, he, left at home, had to cook for the whole family. The staple food in the early 1920s was frozen potatoes. The ten-year-old Pavlik peeled, cut, fried and boiled them. "Since then I have had a perpetual blister on my hand from the knife," he writes in his diary ten years later. According to him, he "did not see childhood", "as he did not experience the pleasure of running and playing together

page282

with his mates, which all the boys aged 10-14 were doing.

Of course, there is an exaggeration in these words. He saw his childhood, he ran around with his mates and he was no Cinderella in the family. After listing his misfortunes and illnesses, Pavlik writes that in fourth grade he skated decently, that they had "a decent company of children of employees Rukavishnikov orphanage, with whom we were skating on the boulevards and clinging to the tram. The company was of various ages and included boys and girls who lived in Glazovsky Lane in houses 10 and 12. The yard of house №12, where the company usually gathered, was called Grachevsky, because the house once belonged, as Pavlik writes, to Count Grachev, and was built in the shape of the letter "Г ". The boys played robbery-cossacks, hide-and-seek, sang songs, put on plays, and Pavlik took part in it all. In the company at Grachev's Yard in the winter of 1926-27, Pavlik got to know Nikola Nikolaevich. Pavlik met Nina Pavlova, to whom many pages are devoted in his diary, and who was obviously his first love. She did not know how to skate and he happily began to teach her. He was 14 years old. The school boys laughed at him and teased him for his friendship with the girl.

page283

This distinguished them from the "decent company of employees' children", who, though they clung to the tram, recognised that it was possible to be friends with girls. To get rid of the taunts of his classmates, he referred to the girls he knew as his cousins. This was not the case with his younger brother. Pavlik's numerous hobbies were a constant subject of Rostik's taunts.

Gradually the boys grew up, and the backyard parties were replaced by the school ones, but there were few close friends. Pavlik was fond of amateur radio, photography, went to the cinema and theatre. The second year in grade 4 Pavlik joined the Young Pioneers in the club educators Khamovniki district. Initially, everything was interesting to him and he developed a lot of activity: organized in a school cell "Friend of MOPR", was secretary of the detachment, a counselor link. But the work increased every year and he got bored with everything. In the second year of the 4th form and in the 5th form, he was one of the best pupils, especially in physics and mathematics. In Grade 6 he moved into the middle ranks in all subjects except Mathematics, where he remained one of the top performers. When in Grade 6 he was invited to join the Young Communist League, he resigned from the pioneer group.

In Grade 7, he started having problems with his studies. Perhaps the reason was the girls. He was able to do geography and social studies handily. His older brother Seva helped him with Russian, who wrote two home essays for him. In mathematics he felt quite strong, but was careles with his homework and constantly clashed with the teacher. The result was a satisfactory grade ("oud") for the year. The worst thing he did was in German. He received an "F"-grade and was offered to take German in the Fall. Pavlik wanted to "get off as quickly as possible

page284

from the school" and decided he could do it in a week. According to him, the German "gasped, but still agreed to accept credit for the whole year". He studied for eight to ten hours a day, in the morning with a teacher he knew, and in the evening with his mother. When he arrived on the appointed day to take the test, it turned out that the German, Elizaveta Petrovna Rein, was ill, and the test was postponed to a week. Pavlik did not wait for her to recover, but went to his boss Boris Grigorievich and said that he had to leave in 3-4 days, and he needed the certificate of completion of a seven-year school in order to apply for a technical school. Boris Grigorievich wrote a note that the German was passed, and the certificate was given to Pavlik. So the boy was not a plaything in the hands of an evil fate, as he sometimes thought, but had enough self-confidence, persistence, and agility to solve his problems.

Technical School

Pavlik didn't know where he was going to study before he got his certificate, but he was sure he would not stop at a seven-year school. He was interested in electrical and radio engineering, but opted for the Kamenev Technical School of Construction. B. Kamenev, where his father was working at the time, and where Pavlik thought it would be easier to enroll. Industrialization was underway, and competition for technical schools was large. Pavlik applied to the Faculty of Rural Refractory Engineering (later renamed to the Faculty of Rural Industrial Engineering), where there was an insufficient number of applicants and it increased the chances of admission. At a family meeting it was decided that Pavlik would go to Zaporozhye with his father, where PeterOsipovich was put in charge of the excursion base, and would study there for the entrance exams.

page285

On 14 June 1928 he left Moscow by train. Pavel remembered his trip to the Far East. Firstly, he had met a girl he knew in a parallel class who liked him, and secondly, he and his father were at the construction site of Dneprostroy and were caught up in the opening of the first factory canteen in the USSR, which was to serve Dneprostroy workers. Pavel writes that "Dad talked to the head office management " and they were allowed through "as representatives from Moscow". Not only was it a meal, but it also included a sumptuous three-course meal that included chicken broth, chicken under white sauce, ice cream and a bottle of beer. It was their best meal of the entire time they had been in the South Caucasus. It is clear that Peter Osipovich had nothing to do with either Dneprostroy or the factory canteen, but he seemed to be quite personable and able to talk to people.

Five days later Seva arrived in Zaporozhye. Peter Osipovich and his eldest son were busy organizing excursions, while Pavlik was preparing for the entrance exams to the technical college. His father helped him in mathematics, and Seva in physics, chemistry, social studies, and geography. After a month and a half in Zaporozhye he was sent to Golitsyno, Moscow, to study Russian language and literature with Seva's father. He had to make up for the gaps in his school education.

In the first exam, which was Social Science, Pavlik received an 'fail', but he explained it as an accident: a boy from the village school answered before him, answered weakly, and the teacher mistakenly put his mark on Pavlik's ticket and did not want to correct it. Since Pavlik describes the course of the exam and his answers to each question in detail, I can draw only one conclusion: there was no mistake. He did well in physics and maths. He received a "wud" (very satisfactory) for his essay on "What is the meaning of the revolutionary holidays," and an "oud" for Russian. He was accepted and began lessons on 1 September 1928. In 1930 at the technical college

page286

An institute was established to which the strongest students were transferred. Pavlik was not one of them. Every summer the students of the technical college were sent for practical training. In 1931 Pavlik had serious problems at his job at a building trust. For the first time during his studies he received several reprimands, including a severe reprimand with a warning to withdraw from work. A bad report on the internship threatened him with expulsion from the technical school. The depressed state Pavlik was in can be seen in a draft letter addressed to one of his colleagues at the trust. She was older than him and, seeing the worries of a nineteen-year-old trainee, decided to talk to him. There were no friends or family around and he was in desperate need of an understanding companion. The letter seemed like a continuation of the conversation, or rather it was a conversation with himself and about himself. At work he felt like an outcast: "I am scolded here and hated to some extent and it is impossible to work in this environment. He wrote that he was ill, "almost disabled", suffering from rheumatism for ten years: "my hands and feet are cold, I often can not walk or write", he wrote about a "home" or "family" troubles, which made him more "dry" and "callous", about the betrayal of a friend, which forced him to withdraw, that often thinks about the purpose of life, but nothing to console them, that life is cruel and dictates their laws, but he can not obey them. Pavlik was at a crossroads, doubted his choice of profession - he did not know whether to return to Moscow to study or go elsewhere. He was tormented by a feeling of his own uselessness. Was the letter sent to the addressee? I don't think so. He was selfish and lonely, he just needed to speak out.

Anyway, the crisis was over, life went on. Pavel graduated from technical school, but finding a job in Moscow was not easy, there were job cuts everywhere. When, after a month and a half of searching for a job, he was invited to work at the Kalacheevsky fur farm, he gladly accepted.

page287

Work. Institute

I worked in my field of specialisation on a building site. Industrialization was taking place and it was not easy to fulfil overestimated, sometimes unrealistic, plans. The amount of work was growing, there was a shortage of materials, the supply of food was reduced, the staff of workers was cut. Pavlik had to be tough, which did not suit his character. He writes in his diary: "Rations and absenteeism are two very unpleasant things, because of them you constantly see workers crying in the office, which works on itself. At present the workers' armory is being reduced for truancy, which means throwing eight families with small children overboard, depriving them of their livelihood and giving them a 'wolf's ticket', i.e. a certificate that says "dismissed for truancy", which they cannot get anywhere with, because there are many unemployed people who do not have such certificates. Such people are simply doomed to perish...".

In 1934 he enrolled at the institute. He studied well, worked hard and made good money. He bought himself a new bicycle. He took after his father. He did not like to spend time in one place - the best leisure for him was travelling. After graduating from the institute in 1938, Pavel was sent to Kaluga, but regarded the city as a temporary home. He left part of his belongings and his personal archive with his parents in Moscow. His girlfriend Zoya stayed in Moscow and wrote less often than he would have liked. I assume that Zoya was the daughter of the Aksenovs, with whom my parents were friends. It is no coincidence that upon arriving in Moscow in August 1941, Pavlik stayed with them in Bolshoy Novinsky Lane for three days. His parents were in Kasimov at the time. Then it turned out that Peter Osipovich came to Moscow on August 16, but the meeting with his son did not take place. Pavlik could have stayed in Moscow, but he did not know that his father was coming.

page288

Missing in action